The School of Athens vs. Dante’s Inferno: Intellectuals in Limbo

Dante’s Inferno and Raphael’s The School of Athens provide two different perspectives on Antiquity’s thinkers. Raphael bathes them in sunlight, while Dante condemns them to the limbo-level of hell.

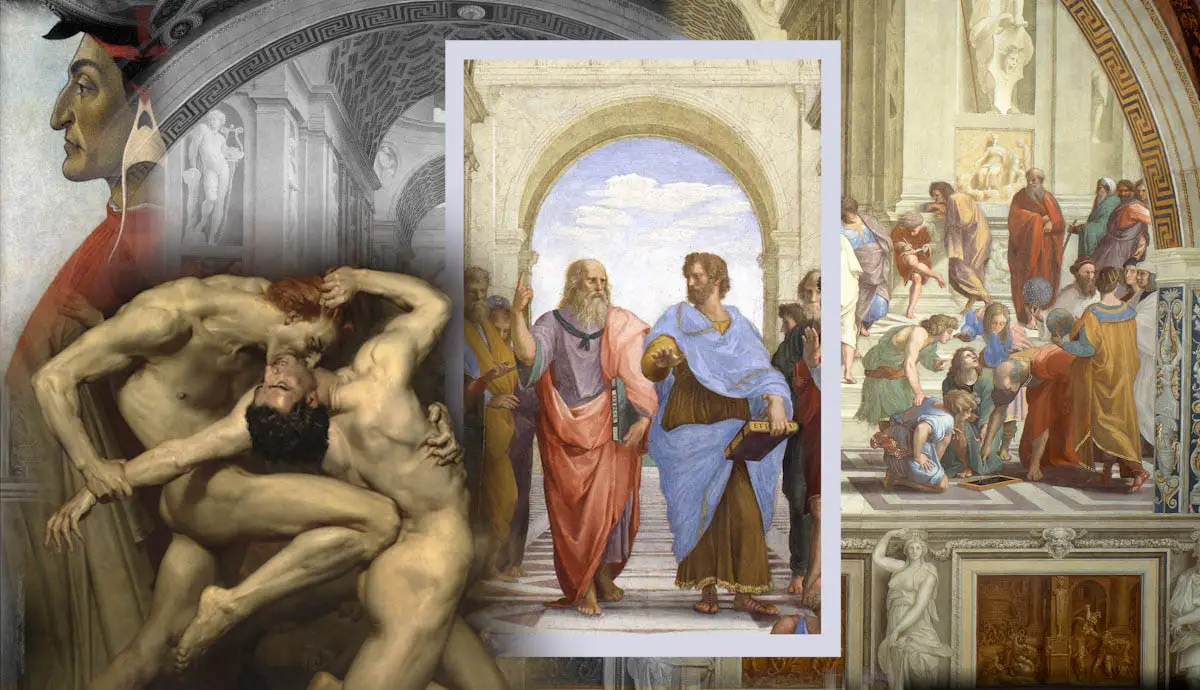

The School of Athens by Raphael, 1511, Vatican Museums; with Dante and Virgil by Bouguereau, 1850, via Musée d’Orsay; and Dante Alighieri, by Sandro Botticelli, 1495, via National Endowment for the Humanities

When a great thinker has an idea, it lives on even after his death. Even today, the ideas of Plato, Socrates, and Pythagoras (to name a few of Antiquity’s A-listers) remain potent. The tenacity of these ideas makes them open for any and all debate. With each new historical context, new artists provide new perspectives on Antiquity.

During the medieval period, Classical contributions were viewed as the mere musings of unbaptized heretics, so-called “Pagan souls.” During the Renaissance, Classical thinkers were revered and imitated. These two starkly different perspectives manifest in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno and Raphael’s The School of Athens. What do these two men, and their respective societies, have to say about the great thinkers of Antiquity?

The School Of Athens By Raphael In Comparison To Dante’s Inferno

The School of Athens, Raphael, 1511, Vatican Museums

Before our deep dive into hell, let’s examine The School of Athens. The School of Athens is an early Renaissance painting by The Prince of Painters, Raphael. It portrays many of the big names in Classical thought standing in an arcaded room, bathed in sunlight. Remember that Raphael is a Renaissance painter, working about 200 years after Dante’s Inferno.

Raphael celebrates Antiquity with this painting. By Renaissance standards, the mark of true intellect and skill was the ability to imitate and improve upon Greek and Roman ideas. This practice of reinventing Classical ideas is known as Classicism, which was a driving force of the Renaissance. Greek and Roman works were the ultimate source material. Through his depiction, Raphael attempts to draw comparisons between the Renaissance movement’s artists and Antiquity’s thinkers.

Raphael does not concern himself with historical accuracy; many figures are painted to resemble his Renaissance contemporaries. For instance, notice Plato, wearing the purple and red robe, who attracts our eye at the center of the painting. Plato’s likeness actually shows a strong semblance to Leonardo da Vinci, based on his self-portrait.

Raphael’s decision to depict Plato as da Vinci is very intentional. Da Vinci was about 30 years older than Raphael, and he had already made significant contributions to the Renaissance. Da Vinci himself was the inspiration for the term “renaissance man.”

Blurring the line between his own contemporaries and their Classical antecedents, Raphael makes a bold statement. He is claiming that Renaissance thinkers draw on the deep wealth of Classical thought and he seeks to be counted as their equal. Keeping Raphael’s perspective in mind as someone who hopes to garner glory via imitation, let’s move to Dante’s Inferno’s complex case.

The Context Of Dante’s Inferno

La Divina Commedia di Dante, Domenico di Michelino, 1465, Columbia College

Dante Alighieri, the author of the three-part epic poem, The Divine Comedy, presents us with an incredibly conflicted perspective on Antiquity. His views echo the larger perspective shared by his medieval contemporaries.

Dante himself was a prominent man in Florentine politics. Born in Florence, Italy, in 1265 Dante was a prominent, yet complicated political and cultural figure. He was exiled from his hometown of Florence, during which time he began writing the Divine Comedy.

The draw to read and understand Dante continues to captivate readers to this day. While the text is nearly 700 years old, it remains engaging for us to imagine life after death. Dante’s Inferno brings us down through the winding trenches of hell for a meet-and-greet with history’s most irredeemable.

The narrative Dante weaves is incredibly complex, to the point that even today readers can get tangled up in the densely woven web of the underworld. One cause for confusion is the fact that Dante functions as both the writer, as well as the main character. Dante the writer and Dante the character can also appear at odds, at times.

Dante’s punishments, sentenced for eternity, are designed to fit the crime: the lustful unable to make contact with one another due to gusting winds, the violent swim in a boiling pool of blood they spilled, and the treacherous are chewed on by Lucifer himself.

While Dante envisions deeply disturbing scenes, his Inferno is far from a medieval burn book. Inferno also wonders aloud about merit and punishment. In his consideration of Classical figures, we see how Dante’s jury is still out on several of Antiquity’s key thinkers.

Dante’s Journey Into Hell

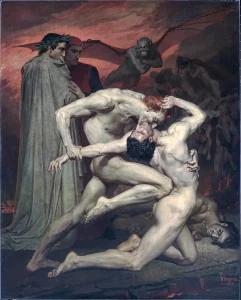

Dante and Virgil, William Bouguereau, 1850, Musée d’Orsay

When Dante imagines the afterlife, he picks Virgil to guide him through hell. Virgil is wise enough to guide Dante, while Dante simultaneously condemns him to hell. A contemporary reader may feel compelled to call this a “backhanded compliment.”

Why does Dante admire Virgil? Virgil is the author of the epic poem the Aeneid. The Aeneid recounts the journey of Aeneas, a scrappy Trojan soldier who would go on to found Rome. Aeneas’ journey, half truth and half legend, had adventures all over the world. Painters across time periods would depict this poems’ most compelling scenes. In penning this poem, Virgil himself also became something of a legend. To Dante, Virgil is “the Poet,” functioning as both a literary role model and mentor on his journey in understanding the afterlife.

Dante, poised as the naïve visitor in hell, relies on Virgil to explain what he does not understand. However, Virgil is a Pagan soul. He existed before he could know Christianity. Despite the wisdom and mentorship Virgil offered, in Dante’s perspective, he is still an unreformed soul.

First Stop: Limbo

Dante and Virgile, also called La barque de Dante (The Barque of Dante), Eugene Delacroix, 1822, Louvre

In the map of Hell, Limbo is like the pre-layer. The souls here are not punished per se, but they are not afforded the same luxuries of those in heaven. Unlike other souls in Purgatory, they are not offered the opportunity to redeem themselves.

Virgil explains the precise reason why souls end up in Limbo:

“they did not sin; and yet, though they have merits,

that’s not enough, because they lacked baptism,

the portal of the faith that you embrace.” (Inf. 4.34-6)

While Dante the writer agrees that Classical figures have contributed a great deal to our cultural canon, their contributions are not enough to exempt them from having undergone proper Christian rites. However, Dante the character feels “great sorrow” upon hearing this information (Inf. 4.43-5). Despite Dante the character pitying the souls, Dante the writer has left these “…souls suspended in that limbo.” (Inf. 4.45). Once again, Dante exhibits restraint in celebrating these thinkers, while also admiring them deeply.

The geography of Limbo contrasts with later circles; the atmosphere deeper in hell is so blood-stained and bone chilling that Dante is prone to fainting (as seen in the above renditions). The geography of Limbo is more welcoming. There is a castle surrounded by a steam and “a meadow of green flowering plants” (Inf. 4.106-8; Inf. 4.110-1). This imagery parallels Raphael’s School of Athens, as these Pagan souls are depicted in a wide-open space within a larger stone structure.

Who do Dante and Virgil meet in Limbo?

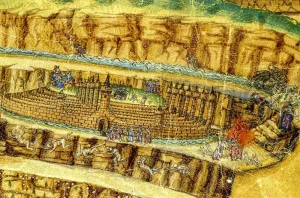

Detail of the Noble Castle of Limbo, from A Map of Dante’s Hell, Botticelli, 1485, via Columbia University

Like Raphael, Dante also name-drops several significant Classical figures.

To name a few of the figures Dante sees in Limbo, we realize how well-read Dante must have been. In Limbo, he points out Electra, Hector, Aeneas, Caesar, King Latinus, and even Saladin, Sultan of Egypt in the twelfth century (Inf. 4.121-9). Other notable Classical thinkers found in Limbo are Democritus, Diogenes, Heraclitus, Seneca, Euclid, Ptolemy, Hippocrates, (Inf. 4.136-144). From this (only partially relayed) list of figures in Limbo, scholars begin to wonder what Dante’s library looked like.

Of more significance, Dante also notices Standing nearby Aristotle are also Socrates and Plato, who are standing nearby “the Poet,” Aristotle (Inf. 4.133-4). When referring to Aristotle, Dante uses the epithet: “the master of the men who know” (Inf. 4.131). Similar to how Virgil is “the Poet,” Aristotle is “the master.” To Dante, Aristotle’s breakthroughs are the apex.

But above all, Dante is most honored by meeting several other Classical poets. The four big names in classical poetry: Homer, Ovid, Lucan, and Horace are also in Limbo (Inf., 4.88-93). These poets greet Virgil happily, and the five writers enjoy a brief reunion.

And then, something marvelous happens to Dante the character:

“and even greater honor then was mine,

for they invited me to join their ranks—

I was the sixth among such intellects.” (Inf. 4.100 – 2)

Dante the character is honored to be counted among the other great writers of classical works. While he has varying degrees of familiarity with each work (such as being unable to read Greek), this gives us a window into the cultural canon Dante consumed. In fact, Dante’s Inferno is laden with references, allusions, and parallels. While Dante punishes the Pagan souls, he also clearly had avidly studied their works. In this way, Dante is also imitating his predecessors. From this line, we see that the aspirations of Dante’s Inferno and Raphael’s School of Athens are aligned. Both want to emulate aspects of Antiquity in order to achieve greatness.

The Gates of Hell, Auguste Rodin, via Columbia College

Since Dante’s Inferno is a literary work, we rely a tremendous amount on description to paint the picture. One way Dante’s consideration of these figures differs from Raphael is how they treat the figure’s faces. Dante remarks:

“The people here had eyes both grave and slow;

their features carried great authority;

they spoke infrequently, with gentle voices.” (Inf. 4.112-4)

Contrast these “gentle voices” with Raphael’s depiction. In The School of Athens, we can almost hear the great, booming orations of the intellectuals. Raphael communicates respect and reverence through body language and posture in his painting.

Dante’s Inferno, however, emphasizes the silence, exasperation, of the Pagan souls. They are wise, but they are to be forever tormented by an eternity without hope of salvation. Their contributions, unable to outweigh their lack of faith, cannot redeem them. And yet, Dante the character felt tremendous honor to have witnessed them (Inf. 4.120) Despite their Limbo status, Dante the character is humbled to have been in their presence.

Dante’s Inferno Remains Potent

Dante Alighieri, Sandro Botticelli, 1495, via National Endowment for the Humanities

Above all, studying these two time periods illustrates that ideas are always under scrutiny. While one generation may have mixed feelings about certain perspectives, the next generation may embrace them to their fullest extent. From these two works, we see similarities of perspective on Antiquity. The School of Athens seeks to shout their praises from the rooftops. While Dante is more reserved and conflicted about admiring unbaptised souls, he also seeks to emulate them, like Raphael.

In many ways, Dante gets his wish. We are still debating the questions eternal raised in his work: What awaits us after death? What warrants salvation and punishment? How will I be remembered? It is due to Inferno’s evocative engagement with these questions that we continue to be mesmerized by Dante. From the way artists have rendered his poetry into paintings, to the Disney film Coco incorporating a Xolo dog named Dante as a spirit guide, Dante’s Inferno continues to intrigue us.