When Did People Begin Using Coins, and Why?

Today, coins are taken for granted and sometimes even discarded, but their development played a crucial role in the evolution of ancient economies.

As modern society becomes cashless, coins could, at some point, become obsolete. Yet coins played a vital part in the transition from a barter economy to an economy with a monetary standard, as is the case today. The evolution from barter to coinage took place over thousands of years and across hundreds of miles in the Near East and eastern Mediterranean Basin. Before moving on to examine how this process took place, definitions of some of the key terms are important. The eminent British art historian and contributor to The Cambridge Ancient History, Charles Seltman (1886-1957), defined the process of ancient economies as follows:

“Metal when used to facilitate the exchange of goods is currency; currency when used according to specific weight standards is money; money stamped with a device is coin.”

What Were the Early Currencies? The Egyptian Deben

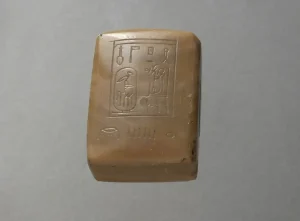

Six Deben Weight, Egyptian, 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom (1550-1425 BCE). Source: Louvre Museum, Paris

The ancient Egyptians played an early and crucial role in the evolution of currency to coinage. Although the Egyptians did not develop a coin currency, they were among the first people in the world to use standardized weights. The standardized weights were used as a medium of exchange and as a pseudo-currency. Beginning about 3100 BCE, the Egyptians used the weight measurement known as the deben as the standard weight. A deben weighed about 93.3 grams and was used to measure the value of metallic goods such as copper, silver, or gold. During the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (c. 1985-1773 BCE), the Egyptian measurement system was further standardized. After that time, the deben could be further divided into a measurement known as a kite, ten of which equaled one deben or about ten grams each. Kites were only used to measure gold and silver. Several Egyptian scales and balances are extant and in museums around the world, and the act of weighing is depicted on the walls of many New Kingdom tombs.

Although these measurements only measured metallic goods, they were eventually used to determine equivalent values of nonmetals. This transition made precious metals the basis of the economy and the deben was the medium of exchange, making it a currency. The deben was still a cumbersome medium of exchange and was far from being coinage, but it worked well for the needs of Egyptians and could even facilitate international trade.

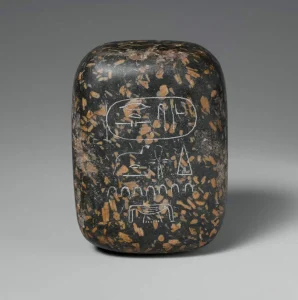

Seventy Deben Weight, Egyptian, 12th or 13th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (1850-1640 BCE). Source: Metropolitan Museum, New York

An interesting text from the reign of Thutmose III (ruled c. 1490-1436 BCE) notes how the Egyptians controlled trade with the Canaanites. The text also indicates how the deben was used to measure silver.

“Behold, these harbors were supplied with everything according to their dues, according to their contract of each year, together with the impost of Lebanon according to their contract of each year with the chiefs of Lebanon__________ 2 unknown [birds]; 4 wild fowl of this country, which [_] every day. . . The tribute of Kheta (Hatti) the Great, in this year: 8 silver rings, making 401 deben; of white precious stone, a great block; wood _____ [returning] to Egypt, at his coming from Naharin, extending the boundaries of Egypt.” [Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt. Vol. 2, The Eighteenth Dynasty, page 2040]

It should be pointed out that the Hittites (Kheta) and the Egyptians were peers in the Great Powers geopolitical system of the Late Bronze Age. The “tribute” mentioned in the text is likely a “gift” that the Great Powers routinely gave each other. Regardless, by the Late Bronze Age, the deben played an important role as a medium of exchange in the Egyptian economy. The deben was also a crucial step in the development of coinage.

The Sumerian Currency

Sumerian Language Cuneiform Silver Account from Umma, Neo-Sumerian, Third Dynasty of Ur (2112-2004 BCE). Source: Louvre Museum, Paris

Hundreds of miles to the east of Egypt in Mesopotamia, the Sumerians developed their own currency and money system at about the same time. A plethora of Sumerian language cuneiform tablets from the city of Umma show that a silver-based accounting system was used in southern Mesopotamia during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112-2004 BC). The tablets indicate that the Mesopotamian economy was highly centralized, although trade was carried out by independent contractors. A comptroller would receive capital goods from the ensi (a governor or regional ruler) and then release the goods to the government sanctioned merchants. As the merchants collected exotic goods from outside Mesopotamia for Mesopotamian goods, they entered the transactions into the ledger using silver as the medium of exchange and value. The use of a silver standard allowed the Ur economy to flourish because merchants were no longer forced to determine transactions on a case-by-case basis.

The silver standard of Mesopotamia can be considered money by Seltman’s definition and was the next crucial step to coinage. The silver accounting system worked well for the needs of the Mesopotamians, but like the deben, it was cumbersome, especially for large transactions. The next major advances in currency, money, and coinage took place between Egypt and Mesopotamia in the region known as the Levant or Syria-Palestine.

