Six Facets of Thoth, the Egyptian God

One of the most diversified and oldest venerated gods of Ancient Egypt, Thoth is a deity with many aspects.

One of the most significant gods in the everyday life of an ancient Egyptian was Thoth. Ancient Egypt was a world defined by one’s ability to survive in a hostile environment and their preparation for the afterlife. Thoth was important not only because he was the patron of scribes and the creator of hieroglyphic writing. He was also a key god for the Egyptians because his realm included subjects such as science, magic, mathematics, and the moon itself which influenced the lives of the commoners and the elites alike.

Thoth Was the Patron of Scribes and Sacred Texts

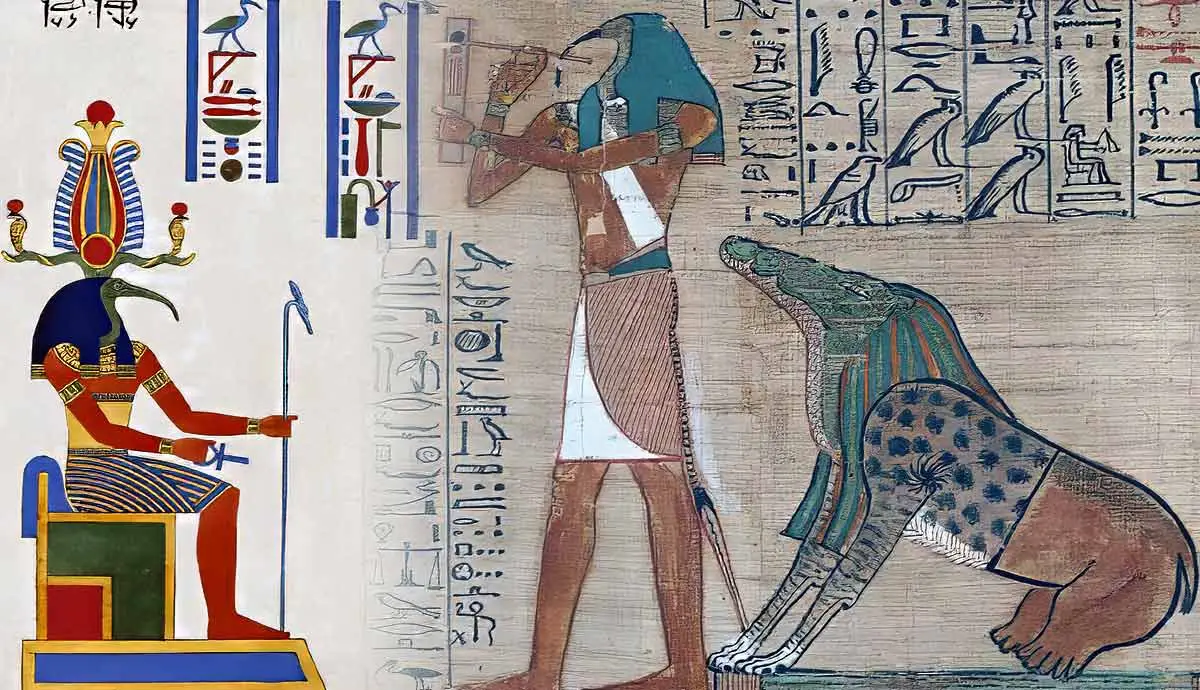

Thoth and Ammit in the Book of the Dead, Ani’s Judgment, 1250 BCE (19th Dynasty). Source: British Museum, London

Hieroglyphics engraved on stelas, temples, tombs, and papyri provide most of what academics know about ancient Egypt. Not only that, but hieroglyphics played an important role in the life of ancient Egyptians, from the recording of events, mythology, prayers and spells, and daily life. But just what are hieroglyphics?

The term hieroglyphics derives from the Greek meaning “sacred words”. According to ancient Egyptian belief, God Thoth was the creator of this intricate written language as well as the literary arts for both humans and gods. According to some myths, at the beginning of time, Thoth created himself through the power of language and, in fact, laid the cosmic egg that housed all of creation. Despite the importance of hieroglyphics, only the most affluent Egyptians (royalty, nobles, priests, and scribes) were capable of understanding the language’s complexities, and even then, mistakes were still made. As the creator of such a complex language, it was only right that Thoth became the patron and protector of scribes and sacred texts.

However, Thoth was not the only deity associated with writing and scribes. While Seshat, the occasional wife of Thoth, was in charge of maintaining the House of Life and documenting regnal years, Thoth was in the Hall of Truth in the afterlife. As the patron of sacred texts, Thoth was in charge of recording the verdict of the deceased at the heart-weighing ceremony. Additionally, Thoth had a residence in the afterlife known as the Mansion of Thoth. The Mansion of Thoth was not only Thoth’s home, but it was also a safe haven for journeying souls to rest and learn protective magical spells.

God of the Sciences

Striding Thoth faience figure, 332 – 330 BCE (Ptolemaic Period). Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The ancient Egyptians were unquestionably experts in several fields of science, including fermentation, medicine, mummification, engineering, and agriculture. In an environment that required continuous adaptation, science was to be taken seriously. Aside from monumental burial structures and temples, the ancient Egyptians are credited with having invented numerous tools. Wigs, locks, the use of papyrus and black ink, shadoofs, toothbrushes and toothpaste, the calendar and timekeeping devices are all examples of ancient Egyptian innovations that are still in use today.

