Rome’s greatest enemy and worst nightmare, Hannibal Barca

A great general and a masterful tactician, Hannibal Barca is widely considered one of finest military leaders in history. He was the only man that Rome feared.

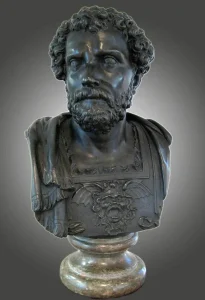

Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps, J. M. W. Turner, 1812, Tate Gallery; and Marble bust of Hannibal Barca, ca. 3rd century BCE, Palazzo del Quirinale, Rome, via Storia D’Italia

Nowadays, the military prowess and supremacy of ancient Rome is not questioned by the public. But that was not always the case. Throughout most of the third century BCE, Rome was engaged in a series of struggles with another powerful Mediterranean state — Carthage. The most brutal of those conflicts — the Second Punic War — put Rome in the greatest danger it ever faced. Rome eventually won, but it never forgot the man who had orchestrated its most shameful defeat: Hannibal Barca.

For nearly two decades, Hannibal fought the Romans. He invaded Italy and forced Rome to battle for its very survival. Every army sent against him perished, with Hannibal employing a set of stratagems and tactics to outmaneuver and defeat his superior foe. However, without the necessary support from Carthage, and with Rome borrowing his tactics in Spain and North Africa, Hannibal was ultimately defeated. Forced to flee from the Romans, Hannibal spent his last years at the various courts of the Hellenistic kings. In death, he outmaneuvered his foes once again, by taking poison before the Romans could catch their worst nightmare.

Hannibal Barca: The Early Years

Marble bust of Hannibal Barca, ca. 3rd century BCE, Palazzo del Quirinale, Rome, via Storia D’Italia

When Hannibal’s father, Hamilcar Barca, was preparing to leave for Spain, he took his nine-year-old son to a temple in Carthage and had him swear an oath of eternal hostility towards Rome. This famous episode perfectly reflects Hannibal’s character, and his lifelong mission: to defeat and humiliate the upstart Republic and restore Carthage to greatness. But we should not forget that this story was recorded by the winning side. There are no surviving Carthaginian sources. Polybius, the Greek historian who chronicled Hannibal’s life and his role in the war, was, after all, in the service of Rome.

Despite the obvious bias, there might be a grain of truth to this story. Hannibal’s house, the Barcids, was one of the most notable families from Carthage. They were also a fierce enemy of Rome. Hannibal’s father, Hamilcar, served as a prominent commander during the First Punic War.

The twenty-year-long war ended with Carthage’s defeat, and the loss of most of its overseas territories, including the wealthy island of Sicily. Furthermore, Carthage had to pay enormous war reparations to Rome. To prevent the ruin of his country, Hamilcar Barca decided to expand Carthage’s influence and territory in the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal). The area was rich in resources, and Iberian gold and silver mines could be used to pay the reparations to Rome and fund Carthage’s military.

The Oath of Hannibal against the Romans, Claudio Francesco Beaumont, ca. 1730-1766, Mussée des Beaux Arts, Chambéry, via Images D’Arts

Hamilcar left on this mission in 237 BCE, accompanied by his young son. Many years would pass before Hannibal would see his home city again. For nine years Hamilcar campaigned in Iberia, expanding Carthage’s reach deep into the peninsula. Hannibal’s childhood was spent in a military camp, and by the age of 18, the youth already commanded the troops. The death of his father in 228 BCE and his brother seven years later, left Hannibal in command of all the Carthaginian forces in the Iberian Peninsula. He was only 26.

Hannibal swiftly consolidated power in Spain, making the coastal city of Cartagena (New Carthage) the base of his family’s military and economic power. The rapid unchecked expansion of the Barcid influence in the Peninsula, however, worried the Senate of Rome, which decided to act. To curb Hannibal’s power in the region, Rome allied themselves with the city of Saguntum.

According to an earlier treaty, the Ebro river acted as a demarcation line between the Roman and Carthaginian sphere of influence. Saguntum was far south of the Ebro river, and Hannibal considered this a breach of a treaty. He laid siege to the city and captured it after eight months in 219 BCE. Rome jumped at this opportunity demanding that Carthage turn Hannibal in. And so the Second Punic War began.

