Roman Republic: Commoners against Nobility

The Roman Republic was greatly innovative, forerunning current systems of government. But what happened when Rome’s masses turned against the system?

Following the overthrow of Tarquin the Proud, the last monarch of the Roman Kingdom, the citizens of Rome embarked on one of the most remarkable political experiments of the ancient world. The complex political structure of the Roman Republic (c. 509-27 BCE) was designed with the ideal intention of preventing tyrannical one-man rule. It introduced checks on power and was meant to impede its abuse and accumulation among overly ambitious individuals. Yet, the story of the Roman Republic is one of regular crises and strife. The divide between its elite and disgruntled lower social classes was a constant thorn in its side. Attempts to effect positive change, as seen with the renowned reformer Gracchi brothers, were met with increasingly intense resistance.

Was the Roman Republic Fair?

Roman Forum, by Anonymous, 17th century, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

From the outset, the harmony of the Roman Republic was impaired by the wealth and power hoarding of Rome’s aristocratic class, the patricians, and the struggle of the majority commoners, the plebeians, for their respective share. The patrician-plebeian distinction was based less fundamentally on wealth than it was on birth and status, but an acute inequality persisted between the two.

To some extent, the Republic’s government resembled that of a democracy. At its helm were two elected consuls and various public officials, or magistrates, who served one-year terms and were elected by citizen males. The supreme representation of the Roman people were the legislative assemblies through which citizens were organized and collective decisions made. The functions of the state, once all held by the king, were effectively divided up.

Yet, in practice, the Roman Republic was an oligarchy. The Senate, which served as an advisory body and lacked legislative powers, was entirely dominated by influential patricians and so enjoyed extensive authority, particularly over state finances. The patricians also monopolized the consulship and magistracies. The assemblies, too, were inherently biased. The most powerful was the Centuriate Assembly, which declared and rejected wars, enacted laws, and elected consuls and other officials. It was initially subdivided into five classes composed of military representatives of the Roman citizenry, but the voting process was skewed in favor of the first classes into which the wealthiest and most influential citizens were enrolled. Consequently, the largest and poorest lowest classes had little to no influence.

The result was that most of Rome’s citizens had little political sway and were limited by a narrow selection of elite politicians. The plebeians were not unaware of their unprivileged status. Less than twenty years into the Republic’s foundation, the situation boiled over.

Setting Matters Straight: People’s Power in the Roman Republic

Curia Hostilia in Rome (one of the original Senate meeting places), by Giacomo Lauro, 1612-1628, via Rijksmuseum

Throughout the first half of the Roman Republic, the plebeians protested their grievances and unacceptable patrician provocations in the form of a peculiar kind of strike. They would jointly abandon the city and move to a hill outside the walls, notably the Mons Sacer or the Aventine.

The first plebeian ‘secession’ (495-493 BCE) arose when the patrician-dominated government refused debt relief for the heavily burdened plebeians who were adversely affected by wars with neighboring tribes. The lenders were patricians who subjected their plebeian debtors to violent punishments and even enslavement when they failed to pay. The departure of the vast majority of Rome’s inhabitants would have been a fatal blow. The plebeians were Rome’s farmers, soldiers, artisans, shopkeepers, and laborers. Not only could they virtually empty the city, but they could bring its economic functioning, and so too the patricians, to a halt.

Unsurprisingly, concessions came through debt relief and notable compromises. The Senate agreed to the formation of a distinct Plebeian Assembly serving the plebeians. It also acceded to the formation of the office of the tribunes of the plebs, which would gradually increase from two to ten. Their principal duty was to safeguard plebeians and their interests, and the greatest tool at their disposal was the right of veto against the proposals of other magistrates. The plebeians had acquired significantly more political agency.

Naturally, this was not so popular with all patricians, whose indignation could become ruthless. As the historian Livy recounted, the price of corn had risen with the plebeian abandonment of the fields, and famine followed. Once grain had been shipped in from Sicily, the patrician general Coriolanus vengefully suggested that plebeians should receive grain at the former price only if they renounced their newfound powers.

Legal Equality

The Laws of the Twelve Tables, by Silvestre David Mirys, c. 1799, via Wikimedia Commons

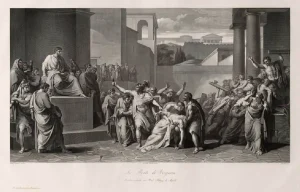

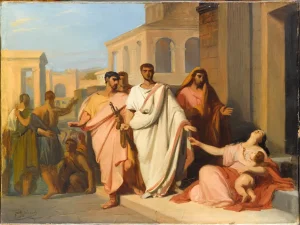

The plebeians had also been demanding that Rome’s laws be publicized to ensure a common legal equality between the two classes. Therefore, for a year, normal political procedures were suspended and ten men (decemviri) were appointed to collect and publish Rome’s laws in the ‘Twelve Tables’. Another set of decemviri were appointed the following year to finish the job, but they opted to produce controversial clauses. Most notably, the ban on intermarriage between patricians and plebeians. Their behavior, too, induced outrage. When one of the decemviri, Appius Claudius, apparently demanded relations with the betrothed plebeian Virginia to no avail, his attempt to grab her in the Forum saw her maddened father stab her to death to, as he perceived it, set her free. A second secession came by 449 to demand their resignation, and a third in 445 to repeal the ban on intermarriage.

