What distinguishes provincial Rome from imperial Rome?

The differences between imperial Rome and the Roman provinces were vast. Find out what separated the capital of the Roman Empire and its huge numbers of provincial inhabitants.

Oct 7, 2020 • By Laura Hayward, MA Classics, PGCE Classics, BA Latin with Greek

The Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum, 4th century AD, via Colosseum Rome Tickets (left); with The Temple of Aphrodite at Aphrodisias in the Roman Province of Asia, 1st century BC, via Slow Travel Guide (right)

The great imperial era of ancient Rome started with the accession of the first emperor, Emperor Augustus, in 27 BC. This era ended with the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. Throughout this time the boundaries of the Roman Empire expanded and receded. At its height in the 2nd century AD it stretched from the west coast of Africa to ancient Arabia. The city of imperial Rome lay at the center of this vast empire, an empire made up of a large number of Roman provinces. These provinces (provinciae to use the Latin term) were defined as foreign territories under permanent Roman administrative control.

Imperial Rome And The Roman Provinces

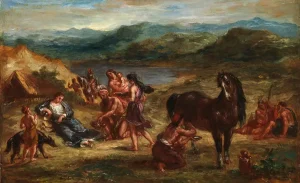

Ovid among the Scythians by Eugène Delacroix, 1862, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

There were many differences between the city of Rome and the Roman provinces in the imperial era. These differences were evident in every aspect of life from the government to religion. One of the main cultural and social differences was that life in the provinces was regarded as far less sophisticated than life in Rome. It was easier for someone to rise through the ranks of Roman society in Rome than in a remote province at the edges of the empire. The Roman poet, Ovid, exiled to Tomis on the Black Sea AD 8–18, wrote many letters bemoaning his new rustic lifestyle hundreds of miles from fashionable Rome. However, it is also important to note that the provinces provided Rome with famous poets, such as Petronius and Apuleius, and even emperors such as Emperor Septimius Severus from Africa.

Roman marble portrait bust of Emperor Septimius Severus, late 2nd century–early 3rd century AD, via Christie’s

Despite their differences, the city of imperial Rome and the provinces were mutually dependent on one another. Rome, the beating heart of the empire, was where all major foreign policy decisions were made. The Roman provinces depended on Rome’s rule for protection from both external and internal threats. In turn, the provinces were vital for spreading Romanization throughout the empire. They also boosted the Roman economy and provided much-needed soldiers for the Roman army. These were all essential elements for the success of imperial Rome.

What Were The Roman Provinces?

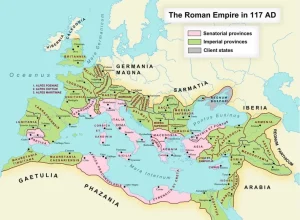

Map of the Roman Empire in the 2nd century AD, via Vox

Roman provinces were usually added to the territory of the Roman Empire after a war between the two sides. A peace treaty was agreed between imperial Rome and the conquered land. In this treaty, settlements were made with regard to land boundaries, taxes and administrative structure. This would then be confirmed by the Senate back in Rome and made into law, known as the lex provinciae.

Each province was then assigned a Roman governor who had complete power (imperium) over the inhabitants of the province. The governor had officials, called quaestors and legates, to assist him. He also had a staff of military and civilian personnel, who were often young men in the early stages of a political career. Family members were also allowed to join the governor if he wished. Some of the most important Roman provinces were: Gaul (modern-day France), Spain, Egypt, Asia, Syria, Britain and Africa.

Government And Administration

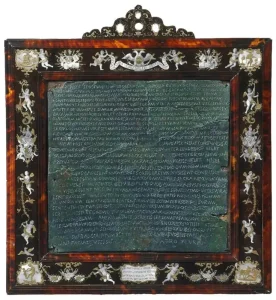

The Senatus Consultum de Bacchanalibus, the oldest senate resolution to have ever been discovered and one that prohibits the celebration of Bacchic rites, 186 BC, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

The form of government for the conqueror and the conquered in the Roman Empire was clearly very different. The city of imperial Rome was home to the seat of executive power, the Roman Senate. The senate was made up of hundreds of senators who made all the important decisions on policy and law. A senatorial resolution had binding force and was known as a Senatus consultum. At the top of the senatorial tree were the consuls. Each year, two consuls were appointed by the emperor as simultaneous leaders of the Senate.

