Searching the Sky: Prehistoric Maya Observatories in the Yucatán

Centuries ago, Maya astronomer-priests charted the heavens from huge stone observatories. From above the jungles of the Yucatán in modern-day Mexico, they carefully recorded the motions of the gods above: the sun, moon, stars and planets, and planned out their lives accordingly; when to sow, harvest, sacrifice, and make war – these were all decided by the heavens.

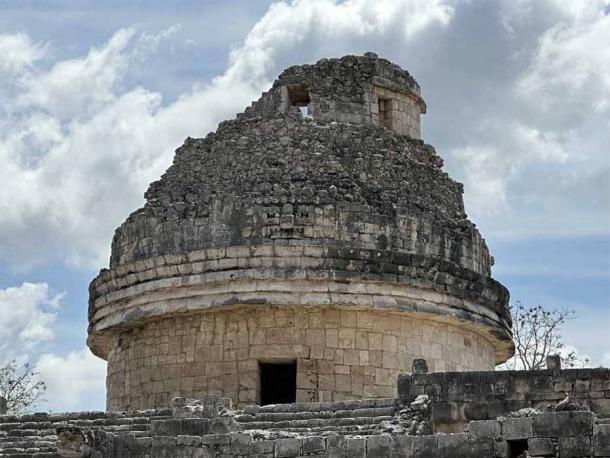

El Caracol, the Observatory- at Chichén Itzá. The building as a whole is aligned to the northerly extremes where Venus rises. (Image: © Jonathon Perrin)

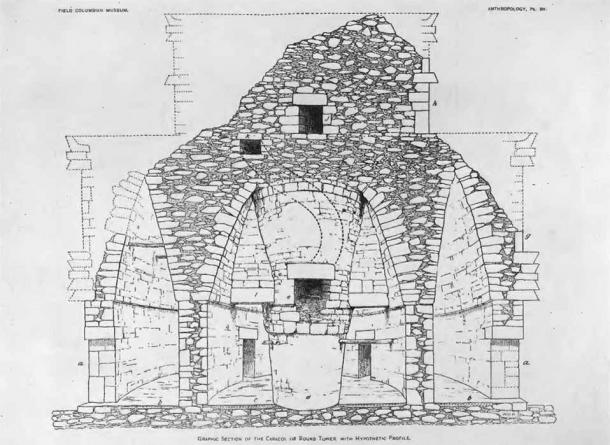

Covered in jungle and crumbling blocks, a ruined mound – that is how the ancient circular building known as El Caracol in the Maya city of Chichén Itzá, was first described by early explorers almost two centuries ago. Even then it was called an observatory, but only because its hemispherical-shaped ruinous state resembled contemporary European-style optical observatories. The irony is that this strange stone edifice actually did at one time function as an observatory for the ancient Maya astronomer-priests who ruled in Chichén Itzá. It did not however look like modern rounded observatories but was actually cylindrical with a flat roof, and was originally described as unattractive by early Europeans.

A high platform, reached by a narrow spiral staircase and surrounded by a stone wall riddled with precisely sized windows and holes, enabled these priests to observe at least 20 different astronomical alignments throughout the year. They did not use optical telescopes with lenses, but rather performed “naked-eye” astronomy from above the jungles of flat-lying Yucatán. By following the movements of the celestial bodies over the years, and carefully recording their changing positions, they created a form of agro-astronomy which let them precisely time when to prepare fields, and plant and harvest each crop, including the primary Maya staple – corn.

Updated interior plan of the Caracol, drawn by William H. Holmes in 1895. Clearly visible is the interior spiral stone staircase which would have allowed access to the second-floor viewing platform. Rupert, Karl, The Caracol at Chichen Izta (sic) Yucatan, Mexico, Carnegie Institution of Washington (1935).

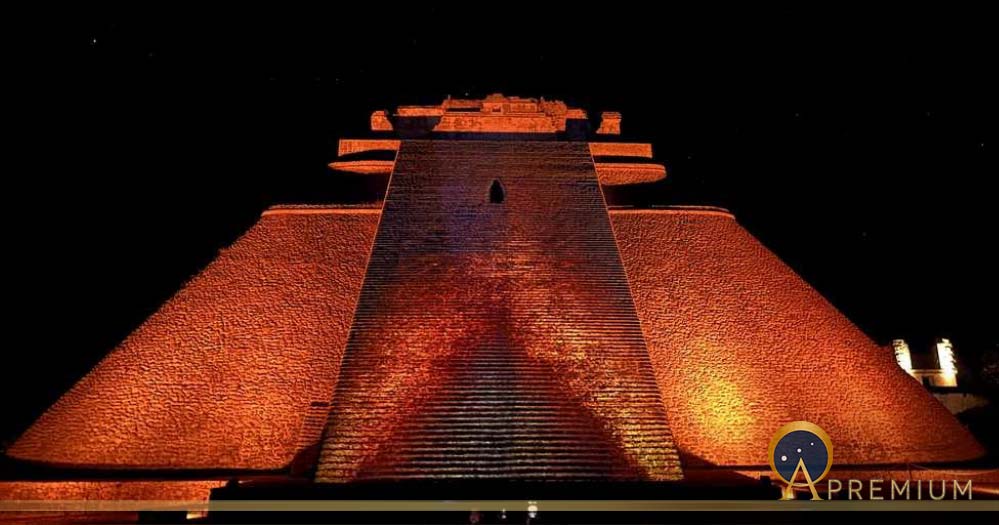

Not always uniform in plan, Maya observatories were in fact all quite unique, and represented different cultural traditions manifest in stone buildings. Some were pyramids, usually elliptical, such as the Pyramid of the Magician at Uxmál or the Observatory at Cobá, while others were actual circular buildings, such as the Round Temple at Mayapán or El Caracol at Chichén Itzá. Still others were quadrilateral, such as the Temple of the Seven Dolls at Dzibilchaltún.