The Jump from Money to Coinage

Frog Shaped Weight, Babylonian, 2000-1600 BCE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The evidence shows that there was a gradual transition from currency and money to coinage from the eleventh through the seventh centuries BCE. The shekel was originally a measure of weight, like the deben, used in the Near East but it later became a currency standard and eventually a type of silver coin. In the Old Testament, ten dramas, which were gold coins, equaled one shekel. An early reference to the shekel was in I Samuel 9:8, during the reign of King Saul of Israel in the eleventh century BCE.

“And the servant answered Saul again, and said, ‘Behold, I have here at hand the fourth part of a shekel of silver: that will I give to the man of God, to tell us our way.’”

Beginning in the eighth century BCE, some Near Eastern peoples began minting the first coins with impressions. The Canaanite city-state of Megiddo began minting coins at this time, which was followed by Ephesus in the seventh or sixth century BCE. Not far from Ephesus in Asia Minor (modern Turkey), the Lydians made the official step to coined currency.

The Lydians and the Invention of Coinage

Electrum Vase from Anatolia, Anatolian, 2300-2000 BCE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Lydia was one of several Anatolian kingdoms that emerged after the collapse of the Hittite Empire around 1200 BC. The Lydian people spoke an Indo-European language known as Luwian that was related to Hittite, yet culturally the Lydians were closer to the Greeks. The Lydians became known for their great wealth, which flowed from the Pactolus River down Mount Tmolus. In his Histories, the fifth-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus wrote:

“The country, unlike some others, has few marvels of much consequence for a historian to describe, except the gold dust which is washed down from Tmoulus; it can show, however, the greatest work of human hands in the world, apart from the Egyptian and Babylonian: I mean the tomb of Croesus’ father Alyattes.”

Gold Lydian Coin, Lydian, The Reign of Croesus (560-546 BCE). Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Prospectors used sheepskins to filter the gold, which was actually the natural gold-silver alloy electrum. The electrum was then brought to the Lydian capital city of Sardis, where it was refined into gold and silver and minted into coins. Herodotus claimed that the Lydians were the first people to use coin currency. He wrote: “The Lydians were the first people we know of to use a gold and silver coinage and to introduce retail trade.”

Terracotta Jar and Lydian Gold Coins, Lydian, The Reign of Croesus (560-546 BCE). . Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Lydia’s economic golden age began under King Gyges (ruled 680-652 BCE), although it was Croesus (ruled c. 560s-540s BCE) who benefited most. Croesus used Lydian wealth to make Sardis a center of learning and the envy of the classical world. Due to his efforts, Croesus became known as the richest man in the world, but his wealth was not enough to stop the Achaemenid Persians from conquering his kingdom.

Ancient Coinage after the Lydians — The Persians and the Greeks

Silver Coin of Darius I, Achaemenid Persian, c. 500 BCE (Reign of Darius I). Source: British Museum, London

The idea of coined currency did not die with the Lydian Empire but was inherited by the Persians and Greeks. The Achaemenid Empire, which stretched from Egypt to India, actually facilitated the spread of coinage. During the reigns of the Persian kings Cyrus (ruled 559-530 BCE) and Cambyses (530-522 BCE), the subject people paid their tribute to the Persians in silver. The silver they paid was in talents, which was essentially bullion and difficult for smaller transactions. Under King Darius I (rule 522-486 BCE), the Persians began minting coins, with the gold daric and the silver siglo being the standards. Siglo was the Persian word for shekel. As the Persians adopted coinage for use throughout their empire in the east, the Greeks also began using coin currency in a number of their city-states.

The Greeks began adopting coin currency in about 500 BCE, not long after they were introduced to the concept by the Lydians. The adoption of coinage by the Greeks was uneven, though, owing to the fact that they did not have a single central government. They were first used for local use within city-states before they gradually transitioned to interstate use. A typical Greek silver coin would have a blazon on the front side to identify the city-state, while emblems and other symbols were on the reverse side. Early Greek coins were as much a source of state pride and propaganda used by ambassadors as they were a form of currency.

Silver Coin from Syracuse, Greek, Late Fifth Century BCE. Source: British Museum, London

The period just after the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449 BCE) saw the two leading Greek states, Athens and Sparta, embark on different paths. The Spartans focused most of their attention and resources on being the premier military force in Greece while the Athenians built an economic empire. The Athenians were also leaders of the Delian League, which was political and economic as much as it was a military alliance. In 454 BCE, the Athenian leader, Pericles (495-429 BCE), removed the treasury of the league from Delos to Athens, making Athens an economic superpower. The Athenians then decreed that their allies adopt Athenian weights, measures, and coins, starting an economic war with the other Greek city-states. Athenian attempts to control and monopolize coinage in Greece was a major factor in the destructive Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE).