The History, Use, and Future Goals of the Torah

The name of the Torah has a complicated history. It has been thought to mean a multitude of things including “instruction”, “law”, and “teaching”. The Torah is often misunderstood to represent the Hebrew Bible, but in fact only actually covers the first five books, known as the Pentateuch, out of the total twenty-four. While some consider the Torah to represent the entire narrative of the Hebrew Bible, others associate the title with the entire range of Jewish literature, practice, and religious teachings.

Those who consider the Torah to be the entirety of Jewish practices the Torah specifically denote the book as the “Oral Torah”, as the items confined within it are those which were not described in the first five books of the Hebrew Bible but rather the items that became practices through laws or interpretations. While the exact nature of the Torah can be debated among practitioners of the Jewish faith, all agree that the primary purpose of the Torah is to divulge the heritage of the Jewish people and the ways of life ascribed to them by God.

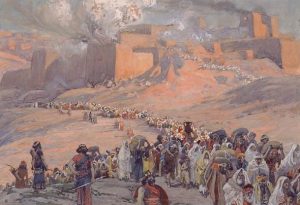

The Flight of the Prisoners, by James Tissot, depicts the destruction of Jerusalem at the hands of the Babylonians. (Public domain).

Origin of the Torah: Replacing the Temple During the Babylonian Captivity

Scholars continue to debate when the Torah was written, but it is most often believed to have been recorded during the Babylonian captivity which occurred between the 6 th and 7 th centuries BC. The Babylonian captivity was a time in Jewish history when the people of Judah were taken by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and held captive in Babylon. The infamous King Nebuchadnezzar had forced Jerusalem into a subordinate position, requiring a tribute from them each year. At the same time, some noble youths were taken as captives to Babylon.

Years later during a second siege, circa 597 BC, the Temple of Jerusalem was pillaged and more members of the nobility were captured. The temple was pillaged once again in 587 BC by Nebuchadnezzar, and subsequently destroyed. The Torah was supposedly recorded during this time to serve as an authoritative text while the people of Judah were held in Babylon. It is thought that the Torah replaced the temple as the center of religious worship, since the Jews themselves were forcibly distanced from their previous religious gathering centers.

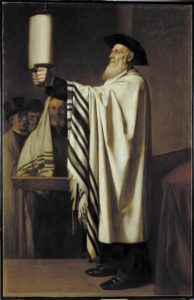

This 1860 painting by Édouard Moyse, entitled Presentation of the Torah, shows the ritual use of the Torah in readings, known as parashah. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Torah as Central to Jewish Religious Worship

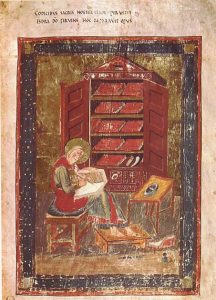

The Torah plays a powerful role in Jewish tradition. It is at the center of all religious worship, which requires the reading of sections of the Torah in a public setting, most frequently in a synagogue. According to legend, the reading of the Torah publically was first begun by Ezra the Scribe in the 6 th century BC, following the Babylonian captivity. Ezra himself, believed to be a descendent of the last High Priest of the First Temple of Jerusalem, therefore transformed the practice into ritual. Ezra himself also supposedly enforced the idea of utilizing the Torah as the central focus of religious worship following the Jewish captivity.

Readings of the Torah are referred to as parashah, or the weekly Torah portion, and are expressed in weekly sessions of worship, usually on Saturdays, the Sabbath. The parashah are comprised of the five books of the Torah, each broken into seven sections. Each is titled with the first words of the Hebrew Bible written on the first page.

