The Gallic Wars and Julius Caesar’s Conquest of Gaul (Modern France)

The Gallic tribes had large cities, complex political structures, great wealth, and military power. However, Caesar’s Gallic Wars brought Gaul under Roman control.

Jan 16, 2021 • By Robert C. L. Holmes, MA Ancient & Medieval History, BA Archaeology

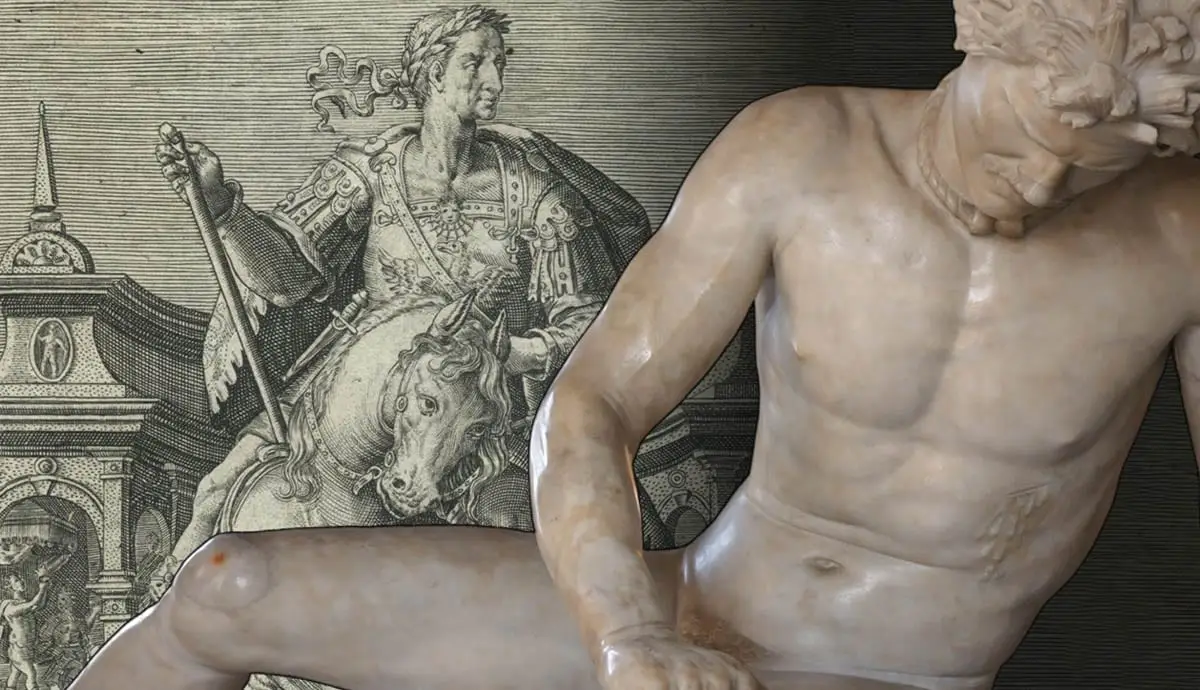

C. Ivlivs Caesar by Crispijn de Passe the Younger after Jan van der Straet, 1620-70, via the British Museum, London; with Statue of the Capitoline Galata, 1st or 2nd century AD, in The Capitoline Museums, Rome

Caesar’s Gallic Wars were one of the most important conflicts of the ancient world. It brought a vast, wealthy region under Roman control and helped elevate the political and military power of Julius Caesar. Caesar’s Gallic Wars were well documented in antiquity. The most important record was written by Julius Caesar himself, for political and propaganda purposes. As such, his account needs to be approached with some skepticism. Caesar’s Gallic Wars are presented in his account as preemptive or defensive actions in which the Gauls suffered enormous casualties with minimal Roman losses. This is unlikely, as Caesar used the conflict to boost his political career, and the Gauls had a military equal in power to that of Rome.

Julius Caesar Plots A War

Vignette with profiles of the three Triumvirs by Raphael Morghen after Giovanni Battista Mengardi, 1791-94, via the British Museum, London

The end of his term as Consul in 59 BC saw Caesar in deep financial debt. Hoping to recoup his losses, Caesar used his position in the First Triumvirate to secure himself the governorship of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum for a five-year term. His plan appears to have been a war of conquest in the Balkans, possibly directed at the kingdom of Dacia. To this end, he had four veteran legions under his command: Legio VII, Legio VIII, Legio IX, and Legio X. However, when the governor of Transalpine Gaul died suddenly, Caesar was awarded the governorship of this province as well.

