What Did Julius Caesar Accomplish Most Well?

Julius Caesar is history’s most famous Roman. But what were Julius Caesar’s achievements?

Gaius Julius Caesar was born on July 12th 100 BCE (though some cite 102 as his birth year). He was the son of Gaius Julius Caesar, a Praetor in the province of Asia, and his mother, Aurelia Cotta, who was of noble birth. After his rise to power, Caesar became a member of the First Triumvirate, conquered Gaul, and defeated his political rival Pompey in a civil war. Then, he became a dictator from 49 BCE until his assassination in 44 BCE. Looking at Julius Caesar’s achievements, we can see there was not a moment in his life where he did not achieve, conquer or win something.

Julius Caesar’s Ascension to Power Was an Achievement

Gaius Julius Cäsar, by Peter Paul Rubens, 1619, via the Brandenburg Museum

Julius Caesar’s ascension to power did not happen overnight and happened in spite of many obstacles. His ascension to power, therefore, deserves to be considered an achievement. It all started when Julius was sixteen, and his father died, leaving him as the head of the family responsible for caring for it.

Young Julius managed to nominate himself as the new High Priest of Jupiter, however, his troubles were far from over. As a priest, he had to be a patrician but also had to be married to one. This meant divorcing Cossutia, his first wife of plebeian stock, and marrying Cornelia, the daughter of the influential member of the Populares, Lucius Cinna.

Furthermore, when the Roman Ruler, Sulla, declared himself dictator, he initiated a systematic purge of his political enemies, focusing on those who held the Populares ideology. Threatened by the sudden turn of events, Caesar fled Rome. Fortunately, his sentence was lifted through the intervention of his mother’s family, but he was stripped of his priesthood and his wife’s dowry. With no other options left, Caesar joined the Roman army.

In Asia, Caesar was under the authority of Marcus Micinius Thermus, the provincial governor. During the siege of Mitilene, on the island of Lesbos, Caesar fought with such courage that he was awarded the Civic Crown for saving a life in battle and was promoted to become military legate to Bithynia. After Sulla died in 78 BCE, Caesar returned to Rome and became a successful orator.

The First Triumvirate

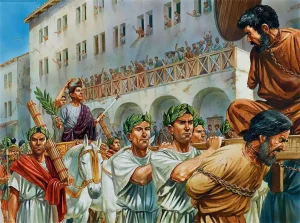

Pompey’s Triumph, by Peter Dennis, via imperiumromanum.pl

His next achievement set the stage for his road towards the dictatorship. Caesar’s initiation of the First Triumvirate began with his election as a military tribune and, after the death of his wife, with his marriage to Pompeia, the granddaughter of Sulla. With his newly obtained prestige and influence, Caesar assisted Gnaeus Pompeius in obtaining his generalship and befriended the wealthiest man in Rome, Marcus Licinius Crassus. With the latter’s wealth, Caesar rose to the position of Pontifex Maximus in 63 BCE. In the following year, he was elected as Praetor, and in 61 BCE he sailed to Hispania (Spain) as Propraetor.

His tenure as Propraetor was very successful. Particularly, through his skill and leadership, he defeated the local warring rival tribes, brought stability to the region, and won the personal allegiance of his troops. As a result, after his return to Rome with high honors, he was awarded consulship by the Senate. Furthermore, he strengthened his alliance with Pompey and Crassus by marrying Calpurnia, the daughter of a wealthy and powerful Populares senator, and he married his daughter Julia to Pompey. Thus, the First Triumvirate started turning its gears, effectively ruling Rome for some time.

The mechanism was simple. Caesar, as consul, proposed and pushed measures favored by his two political companions. He initiated several reforms in the spirit of the Populares ideology, such as a redistribution of land to the poor. In these, Crassus supported Caesar financially and Pompey militarily. While his consulship lasted, Caesar was safe from prosecution by his opposition, the Optimates. Toward the end of his consulship, he realized he was deeply in debt to Crassus, financially and politically, and needed to raise money and gain prestige to survive.

The Gallic Wars

Vercingetorix throws down his arms at the feet of Julius Caesar, by Lionel Royer, 1899, via Wikimedia Commons

One of Caesar’s most significant military achievements, the Gallic Wars, began with a cry for help sent by the Haedui tribe. After occupying the northern part of the city of Lugudunum (in Lyon, France), they needed protection against the rival tribe of the Helvetii. In desperate need of funds and prestige, Caesar saw the opportunity of the gallic request. As such, in 58 BCE, he and his army marched north, where he won his first major victory at the Battle of Bibracte, defeating the Helveti and forcing them and their allies to retreat. Caesar recorded this and the following battles in his De Bello Gallico, his written account of the Gallic Wars.