Ezra the Scribe, from the Codex Amiatinus, credited as being the first person to read the Torah publically in the 6 th century BC, following the Babylonian captivity. (Public domain)

Bereshit: The Book of Genesis

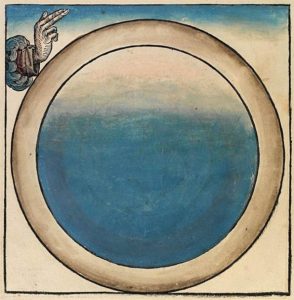

Bereshit means “in a beginning”, and is the first Torah portion read during the annual prayer services. It discusses Genesis and the creation of the world until the coming of Moses. It is likely entitled Bereshit due God’s creation of everything from the beginning onward. The story of the beginning according to the Torah is as follows: The earth is created from the darkness and the void in seven days. God speaks into existence first light, then a firmament which divided waters to create land. Next, God created vegetation, the days and years along with the celestial bodies, and finally living creatures. On the sixth day, God created humans and gave humanity power over animals. On the seventh day, God rested. Bereshit continues to describe God’s creation of Eden and the tree of knowledge, and Adam and Eve’s role in the Garden of Eden as well as the Fall.

Bereshit further describes the aftermath of the fall of Eden and the after effects of sin in the world by describing various biblical narratives. The story of Cain and Abel, the children of Eve and Adam, is described, wherein Cain kills Abel and is damned by God to wander forever for his crimes. Cain’s descendent Lamech comes next in the narrative, followed by the continued birth of children by Adam and Eve, with the final tale in the narrative being the Great Flood and Noah’s Ark. Noah, in the Hebrew telling of the story, is the son of another Lamech, and he is granted God’s favor despite the extensive wickedness of man and God’s determination to destroy His Creations. In total, there are seven readings in the parashah Bereshit.

Depiction of the First Day of Creation, one of the stories within the Book of Genesis, as illustrated within the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle. (Public domain)

Shemot: The Book of Exodus

The next significant annual Torah reading is the parashah called Shemot, number thirteen on the reading list. Just as Bereshit described the events of the Book of Genesis, Shemot deals explicitly with the Book of Exodus, wherein the Israelites suffered in Egypt. Shemot is also broken into seven sections. It opens with the coming of the descendants of Jacob, the son of Isaac and Rebekah and considered the father of the Israelites, to Egypt. The rise of a new Pharaoh during their time in Egypt led to the Egyptians forcing the Israelites into slavery. Meanwhile the new Pharaoh also demanded the death of all male children by Hebrew women, in an attempt to control the population of the Israelites. It is believed that the children were not killed out of a fear of God and compassion.

Into this tumultuous scene Moses is born, discovered on the banks of the Nile and later adopted by the Pharaoh’s daughter. The remainder of Shemot goes on to dictate the story of Moses: his killing of an Egyptian in vengeance for the beating of another Hebrew, the bounty placed on his head by the Pharaoh, and his escape to the life of a shepherd. It was during his time living as a shepherd, married to a woman named Zipporah, that God spoke to Moses from the Burning Bush and instructed him to rescue the Israelites in Egypt. With the rod of God, Moses goes to the Pharaoh and attempts to have his people freed, but is sorely rejected by the Pharaoh who does not believe in the power of God.

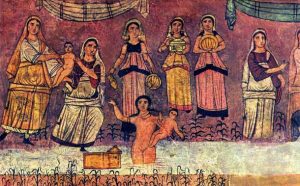

Depiction of Moses being found by the river, from a fresco at the Dura Europos synagogue. The story is part of the Shemot, or the Book of Exodus. (Public domain)

Vayikra: The Book of Leviticus

Following Shemot, which ends prior to Moses’ actual freeing of the Israelites through the Red Sea, the Torah reading of Vayikra is the third significant parashah. Vayikra is the twenty-fourth portion of the Torah reading cycle, and dictates the Book of Leviticus, the third book of the Old Testament and of the Torah. Here, Moses’ story is continued through God’s detailing of the rules of sacrifice and feasting to Moses. God describes the appropriate animals to be burnt as being bulls, rams, goats, turtle doves, and pigeons, whereas offerings of “well-being” could be cattle, sheep, or goats, all of which were to be burnt on a wood altar. Also described are sin offerings and guilt offerings: the former in cases where sinner did something unclean or untrustworthy, while the latter were reserved for those who forgot to engage in something sacred. Essentially, the parashah Vayikra clarifies the purposes of sacrifice and the types of sacrifice allowed in the Jewish tradition.