As governor of Transalpine Gaul, Caesar soon found himself approached by envoys from the Helvetian tribe, which disrupted his plans. The Helvetians were a Gallic tribal confederation on the Swiss plateau. Under increasing pressure from the Germanic tribes to their North and East, the Helvetians planned a mass migration that would take them through Transalpine Gaul and the territory of the Aedui, a tribe allied to Rome. It was feared that the Helvetian migration would plunge Gaul into chaos and that the warlike Germanic tribes would move into the vacant Helvetian lands. As such, Caesar denied the Helvetian’s request to pass through Transalpine Gaul. The Helvetians, therefore, turned to the north, avoiding Roman territory entirely; seemingly resolving the crisis.

58 BC: Caesar’s Gallic Wars Begin

Gold Aureus of Julius Caesar with a woman and Gallic Trophies, 48-47 BC, via the British Museum, London

Julius Caesar saw in the migration of the Helvetians an opportunity that was too good to ignore. By defeating the Helvetians, Caesar believed that he could both enhance his political career and pay off his debts with the spoils he collected. With this in mind, even as Caesar negotiated with the Helvetians over passage through Roman lands, he was also gathering additional soldiers. Now, with 24,000 to 30,000 troops under his command, Caesar set off in pursuit of the Helvetians, who were now marching away from Roman territory. Caesar caught up with the Helvetians as they were in the process of crossing the Saone river; by this time, almost three-quarters of the Helvetians had crossed to the other side. The Romans slaughtered the Helvetians who had not crossed the river, then built a pontoon bridge to facilitate their own crossing.

As the Romans continued to shadow the remaining Helvetians, negotiations were again attempted. Caesar’s harsh terms were rejected, and when his supplies began to run out, forcing him to alter the route of his march, the Helvetians attacked. The final battle between the Romans and Helvetians was hard-fought; at one point, the Roman army was surrounded. Eventually, the Romans emerged victoriously, and the Helvetians were ordered back to their lands. There the Helvetians would form a buffer between Rome and the fearsome Germanic tribes.

Gauls, Germans, And Politics

Gallic Silver Coin, 1st century BC; with Gallic Copper Alloy Coin, 1st century BC, via the British Museum, London

Caesar received congratulations from many of the Gallic tribes including the Aedui, longstanding allies of Rome, who now requested he attack the Germanic Suebi. Several years earlier the Suebi had migrated into the territory of the Gallic Sequani, where they were offered land in exchange for military assistance against the Aedui. It was feared that as more and more Germans arrived, they would eventually take over all the Sequani territory and then threaten all of Gaul. However, the Suebian king Ariovistus had also been declared a “king and Friend of the Roman people,” so Caesar could not just attack.

Sensing an opportunity to continue his conquests, Caesar presented Ariovistus with a list of harsh demands. These demands required that the Suebi were to return all hostages they had taken, protect all other friends of Rome, including the Aedui, and all Germans were to return to the eastern bank of the Rhine and never again cross into Gaul. Ariovistus ignored the demands, which he claimed Caesar had no authority to make. Suebian attacks on the Adeui continued, more Germans crossed the Rhine, and Caesar had another war on his hands.

Subduing The Suebians

Ariovistus’ Meeting with Caesar by Johann Michael Mettenleiter, 1808, via the British Museum, London

The Romans soon learned that Ariovistus was planning to capture Vesontio, the largest city in the Sequani territory. Through a series of rapid marches, the Romans managed to arrive first. Caesar and Ariovistus made a show of attempting to negotiate a settlement over the course of the next few days, but both repeatedly violated the terms of the meetings and deliberately incited each other to war. Ariovistus marched behind Caesar’s camp and cut his supply lines. In response, Caesar built a new camp closer to Ariovistus’ army in order to entice the Suebians into giving battle.

Ariovistus launched an attack on Caesar’s camp but was repulsed. The next morning both armies assembled once again to give battle. Once again, it was the Romans who emerged victorious from the ensuing battle, largely thanks to a timely cavalry charge. The Suebians suffered heavy casualties and fled back across the Rhine. This victory brought the campaigning season of 58 BC to an end. Caesar returned to Cisalpine Gaul to oversee the non-military aspects of his governorship. It’s possible that at this point, Caesar had already decided to conquer all of Gaul.