Crossing The Alps

Hannibal crossing the Alps, Nicolas Poussin, ca. 1625-1626, private collection, via Christies

Hannibal was well aware of the unfavorable strategic situation of Carthage. Roman naval supremacy prevented a direct attack from the sea, while the Roman legions greatly outnumbered his army. A lesser commander would have opted for a defensive strategy, making the Ebro a formidable bastion. But Hannibal Barca was a different sort of leader. In fact, he was a military genius, and he was about to show his brilliance to the world, in the most striking way possible. Hannibal would attack the enemy on his home turf, bringing the war to Italy.

In the late spring of 218 BCE, Hannibal and his army crossed the Ebro and moved northwards. The journey was not an easy one. Following his victory over the hostile tribes in the Pyrenees, Hannibal detached some of the troops to guard the passes and protect his rear. According to our sources, Hannibal entered southern Gaul at the head of 40,000 infantry, 12,000 horsemen (including the famous Numidian cavalry), and 38 war elephants. Instead of fighting the Gauls, Hannibal made a deal with the local chiefs and crossed the Rhone before the Roman army could check his advance. Successfully evading the Roman force, and outmaneuvering the hostile natives, in late October, Hannibal reached the foothills of the Alps.

Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps, J. M. W. Turner, 1812, Tate Gallery, London

Aware that the enemy had escaped, the Romans returned to Italy to prepare their defenses for the next spring. Only a madman would dare to cross the Alpine passes this late in the year, they thought. Unfortunately for the Romans, Hannibal of Carthage was a madman. His Alpine adventure became the stuff of legend. Before the crossing, the army abandoned all its siege engines and part of its supply train, before beginning its ascent. The crossing was long and arduous. The army had to brave severe winter conditions, harsh terrain, avalanches, blizzards, and subzero temperatures. All the while the column was facing attacks from the hostile tribes who lived in the mountains. Food was scarce, and some soldiers were close to mutiny. But Hannibal did the impossible, and seventeen days later, the front of the battered column emerged in the Po valley.

Prelude To Cannae

Hannibal in Italy, detail from the fresco in the Hall of Hannibal, Jacopo Ripanda, ca. 1510, Musei Capitolini, Rome

Hannibal Barca did the impossible. He crossed the Alps and reached Italy. However he lost almost all his elephants, and what remained of his army was in bad condition. Luckily for the Carthaginian general, the local tribes were revolting against Rome, and through a mix of diplomacy and force, Hannibal’s army was quickly replenished and ready for battle. The sudden appearance of the hostile force at their doorstep shocked the Romans. However, they were quick to act and they sent General Scipio (father of Scipio Africanus) to intercept them. In November 218 BCE, the two armies met at the Ticinus River. The Romans were defeated and Scipio, badly wounded, was forced to retreat. This was the first of Hannibal’s many triumphs in Italy, which would bring Rome to its nadir.

Ticinus was a minor victory for Carthage, but it was a portent of things to come. Trebia, a month later, was a major triumph. Many Romans were killed fleeing for their lives, and more drowned in the icy river. It is believed that the Roman army suffered 20,000 to 30,000 casualties, compared to a few thousand on Hannibal’s side. The Battle of Trebia was a resounding success for Hannibal, as news of his victory spread quickly among the local tribes, who joined Hannibal’s cause. A new victory soon followed.

Aerial view of Lake Trasimeno, Umbria, via SummerinItaly

In spring 217 BCE, Hannibal again surprised the Romans, who blocked two of the main routes through the Apennines leading south. Instead, Hannibal led his army through the Arno Valley, a marshland traditionally considered impassable. The march was not without a loss. Many soldiers drowned in the marshes or died of infection, and Hannibal himself lost sight in one eye. At the shores of Lake Trasimene, Hannibal Barca annihilated the pursuing Roman army in what is considered the largest and most successful ambush in military history. More than 15,000 Romans were killed, and 15,000 were taken prisoner. The road to Rome was now open.

Cannae, A Masterpiece Painted In Roman Blood

The Death of Aemilius Paulus at the Battle of Cannae, John Trumbull, 1773, The Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

Despite the military disaster, Rome was unwilling to surrender. The Senate appointed a dictator, Quintus Fabius Maximus, to save the Republic. Fabius became known as a delayer (cunctator), who avoided pitched battle, and employed a scorched earth policy, which deprived Hannibal’s army of vital provisions. Although this strategy worked, it was not popular with the Senate, who wanted a quick victory. It was even less popular with the aristocrats whose huge estates in Southern Italy were being looted by Hannibal’s forces.