Following the defeat of the Helvetii, the Haedui allied themselves with other tribes, the Secvanii and the Suebii. The latter, led by Ariovist, slowly approached Gaul, threatening Caesar’s interests. In Alsace, the two leaders met, but the Ariovist refused Caesar’s request to retreat. As a result, after ten days, their armies clashed at Mullhousen, and Caesar won again. Defeated, Ariovist retreated beyond the Rhine, and for two centuries, the middle of Gaul remained under Roman control.

However, for Caesar, this was just the first step in his plans for Gaul. Further, he profited from the constant quarrels between tribes, involving himself in internal conflicts to either earn their trust or weaken them. Additionally, he defeated the Belgae in 57 BCE and the Aquitani in 56 BCE.

The end of his campaign in Gaul began in 55 BCE when, after defeating the Usipetri, Sugambri, and Tencteri, Caesar reached the lower Rhine. Here, in 52 BCE, at the Battle of Alesia, he defeated Vercingetorix, ending the Gallic Wars and completely conquering Gaul.

Crossing the Rubicon

![]()

Julius Caesar Crossing the Rubicon, by Philip de László, 1891, via de Laszlo Archive Trust

His next military achievement was instrumental to his plans. Following his victory in Gaul, Caesar returned to Rome and received an honorary welcome celebration. Fearing his status, Caesar renewed his political alliance with Pompey and Crassus, each promising the other to act only for their common interests. Further, Crassus and Pompey became consuls, and all three shared territories between themselves. Caesar kept Gaul for another five years, while Pompey received Hispania and Crassus, Syria.

Unfortunately, it was not to last. The First Triumvirate started crumbling with the death of Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae and with the death of Julia in childbirth. For Pompey, this meant losing his ties to Caesar and his financial and political backer. Therefore, he aligned himself with the Optimate faction in Rome, which he had long favored, and became the sole military and political power.

In his new position, Pompey convinced the senate to declare Caesar’s governorship of Gaul terminated and ordered him to return to Rome as a private citizen. This meant Caesar could be prosecuted for his actions when he was consul.

Bust of Julius Caesar, by Andrea di Pietro di Marco Ferrucci, 1512-4, via the MET Museum

On the 11th of January, 49 BCE, Caesar crossed the Rubicon river, initiating a five-year-long civil war. In only two months, he conquered the whole of Italy and then Pompey’s Spanish provinces after the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE. Pompey escaped to Egypt to find allies from his previous visits. Unbeknown to him, Ptolemy XIII, the Egyptian ruler, heard the news of Caesar’s victory and, believing that the gods favored Caesar over Pompey, had Pompey murdered. Caesar, outraged over Pompey’s death, allied himself with Cleopatra VII, and together they deposed Ptolemy.

After securing his alliance with Egypt, Caesar obtained three more significant victories. He defeats Pharnakes, the king of Bosporus and an ally of Pompey, at the Battle of Zela in 47 BCE. The following year, he defeats Cato and Sextus Pompeius at the Battle of Thapsus in Africa. His final victory was against Pompey’s children at the Battle of Munda in 45 BCE.

Dictatorship: The Last of Julius Caesar’s Achievements

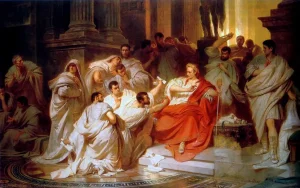

The Murder of Caesar, by Karl von Piloty, 1865, via Landesmuseum Hannover, via Wikimedia Commons

Caesar’s rise to dictatorship took place during the civil war against Pompey. He first received the title in 49 BCE and held it for eleven days. Next, following his victory against Pompey’s forces in 48 BCE, his title was renewed for a year. He received another ten-year extension after his victory at Thapsus in 46 BCE. Finally, after winning the civil war, he received, in 45 BCE, the title of Dictator Perpetuus (dictator for life).

After this point, Caesar focused on reforms to stabilize Rome and he introduced the Julian Calendar (365 days, with one leap year after 4 years). While he kept all Roman institutions, the political power resided only with him, leading to animosity among his adversaries. Besides the title of dictator, Caesar held the title of consul and high priest. The final straw that led to his eventual assassination was his choice of garments during the festival of Lupercalia. On the 15th of February 44 BCE, Caesar appeared wearing symbols of the old Roman kingship. Specifically, a purple-colored cloak and a gold crown. Following this display, on the 15th of March, a group of conspirators, led by Marcus Iunius Brutus, Caius Cassius, and Servilus Casca murdered Caesar on the floors of the Theatre of Pompey.