57 BC: Battling The Belgae

Gallic Coin of the Suessiones, 1st century BC; with Gallic Copper Alloy Bracelet, 1st century BC, via The Met Museum, New York

Early in 57 BC, Caesar was once again called on to intervene in another intra-Gallic conflict, thus continuing Caesar’s Gallic Wars. The Remi, a tribe allied with Rome, were attacked by the neighboring Belgae confederation. After failing to take the largest city of the Remi, the Belgae encamped nearby. Both the Romans and Belgae sought to avoid battle as they were low on supplies. Caesar ordered fortifications built, which the Belgae understood put them at a disadvantage. Rather than launching an assault, the Belgae disbanded and returned home where they could resupply and reassemble.

Caesar moved quickly to get ahead of the returning Belgae in the hope of defeating their forces in a piecemeal fashion. The city of Suessiones was besieged, and even though many Belgae were able to sneak into the city through the Roman lines, they quickly surrendered. Roman siege techniques were far more advanced than anything the Belgae had ever experienced. After the siege, many of the Belgae tribes surrendered, but not all had been cowed.

Julius Caesar Ambushed

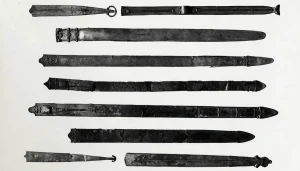

Gallic Sword and Sword Sheathe, La Tène III 120 BC-50 AD, via the British Museum, London

The Belgic Nervii, Atrebates, and Viromandui had not surrendered with the rest of the confederation, and amassing an army of 60,000 set a skilled ambush for the Romans. When the Romans arrived along the Sambre river, they began to set camp. Soon the approaching Nervii were detected. Julius Caesar dispatched some of his troops across the river to delay the Belgae while the rest of his forces fortified their position. This time, Caesar made a tactical blunder and failed to properly screen his forces. The Nervii took full advantage of this mistake, stormed across the river, and caught the Romans so off-guard that two legions were still absent from the battlefield.

The Romans were saved by their superior training and discipline, while Caesar’s mere presence helped raise morale. It was the eventual arrival of the remaining two legions, however, which eventually won the battle for the Romans. Caesar’s cockiness had nearly led to disaster for the Romans. The rest of the campaigning season was occupied with attacks on the Gallic tribes along the English Channel, which was a great success, and the Great St. Bernard Pass, which had to be abandoned due to the fierce resistance encountered. Caesar’s army was encamped for the winter amongst the Gallic tribes who were forced to provide them with food and shelter. As for Caesar himself, he once again returned to Cisalpine Gaul.

56 BC: Clearing The Gallic Coasts

Gallic Copper Alloy Coolus, La Tène III, 120 BC-50 AD, via the British Museum, London

While quartering his army amongst the Gauls certainly made things easier for Julius Caesar, it also created a lot of resentment. Roman officers sent to requisition grain from the Venti, a seafaring tribal confederation in modern Normandy and Brittany, were seized and imprisoned. The Venti then began fortifying their settlements, most of which could only be accessed by sea. Roman warships were not suited for operations in the rougher waters of the English Channel, and Caesar had to leave a large portion of his army behind to watch the Germans and Belgae. As a result, the Venti held the upper hand for most of the campaign.

Stymied, the Romans were forced to wait for the weather to calm down since there was no way to defeat the Venti without fighting a naval engagement. The battle was eventually fought off the coast of Brittany. It appears that the Venti possessed a far larger fleet, but their ships relied solely on wind power. The Roman ships were powered by oars, so they were able to pick up the Venti ships when the wind dropped. Additionally, the Romans also employed grappling hooks to shred the enemy sails and board their ships en masse. With their fleet destroyed, the Venti surrendered. As had now become his standard practice, Caesar had the Venti leaders executed and sold the rest of the tribe into slavery before moving to subdue the rest of the coastal tribes.

The Campaign Of Caesar’s Subordinates

Celtic Bronze Horse Figurine, 3rd-1st century BC, via Ancient Resource

While Julius Caesar focused his efforts on subduing the Venti, several of his subordinates were dispatched on campaigns of their own. Their contributions to Caesar’s Gallic Wars were operations in modern Normandy and Aquitaine. In Normandy, a coalition of the Lexovii, Coriosolites, and Venelli allied themselves to the Venti and attempted to cut off the Roman supply and communication lines. The Roman commander Sabinus entrenched his forces at the top of a hill. When the Gauls exhausted themselves after charging up the hill, they were easily defeated by Sabinus’ troops.