Bemidbar: The Book of Numbers

The next parashah which should be highlighted when discussing the Torah is Bemidbar, which stems from the Book of Numbers in the Hebrew Bible. It is the thirty-fourth in the annual Torah reading cycle, and specifically discusses the duties of priests, as well as continuing the story of Moses. Just as Vayikra dictated the use of sacrifice through the role of Moses in the Bible, so does Bemidbar dictate the role of priests and the census through Moses’ life.

First, Bemidbar describes Moses’ taking of the first census of the Israelite men, distinctively noting the men who were eligible to fight in an army; that list is then divided to show the number of men in each of twelve tribes. The Levites, in particular, were not included in the census upon God’s instructions, as they were instead given responsibility of the Tabernacle, or the Tent of Meeting. Because of their educational and political duties to the Israelites, they were exempted from the census. A further subgroup of the Levites, called the Kohanim, were the priests of the tradition, performing the religious duties necessary to appease God. God also instructed Moses to take a count of all the firstborn sons of the Israelites.

As described in the Book of Deuteronomy, this tapestry from the 1550s by Jan de Kempeneer depicts Moses receiving the tablets. (Public domain)

Devarim: The Book of Deuteronomy

The final parashah in need of description is Devarim, the forty-fourth of the annual Torah readings, and dictating the Book of Deuteronomy. This section of the Torah readings recounts the movement of Moses and the Israelites from Egypt and their subsequent actions during this time. During their transition from Mount Sinai to Canaan, for example, Moses orders leaders to be chosen from among the tribes to contend with any issues or inner squabbles that might arise, so that Moses himself could continue to focus on more important concerns.

This selection of the first chiefs of the tribes is therefore attributed as one of Moses’ many achievements. The Israelites move into the land of Kadesh (sometimes written as Qadesh) on God’s orders, eventually continuing on to Jordan, where Moses designated the borders of the land for settlement. Throughout their travels, lasting decades, the Israelites found conflict with the Amorites and the people of Bashan. At the conclusion of their journey, three of the tribes found land to settle on the eastern side of the Jordan River.

The Torah in Judaism, Christianity and Islam

While the Torah can be read throughout the year, the annual reading of the Torah in its particular order is important within the Jewish community. The completion of these five readings is significant in religious expression, and is celebrated each year during the Jewish holiday Simchat Torah, meaning the “Rejoicing of the Law”. The title describes the celebration of finishing the code of Judaism in 54 (sometimes 55 or even 53) weeks.

The Qur’an and Torah on the True Meaning of the Tower of Babel and Multiple Languages

Can Jewish People be a Nation, and a Religion, and a Race?

The Dramatic Reign of Nebuchadnezzar II

While the Torah is most important for the followers of Judaism, it does also play a role in other religions. Christianity takes its Old Testament from the Torah, though the version recorded in the Christian faith is not exactly the same as that which is written in Hebrew. In Islam, the Torah is referred to as the Tawrat, and is believed to have been sent by God (Allah) to Moses (Musa) and thus, to the people of the world. Interestingly, in Islam, the Torah is mentioned, a significant number of times, as a body with which they governed the people in legal matters as well as in religious matters. It is believed that the Quran replaced the Torah as the primary book of Islam long ago, but the presence of the Torah in Quran teachings evidently survives via its numerous references.

The Torah is best known for its role in Jewish culture, and is often mistakenly considered to be merely the first five books of the Christian Bible. In fact, the text is far richer than that, and should be suitably valued for its religiosity. A reading of the Old Testament does not equate to a reading of the Torah, and the extensiveness of the trials and tribulations of the Israelites contained within the books of the Torah is profound.

Any linguist scholar can advocate how much is lost in the translation of one text into another language, and the same can undoubtedly be said for the translation of the Hebrew text into Latin, Ancient Greek, or any other language. For a more thorough understanding of the sheer monumentality of the Torah, it is highly encouraged one attempt to read it personally. Though this article attempts to cover the extent of the Torah, it does not by any means replace the detail contained within this sacred and ancient biblical literature.