In the imperial era, the emperor held the ultimate power. Although the Senate could vote against him and make his life difficult, the emperor often had the final say in most major political decisions. Emperor Augustus introduced a series of reforms in the late 1st century BC. These aimed to streamline the senatorial process and improve the administration system.

Statue of Emperor Augustus from Prima Porta, 1st century AD, via Musei Vaticani, Vatican City

Administrative control in the Roman provinces was, as we have seen, held by the governor. Even though he was bound by the laws of the Senate he also held a considerable amount of autonomous power over his subjects. There were imperial provinces, which belonged to the emperor but were governed by legates. Senatorial provinces were governed by proconsuls who were appointed by lot annually.

Administration across the provinces was not uniform since some provinces had greater independence than others. These variations also existed within provinces with some territories and local tribes allowed an element of self-government. Client kingdoms were an example of self-rule. These kingdoms were responsible for their own law and order and protecting their frontiers. But they could ask for assistance from imperial Rome in emergencies. The ius Italicum, the right to own and govern one’s own land, was the highest privilege granted to those in the provinces.

Statue of Pliny the Younger from the façade of the Cathedral of Santa Maria Maggiore, Como, Italy, pre-1480, via Smithsonian Magazine

Inevitably, some provinces were badly run and exploited by their governors. Governors were given a sum by the Senate which their province was expected to provide, any surplus was often kept by the governor. Pliny the Younger, himself a governor of Bithynia and Pontus in AD 110, wrote a series of letters to Emperor Trajan during his governorship. In these letters, Pliny tells of the poor state his province was left in by its previous governor, Julius Bassus.

Despite the burdens of subjugation, there were some systems in place to allow for local governance and influence. Panels of local nobility (consilia), which included high-ranking priests, were set up. These panels liaised between locals and the governor and also had communication directly with Rome. Many of these panel members gained Roman citizenship for their services. By the 2nd century AD, even the Roman Senate was opened up to provincial politicians.

The Roman Military

A Roman marble portrait head of Julius Caesar, late 1st century BC–early 1st century AD, via Christie’s

The stability of imperial Rome and its empire depended largely on the Roman army. However, the presence of the army within the city of Rome was political rather than military. Troops bearing arms were not allowed within the city boundaries. A Roman general was also not allowed to enter Italy at the head of his troops. This was considered an act of war against the Senate. Julius Caesar committed such an act in 49 BC when he crossed the River Rubicon, Italy’s northern border, with his legion. This led to the outbreak of the Roman Civil War.

The army was often responsible for changes in imperial power in Rome. Those who held the support of the army could gain great influence over the city. Emperor Augustus was a prime example of this. His reforms led to higher salaries and land rewards for service. In return, he gained the complete loyalty of the legions.

Partially reconstructed tomb of Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus, a Gallic nobleman who became Procurator of Britain in AD 61, 1st century AD, via The British Museum, London

As well as keeping law and order, the army in the Roman provinces played an important social role. It helped to spread Romanization (Roman culture and infrastructure) across the empire and enabled social mobility.

Most provinces had permanent garrisons rather than entire legions. But throughout the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, there were between 25 and 30 legions stationed across the empire. These were mostly found in frontier provinces where protection was necessary. The Augustan reforms allowed auxiliary regiments to recruit from the provinces and these recruits received Roman citizenship on discharge. Provincial soldiers would often take the nomenclature of the emperor who had granted them their citizenship. For example, there were many Gaius Juliuses to be found in Gaul named after Augustus. Inscriptions show that some of these men became successful in business or local politics.

The Temple of Augustus’ Sons in Nîmes, France, known today as the Maison Carrée, 1st century AD

The army was also responsible for building infrastructure in the Roman provinces, such as temples, roads, aqueducts, and bridges. Many examples can still be seen today such as the long, straight Roman roads of England and the magnificent Roman temples of France.

Retired soldiers, who originated from Italy, often developed close ties with the province in which they had been stationed. Many stayed after service, married local women, and set up home there permanently. The families of these retired soldiers also gained Roman citizenship.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a large number of writing tablets were discovered at Vindolanda, a Roman fort on Hadrian’s Wall in northern England. These tablets offer a fascinating insight into daily life in and around a provincial fort. Particularly interesting are the personal messages. Letters to and from family members have been found and there is even an invitation to a birthday party.

