When Did the Byzantine Empire Fall?

The Eastern faction of the Roman Empire, better known as the Byzantine Empire, far outlived its Western counterpart.

An oddity in medieval history is knowing an exact date. On May 29, 1453, the Byzantine Empire fell to the Ottomans. And just like that, 1,500 years of Roman and Byzantine history ended. The end did not come suddenly but only after a long decline, lasting years, often mixed with civil wars and external pressure. Long before the Empire’s rise, Byzantium the city was founded in the 7th century BC. Sitting astride the Bosphorus Strait, Byzantium controlled the only entrance to the Black Sea. This strategic location was gold as the city later would be the economic powerhouse for centuries derived from key Asian and European trade routes.

From City to Capital

Map of Byzantine Constantinople. Source: History.com

Location played a key role in 330 CE. The Roman Emperor Constantine I saw Byzantium’s trading, strategic, and political advantages. In 330, it became the official Roman capital. Rome fell in 476 to Odoacer, a German mercenary who disposed of the last Emperor, leaving only the Eastern Empire. Over several centuries, the changes went beyond politics. The Empire made Christianity the official religion, and Greek replaced Latin. And the Empire prospered during this continuation and change.

The next several hundred years also saw many events that affected the Empire. The Arabs stormed in from the Arabian Peninsula, conquering Egypt in 640. Various Germanic western kingdoms rose and fell, most tangling with Byzantine forces—other threats, like the Sassanid Empire and Seljuk Turks came from the East. Before 1000, the Empire reached its maximum size, from Spain to the west to the Middle East. But the constant wars never ceased. Internal strife took its toll, too. Now trouble brewed, coming from the East. Enter the Seljuk Turks, aimed at Anatolia, the heart of the Empire.

A Crucial Battle and Waning

The ill-fated Battle of Manzikert. Source: Daily Sabah.

The disastrous Battle of Manzikert in 1071 displayed the cracks in Rome’s successor. The Seljuk Turks defeated a sizeable Byzantine army, forcing the Empire to pay tribute. Large swathes of Anatolia now become Seljuk territory. Manzikert hit the Empire’s territory and psyche. The loss of Anatolia proved devastating to the military, losing their biggest territory to for military recruitment. In the years following this battle, Byzantine historians lamented the Empire’s wane started here. The following decades only proved them right.

That Slippery Slope

Entry of the Crusaders in Constantinople, by Eugene Delacroix, 1840. Source: Historynet.com

The year 1204 saw the Empire take a worse, crueler hit that caused irreparable damage. The large Fourth Crusade, destined for Egypt, pivoted and sacked the capital Constantinople. Fueling this campaign was money and political desires. Constantinople’s fabled wealth made it an irresistible target, and Venice, a trading rival, sought to control the Empire’s trade routes. The surprise attack succeeded, followed by three days of looting and the Empire carved up.

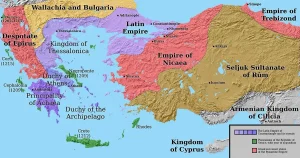

The “Latin Empire” lasted until 1261, when troops from Trebizond retook Constantinople. But the Empire never regained its former glory or domains. Civil wars again weakened imperial power. And its most aggressive threat loomed.

Expansion At the Empire’s Detriment

1204 Byzantine Political Map

The Byzantine Empire’s greatest and final adversary arose in Anatolia – the Ottomans. These Turks proved themselves more capable than the Seljuks. To the Ottoman’s delight, the Mongols wreaked havoc across the Middle East.

The Ottomans expanded, absorbing smaller Muslim states. By 1354, the Ottomans took Byzantine territory, spreading into Europe. Their armies defeated the Serbs at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, cementing their hold. By 1451, the Ottomans surrounded the Empire, leaving slivers. The Empire’s existence became precarious.

The Final Acts

Constantinople’s fortifications Source: Wikimedia Commons

The mid-15th century Byzantine Empire picture was not a rosy one. All attempts at restoration achieved mild results. Besides the inexorable Ottomans, other enemies like the Serbs and Bulgarians conquered Imperial territory. Even the Venetians popped up, taking a Greek city or two. Throw in another civil war, and the Empire looked right for the plucking.

The Empire’s situation went from precarious to dire after 1440. The Ottomans crossed the Bosphorus Straits, conquering as they did, enveloping Constantinople. A two-year siege in 1444 failed, defeated by the Theodosian Walls. In vain, the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos appealed to the West, but little aid came. The Pope wanted control of the Orthodox Church was one reason. Others wanted to scavenge any spoils.

In 1453, the Ottomans under Sultan Mehmed II struck. They used artillery and infantry to breach Constantinople’s mighty walls. The siege lasted for fifty-five days. Constantine XI’s defenders, numbering 7,000, fought but lost. Per tradition, Mehmed allowed three days of looting. On May 29, 1453, Byzantium fell. The Ottoman expansion paused but then revved again, storming further into Europe. Some Byzantine cities resisted, with the last snuffed out by 1461.