The decision was made; the upstart Carthaginian had humiliated the Romans for too long, and he had to be eliminated. In 216 BCE, Fabius was removed from his post, and the Republic elected two new consuls: Terentius Varro and Aemilius Paulus. They were given a joint command of a massive army of around 80,000 men. The largest army Rome had ever fielded had one task – to stop Hannibal.

Hannibal was aware that the Romans were coming for him and prepared accordingly. To provoke the Romans to attack, he captured an important supply depot near Cannae, a settlement on the Adriatic Coast. On August 2nd 216 BCE, the two armies met outside of Cannae. Varro, who was in command of the army that day (the consuls alternated command daily), packed his legionaries together tightly in order to smash the Carthaginian foot soldiers in the center of their line. Hannibal anticipated this move and used Varro’s deep formation against him. He placed light infantry in the center of his line and veteran heavy infantry on the flanks. The result was a maneuver that is still taught in the military academies to this day.

Hannibal, featuring Hannibal Barca counting the rings of the Roman noblemen slain at Cannae, Sebastian Slodtz, 1704, Louvre, Paris

When the Romans advanced, the center of Hannibal’s infantry withdrew, while the flanks held firm. Slowly, Hannibal’s line took on a crescent shape, drawing more and more legionaries to attack the center. What the Romans did not realize, however, was that they were being lured into a trap. Tens of thousands of the Roman soldiers found themselves encircled by the enemy. The already tight formation became even tighter, to the point that many Romans were unable to swing their swords. The Carthaginian cavalry delivered the last blow. Having chased away the Roman horsemen from the battlefield, it returned and charged at the Roman rear. The Roman soldiers at the front hardly realized their perilous position. And then it was too late. By the time darkness fell, there was nothing left of the Roman army. It had been utterly annihilated.

One of the consuls, Aemilius Paulus, was killed in the fighting, while Varro and the few survivors fled the field of battle. Hannibal’s brother Mago demonstrated the scale of the victory by toppling a large urn filled with gold signet rings in front of the Carthaginian Senate, each ring taken from the hand of a Roman nobleman, slain in the carnage of Cannae. The Battle of Cannae was the worst defeat suffered by Rome in its history, both as a Republic and later as an Empire. Writing in the late fourth century CE, Ammianus Marcellinus would call emperor Valens’ defeat at Adrianople, the worst Roman military disaster after Cannae.

From Victory To The Defeat

Print of Hannibal of Carthage, John Chapman, 1805, The British Museum, London

The victory at Cannae was the high watermark of Hannibal’s campaign in Italy and the apex of his military career. It was also the beginning of his troubles. Rome was utterly defeated, its powerful army was gone, and most of the high-ranking commanders perished in two years of successive defeats. The core of the Republic, the Apennine peninsula, was devastated, and fell largely out of Roman control. But the Republic was resilient. When Hannibal offered to negotiate peace terms, the Senate refused. It was a risky move. After Cannae, Rome was in full panic. Hannibal ante portas (Hannibal is at the gates) was a byword of the day. Fortifications were hurriedly repaired, while sentries observed the horizon, expecting the arrival of a huge enemy host.

But Hannibal never arrived. We do not know why Hannibal Barca did not march on Rome. Was he still hoping that peace could be arranged? Hannibal’s troops were victorious, but they were also exhausted and in a dire need of rest. Rome’s vaunted Aurelian walls were still centuries in the future, but the city’s defenses presented a formidable obstacle for an army that lacked siege equipment and was not prepared for that lengthy endeavor. Most importantly, despite all his successes, Carthage was reluctant to send any support.

Hannibal’s family was only one of several powerful factions in the Carthaginian Senate, who considered the defense of the Iberian Peninsula, with its gold and silver mines, more important than Hannibal’s Italian adventure. The only attempt to reinforce Hannibal failed, when the Romans defeated the relief army in 208 BCE. Instead of much-needed troops, Hannibal received the head of their commander, his brother Hasdrubal. Thus, Hannibal was forced to replace his veteran units with much less experienced and motivated mercenaries from southern Italy.

Bronze bust of Scipio Africanus found in Villa Papyri at Herculaneum, 1st century BCE, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, via Pinterest

Rome too, changed its strategy after Cannae. Instead of directly confronting Hannibal, the Romans directed their efforts towards the center of Barcid power – Spain. The survivor of Cannae, Publius Scipio (known later as Africanus), was put in command of the Roman armies, and sent overseas, while in Italy, the Romans returned to the Fabian tactics of containment, avoiding open battles and engaging in guerilla warfare.