The campaign in Aquitaine was much more difficult as the Roman commander Publius Crassus, son of Crassus the Triumvir, was heavily outnumbered. After defeating one Gallic tribe on the march into the region, Crassus soon faced the Vocates and Tarusates. Long experience with Roman warfare had taught these tribes how effective guerrilla warfare would be against the legions. However, Crassus managed to locate their camp, which had only been fortified on one side. Taken by surprise and vigorously pursued by the Roman cavalry, the Gauls suffered an overwhelming defeat.

55-53 BC: Into Germania

Roman Short Sword or Dagger, 100 BC-200 AD, via the British Museum, London

Early in the spring of 55 BC, Julius Caesar’s soldiers massacred a large group of Germanic refugees who had crossed the Rhine during an armistice. This action was widely condemned in Rome and by the Senate. Hoping to restore his image, distract the public, and dissuade the Germans from launching raids into Gaul, Caesar embarked on a new series of campaigns. In only 10 days, Caesar’s men built the first bridge across the Rhine River. The Romans then marched across the bridge and spent a few days burning abandoned German villages. Satisfied with his demonstration of Roman power and receiving word that the Germans were massing an army, Caesar marched back into Gaul.

In 53 BC, Caesar would again repeat the process of bridging the Rhine, burning villages, and retreating without fighting a battle. The purpose of these incursions was to demonstrate to the Germans that the Rhine would not protect them from Roman power. They also served to bolster Caesar’s public image in Rome. Never before had a bridge spanned the Rhine, and never before had a Roman army crossed into Germania. With Caesar’s original five-year term as governor of Illyricum, Cisalpine Gaul, and Transalpine Gaul ending, he needed support in Rome to have his term extended.

55-54 BC: Crossing The Channel

The Battersea Shield, 350-50 BC; with The Waterloo Helmet, 150-50 BC, via the British Museum, London

Late in 55 BC, Julius Caesar also launched an attack across the English Channel into Britannia. According to Caesar, the Britons had aided the Venti in their fight against Rome during Caesar’s Gallic Wars. The first invasion nearly ended in disaster as the fleet was heavily damaged in a storm, and British resistance was fierce. As soon as it was feasible, Caesar withdrew his forces back across the channel. Although this invasion accomplished little, Caesar still received great accolades in Rome.

A larger invasion was launched in 54 BC and again nearly came to grief as a result of the rough weather in the channel. British resistance was fierce, but the Romans advanced much further into the countryside. The Romans were generally successful, but at the end of the campaigning season, Britannia was far from subdued. Caesar was also receiving word of mounting unrest in Gaul, so he was eager to return. Overall, Caesar’s invasions of Britannia accomplished little beyond furthering his political career back in Rome.

54-53 BC: A Winter War

Statue of Ambiorix, Tongeren, 1866, via Toerisme Tongeren

In Julius Caesar’s absence, discontent was growing amongst the Gauls as a result of poor harvests and the Roman occupation. This situation was exacerbated by Caesar’s practice of quartering his troops amongst the Gauls over the winter. Led by Ambiorix, the Eburones, a Belgic tribe in North East Gaul, launched a surprise attack on the Roman forces encamped in their territory. After surrounding the Roman camp, Ambiorix offered the Romans safe passage to one of the other nearby Roman forts. Following a bitter debate, the Romans choose to accept the offer. Once they had left their camp and entered a ravine, they were surrounded and massacred by the Gauls. This was the worst defeat suffered by the Romans during Caesar’s Gallic Wars.

Only a few Romans managed to escape the slaughter and spread the alarm to the other Roman forces. Meanwhile, more Belgic tribes rallied to Ambiorix’s cause and besieged the Roman camps in their territory. Some even called on the neighboring German tribes for support. Forewarned now of the uprising, the Romans were able to resist the Gallic attacks, though they were hard-pressed. Ultimately it was the arrival of reinforcements under Caesar that lifted the sieges.