As the god of sciences, Thoth was the creator of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and medicine and was credited with inventing the 365-day calendar. Notably, Thoth was not the only patron of medicine in ancient Egypt. Deities such as Sekhmet, Heka, and Isis were all patrons of medicine. However, medicine was associated with Thoth owing to the complexities of the subject and his role in safeguarding Isis during her pregnancy and restoring Horus’ stolen eye.

God of Magic

Thoth-Ibis and devotee statue attributed to Padihorsiese, 700 – 500 BCE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

In ancient Egypt, magic was a force intertwined with the world. It could be harnessed for healing and protection, curses and destruction, and the charging of special artifacts such as amulets and stelae. From birth to death, from eating to pregnancy, from the elite to the commoner, magic was always a part of an Egyptian’s daily existence. Thought to be as real as nature itself, magic was to be respected. Believed to be the embodiment of intelligence, the sciences, and the creator of language itself, Thoth was magic incarnate.

But why is Thoth regarded as a patron of magic while other deities, such as Heka (the deification of magic and magic itself), are also associated with it? Out of all the Egyptian deities, Thoth was believed to have contained the most Heka and, evidently, the advanced mind to appropriately yield it. According to the ancient Egyptian fable Setne Khamwas and Naneferkaptah, anyone who just read from Thoth’s book (the Book of Thoth), would understand the speech of animals and perceive the gods themselves.

Another example of Thoth’s magical prowess is when Thoth broke the curse placed on Nut, the Goddess of the Sky and Heaven by Ra, the God of Creation. In ancient Egypt, the Egyptian calendar consisted of 365 days a year, but it wasn’t always like that, apparently. According to the myth, Ra placed a curse on Nut that prevented her from conceiving children on any of the 360 days of the year (likely out of jealousy for Nut’s love of Geb). It wasn’t until Thoth added five more days to the year that Ra’s curse was broken, allowing Nut to be able to conceive during those five days.

God of Mathematics

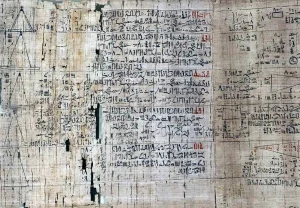

Rhind mathematical papyrus, 1550 BCE. Source: British Museum, London

Of all the branches of science, ancient Egyptians were well aware of the importance and the multifunctionality of maths. Everyone would have had daily exposure to maths, whether through warfare, agriculture, astronomy, economics, or architecture.

Despite the fact that Egyptian maths revolved around applied arithmetic and geometry, ancient Egyptians were able to solve complex problems. Although evidence of mathematics in Egypt is limited, two papyri show Egyptian mathematical skills: the Rhind papyrus and the Moscow papyrus. The Rhind papyrus demonstrates the use of fractions and problem-solving. The Moscow papyrus, on the other hand, depicts the volume of a truncated pyramid and the ancient Egyptians’ value of Pi equaling 3.16, which is similar to our current value of 3.14. Evidently, Egyptians not only practiced solving complex math problems, but they also inspired Greek mathematicians such as Thales and Pythagoras to visit Egypt and acquire techniques. Thoth, as the personification of knowledge and science, was believed to have invented maths.

As evidenced with his manipulation of Ra’s curse and control over celestial computations, recording of lunar observations and time, maths was merely another tool Thoth used in pursuit of earthly and divine knowledge.

God of the Moon

Thoth-baboon steatite statue with a lunar disc, 1292 – 1069 BCE. Source: British Museum, London

Very much like a plethora of Egyptian deities, Thoth, too, was associated with a celestial body. Emanating from a deep-rooted history within Egyptian mythology as early as Pre- and Early Dynastic (5000 -2686 BCE), Thoth’s mythological origins are conflicting and contradictory. Originally, Thoth was not a lunar god. However, Thoth’s role expanded to include maintaining cosmic order and harmony in addition to his already established mastery over magic and knowledge during the Middle Kingdom (2055 – 1650 BCE).

During the New Kingdom (1550 – 2070 BCE), Thoth was attributed the creation of the lunar calendar. The lunar calendar was used in ancient Egypt to manage agricultural cycles and measure the passage of time. Additionally, the phases of the moon were believed to have influence over magical ceremonies. Thoth, being a deity already associated with magic and now cosmic order, seamlessly transitioned into the position of a lunar god. To accentuate Thoth’s lunar aspect, iconographies of him would eventually be accompanied by a lunar disc and crescent, whether in the theriomorphic form of a baboon, an ibis, or an ibis-headed man.

Hermes Trismegistus: The Hellenistic Fusion of Thoth and Hermes

Marble relief of Hermes, 27 BCE – 68 CE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

After the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, the Greeks not only gained interest in Egypt but immigrated to Egypt. Eventually, the Greeks assimilated numerous Egyptian deities into their pantheon. Of the many assimilated deities, Thoth was one of the most important. As patrons of scribes, languages, and messengers in their respective pantheons, the Greeks pondered whether Hermes and Thoth truly roamed the world and shared divine knowledge with humanity. Even more so, the Hellenistic Greeks and Romans wondered if Thoth and the Greek god Hermes were one and the same. Through all the speculation and popularity of the new postulated connection between Hermes and Thoth, the well-known Hermes Trismegistus was born.

Eventually, authors of the ancient world would attribute a collection of ancient texts to Hermes Trismegistus himself, the Corpus Hermeticum, and other Hermetic texts. Although the texts spanned centuries, the Hermetic religion was popular and even challenged the rise of Christianity. Hermeticism still exists today and has directly influenced the doctrine of organizations such as the Golden Dawn, Freemasonry, and Rosicrucianism.