Although undefeated, Hannibal could only helplessly watch Scipio’s legions driving the Carthaginians out from Spain. Meanwhile, Roman strength in Italy gradually increased, with allies abandoning Hannibal one by one. Finally, in 204 BCE, Scipio landed in North Africa, bringing war to Carthage’s doorstep. Fearing the fall of the capital, the Carthaginians recalled Hannibal.

The Later Years

Battle of Zama, Giulio Romano, last third of the 16th century, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

The final episode of the Second Punic War unfolded on October 19th 202 BCE, on the plains of Zama. Hannibal was put in command of a large army. He could count on the veterans from the Italian campaign, as well on his 80 war elephants. Hannibal intended to use the elephants to shock the Romans. But this time, Hannibal of Carthage faced a new enemy who had studied his tactics, and had developed a way to counter them.

When the elephants charged at the Roman lines, the Romans opened gaps in their ranks, allowing the ferocious beasts to pass through the corridors. Some of the animals lost their handlers, running amok among the Carthaginian lines, trampling the unfortunate soldiers. Taking the initiative, Scipio ordered his Numidian and Roman cavalry to attack the Carthaginian horsemen protecting Hannibal’s flanks. When Scipio’s cavalry returned from the chase, they hit the enemy infantry (locked in a struggle with the Romans) from behind. The result was a decisive victory for the Romans.

After Zama, Carthage was reduced to an inferior status. Besides huge war reparations, Carthage had to renounce all its overseas possessions, and could not take military action without the approval of Rome. Despite his defeat, and the loss of his power base in Spain, Hannibal Barca retained his influence in Carthage. His military successes secured him powerful supporters, and for a few years Hannibal played an important role in Carthaginian politics. Rome, however, was not ready to forget the humiliation suffered in the war. The Republic’s envoys continued to call for Hannibal’s extradition, threatening another war. Hannibal was now forced to leave Carthage a second time. This time for good.

The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire, J. M. W. Turner, 1817, Tate, London

For a few years, Hannibal Barca served as the chief military advisor at the Seleucid court of Antiochus III. His hopes of striking Rome once again were dashed when the Romans defeated Antiochus at Magnesia in 189 BCE. Hannibal was now on the run. He may have fled to Crete or taken up arms with rebel forces in Armenia. His last military action was in the service of king Prusias I of Bithynia, who fought against the kingdom of Pergamon, a Roman ally. There, Hannibal won his last victory, defeating Pergamon’s fleet in a naval battle. The Romans, however, intervened, demanding Bithynia hand over Hannibal. Backed into a corner, Hannibal of Carthage outmaneuvered his foe for the last time. As the Roman legionaries were closing in on his home, the old general committed suicide by drinking poison. He was 66 years old.

Hannibal Barca: The Greatest General Of The Ancient World?

Bust of Hannibal Barca, possibly owned by Napoleon, François Girardon, 17th century, Museum of Antiquities, University of Saskatchewan

Carthage outlived Hannibal by only 35 years. Determined to eliminate its former rival once and for all, in 146 BCE Rome went to war with Carthage for the third time. This time, the legions captured the city, burning it to the ground. Rome was now the master of the Mediterranean, and on its way to becoming an ancient superpower.

Hannibal’s ghost, however, continued to haunt the Romans. Hannibal ante Portas remained a catchphrase whenever calamity befell a Roman citizen. More importantly, Hannibal’s unbroken chain of victories during his Italian campaign caused a change in Roman military strategy and doctrine. The long and protracted warfare altered the usual Roman conscription strategy; they gradually moved from using citizen-soldiers to a professional standing army, and moved from loyalty to the Senate and the Republic, to loyalty to their commanders, and ultimately, the emperor.

Hannibal of Carthage was perhaps Rome’s worst nightmare, but he was also their greatest teacher, reshaping directly or indirectly their military and society. The greatest Roman writers from Livy to Ammianus Marcellinus, admired Hannibal. Centuries after the great general’s death, Emperor Septimius Severus made him a new tomb, coated in marble, which became a place of pilgrimage for centuries. The Romans built statues to their greatest enemy, partly as evidence of their ultimate victory, partly as a sign of grudging respect.

The strategy and tactics employed by Hannibal have been mandatory study for every great commander, from Julius Caesar, to Napoleon Bonaparte, to George S. Patton. The double envelopment at Cannae that spelled the disaster for the Romans is still taught at the most prestigious military academies as a textbook example of a “perfect battle.” Hannibal was defeated by Rome, but his legend lives on.