53 BC: Eradicating The Eburones

Relief of the Gauls of Ambiorix fighting Julius Caesar’s Army by Jean-Charles Delsaux, ca. 1849, in Prince Bishop’s Palace Liege, via Ancient History Encyclopedia

Before turning his attention to Ambiorix and the Eburones, Julius Caesar first moved against the allied tribes. The Romans laid waste to fields, burned homes, drove off cattle, and took many Gauls as prisoners to ensure the continued good behavior of their families. It was at this time that Caesar crossed into Germania for a second time to dissuade the Germans from aiding the Eburones. When the Senate in Rome heard what had happened, Caesar faced severe criticism. Therefore, he swore to destroy the Belgic tribes.

Ambiorix and the Eburones were no match for the 50,000 professional soldiers that Caesar unleashed against them. In the resulting bloodbath, the Belgic tribes were slaughtered, and the Eburones ceased to exist. Despite the systematic slaughter, Ambiorix was never apprehended. He and his followers managed to escape across the Rhine into Germania, where they eventually disappeared and were never heard of again. Meanwhile, in Rome, the First Triumvirate had dissolved with the death of Crassus in Parthia and the marriage of Pompey to the daughter of Caesar’s main political opponent. Though far away in Rome, these events threatened the outcome of Caesar’s Gallic Wars.

52 BC: The Great Gallic Revolt

Perhaps hoping to capitalize on the political upheaval of Rome, a general revolt broke out in central Gaul when the Carnutes slaughtered all the Romans in their territory. This revolt would soon become the most famous event of Caesar’s Gallic Wars. The leadership of the revolt soon fell to Vercingetorix, who managed to unite many of the Gallic tribes. Realizing that he could not defeat the Romans in open battle he adopted a policy of scorched earth and sheltering behind fortified positions. His hope was to cut the Romans off from all sources of supplies and force them to retreat.

While many towns and villages were destroyed, the city of Avaricum was spared since its inhabitants refused to evacuate. When the Romans arrived to besiege the city, Vercingetorix carried out a guerilla campaign against them but did not enter the city. The siege of Avaricum lasted 25 days and required the Romans to undergo heavy labor while also facing serious shortages of foodstuffs. When they finally got into the city, the Romans slaughtered all but 800 of the city’s 40,000 inhabitants.

Gaul Ground Down

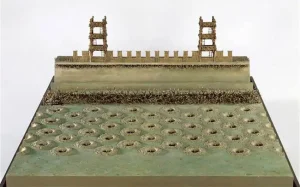

Model of Caesar’s fortifications in front of Alesia, via Musee D’Archeologie Nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Julius Caesar next pursued Vercingetorix to the city of Gergovia. Here the Roman assault was repulsed with heavy losses. Now unable to maintain the siege, Caesar withdrew and was pursued by Vercingetorix. When the Gauls were savagely beaten in a cavalry battle, they then withdrew to the city of Alesia, where Caesar finally managed to trap Vercingetorix and his army. Caesar built walls of circumvallation and contravallation around Alesia to prevent Vercingetorix from escaping or receiving reinforcements.

Before the walls were completed, Vercingetorix had managed to dispatch messengers who raised a relief army of 80,000-250,000. Yet with Vercingetorix trapped inside Alesia, there was no way for the Gauls to coordinate their attacks. The relief force eventually melted away and Vercingetorix was forced to surrender. He was executed at Caesar’s triumph in Rome in 46 BC. With the fall of Alesia, major fighting in Gaul ended; although mopping up operations of Caesar’s Gallic Wars would continue into 50 BC.

The Legacy Of Caesar’s Gallic Wars

Vercingetorix Before Caesar by Lionel-Noel Royer, 1899, in the Crozatier Museum, Puy-en-Velay, via the French Ministry of Culture, Paris

The conquest of Gaul as a result of Caesar’s Gallic Wars broke vast resources under the control of Rome. However, the conflict also hastened the end of the Roman Republic as Caesar’s rivals grew anxious about his power. Ordered to disband his army and return to Rome to stand trial, Julius Caesar instead chose to march on the city. The resulting civil war brought an end to the Republic and led to the creation of the Roman Empire.

Today, while historical sources describing Caesar’s Gallic wars are limited, they remain a popular topic in art, literature, and cinema. Leaders of the various Gallic, German, and British peoples who opposed Caesar are recognized as local heroes in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxemburg, and Britain. Though of course, none of them can compete with Julius Caesar who is today remembered as one of history’s greatest military commanders and whose conquest of Gaul is recognized as perhaps his greatest achievement.