Trade And Commerce

Terracotta Roman storage amphora used to transport wine or oil across the empire, 1st century AD, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Imperial Rome was a cosmopolitan city full of wealth. But it was also very large and not at all self-sufficient. Many of its basic goods, such as wine, olive oil, and grain, had to be imported from elsewhere. The Roman provinces were essential in providing for the inhabitants of Rome.

To accommodate the large number of ships arriving with produce for Rome, the port of Ostia grew up 15 miles southwest of the city. Imported goods were loaded onto barges and then transported up the River Tiber towards the city. The site of Monte Testaccio in Rome is a great symbol of the city’s huge levels of consumption. This enormous pile of broken pottery consists of thousands of Spanish oil amphorae which were discarded after use over many centuries. The mound can still be seen today and is 35 meters high and almost a kilometer in circumference.

A collection of terra sigillata made in Africa and Gaul and discovered in Liguria, Italy, 1st century AD, via The British Museum, London

In comparison to Rome, some provinces were hubs of industry. The Roman provinces of Egypt and Africa Proconsularis supplied the majority of the wheat for Rome. Egypt was also a main center of papyrus production and was an important trading point with India. Excavations at Egyptian ports have unearthed everything from Chinese porcelain to Indian spice jars and textiles.

Pottery can be a useful indicator of local trade. In various provinces from Gaul to Africa a specific type of red slipware, known as terra sigillata, was produced. This pottery was exported across the empire and beyond. There were also high levels of economic activity in locations at which Roman legions and garrisons were stationed. This was due to the large quantities of goods imported to these areas and also soldiers spending their salaries locally. Whole towns often developed around Roman forts in order to provide the military with everything that they might need.

Religion In Imperial Rome And The Roman Provinces

Silver Mildenhall Great Dish depicting various Celtic and Roman deities, 4th century AD, via The British Museum, London

Religion in imperial Rome permeated nearly every aspect of daily life. The pantheon of Roman gods and goddesses, each with their own particular sphere of influence, was a focus of worship for all, from emperors to slaves. In the 2nd century AD, the Roman state religion suffered a decline in popularity. Instead, the exotic Eastern cults, such as those of Cybele, Isis and Mithras, became very popular.

These Eastern cults originated from territories that became a part of the Roman Empire. Cybele and Isis came from the Roman provinces of Asia and Egypt, respectively. In the northern part of the Empire, Celtic religion was the dominant force. Celtic culture covered a vast geographical area from Britain to the Balkans.

Gilt bronze head of the Celtic-Roman goddess Sulis Minerva, 1st century AD, via The Roman Baths at Bath

Rome, as a conquering force, was surprisingly tolerant of some religions in the empire. The Roman state religion was not vehemently imposed upon other cultures, rather it was often harmonized with them in the attempt to spread Roman culture. A prime example of this was the hybrid goddess Sulis Minerva. The Celtic goddess Sulis, a healing goddess local to modern-day Bath in England, was merged with the Roman goddess Minerva. This was a way of bringing together two different religious ideologies.

However, a desired state of harmony was, inevitably, not always possible in reality. Provinces that harbored consistent uprisings against Roman occupation would be met with the full force of the Roman military machine. A tragic example of this was the revolt of the province of Judea in AD 66.

Stone panel from the Arch of Titus depicting the Roman triumph after the sack of Judea, late 1st century AD, via University of Southampton

Religious intolerance had been rife in Judea for many years under successive Roman governors. The Jewish people finally rebelled against this in AD 66 and attempted to overthrow the local government. However, Rome soon brought reinforcements. The ensuing battles resulted in the deaths of over 10,000 Jewish people and the destruction of the Jewish Temple. Tensions between the Romans and the Jews continued on and off well into the 2nd century.

Roman Provinces And The Fall Of Imperial Rome

The differences between imperial Rome and its provinces ran deep. Variations existed in many essential aspects, from the way they were governed to their economies and interaction with the military. However, ultimately, imperial Rome and the Roman provinces were largely dependent on one another. It is important to note that the collapse of infrastructure in the provinces in the 5th century AD was one of the main contributors to the fall of the Roman Empire.