The Death of Virginia, Vincenzo Camuccini, 1804, via National Gallery of Art Library

Pivotal plebeian victories trickled in and the patrician monopoly on government was increasingly severed. In 367, one of the consulships was finally opened to plebeians, and in 342, following a fourth secession, both consulships could be occupied by plebeians. The year 326 saw the abolishment of debt slavery, and so plebeian liberty as citizens was secured.

The plebeians marched out one final time in 287, incensed by unfair land distribution. The result was decisive. To quell the strife, the dictator Quintus Hortensius passed a law that stipulated that the decisions of the Plebeian Assembly were to be binding for all Romans, patricians and plebeians alike.

The playing field was evened. The Roman Republic became somewhat fairer for plebeians who used their natural benefit to their advantage — their numbers. A new elite was now forming, composed of patricians and the wealthiest plebeians. Though the historicity of this era is plagued by certain inconsistencies and blank spots, it was clearly defined by popular power and a struggle for freedom of political participation by the Roman masses.

In Come the Gracchi Brothers

The Gracchi, Eugene Guillaume, 1853, via Wikimedia Commons

It took more than a century for social strife to gravely threaten Rome’s stability again. Rome had been busy with its relentless territorial expansion in Italy and throughout the Mediterranean and its huge wars with Carthage and the Greek kingdoms. The Roman Republic was evolving into an empire. Its victories, however, did not come without a price, something that the reformer Gracchi brothers had observed.

The Italian countryside was in an unenviable state. Gone were the small, peasant farmers who had been displaced by destructive wars on Italian soil and the demand for overseas conflicts. The land was now dominated by large estates owned by wealthy landowners, funded by plundered wealth, and tended by slaves. Many now-landless peasants had little else to do than move to Rome.

The Great Reformer: Tiberius Gracchus

The Death of Tiberius Gracchus, Lodovico Pogliaghi, 1890, via Wikimedia Commons

That is, at least, the scenario that Tiberius Gracchus had painted to secure his election as tribune in 133 BCE. Indeed, it is not clear just how extensive or hyperbolic this problem was. Still, upon election, Tiberius sought to redistribute the ager publicus (the ‘public land’ of Rome that was leased to citizens) more equitably. He proposed limits on the amount of land farmers could possess and the reallocation of the expropriated to landless farmers.

This was too radical for his expected foes in the Senate, the fortress of the landowning aristocracy. The Senate requested another tribune, Marcus Octavius, to veto Tiberius’ proposal in the Plebeian Assembly, a cruel irony of the tribune’s intended purpose. Yet Tiberius had amassed popular support, and so had the assembly vote Octavius out of office and manhandle him out of the meeting. In came the accusations of tyranny and aspiring to kingship. He even used the money granted by the recently deceased King Attalus of Pergamum, who bequeathed his kingdom to Rome, to pay for land commissioners to survey and parcel the land, seeing as the Senate would not grant funds.

The following year, when Tiberius announced he was standing for a second term, the Senate blocked his candidature. He took to the Forum with a crowd of supporters, where he was met by a mob led by senator Scipio Nasica. Tiberius and hundreds of his supporters were battered to death, their bodies discarded into the Tiber River. It was an unprecedented violent episode in Roman politics.

Throngs of destitute landless people in an agrarian society was a recipe for disaster. Tiberius was well-positioned to rouse popular anger, regardless of whether he was a genuine reformer or crafty demagogue. The old discord between the people and the aristocracy was now morphing into a new factionalism. The populares, meaning ‘for the people’, stood for the cause of the commoners. In opposition were the optimates, the ‘best men’ of the aristocracy, who perceived themselves as the most prudent guardians of the Republic.

Unfinished Business and Resistance: Gaius Gracchus

The Departure of Gaius Gracchus, Pierre Nicolas-Brisset, 1840, via Musée d’Orsay

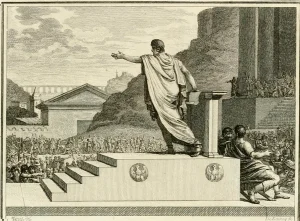

Tiberius was eliminated, but soon after came the second of the Gracchi brothers, Gaius, who became tribune in 123. He set straight to work. He continued Tiberius’ land reforms. He passed a law to provide citizens in Rome with grain below the market price. He passed control of the courts from senators to the equestrians (knights) so that it was easier to condemn senator governors who extorted provincials. His anti-senatorial sentiment extended to his public behavior too. As the Greek historian Plutarch recalled, when addressing audiences in the Forum, he would turn his back to the senate house despite it being customary to face it. His message was clear. The Roman Republic was its people, not its elite.

The pursuit of Gaius Gracchus, 1900, via archive.org

Yet it was when he planned to extend Roman citizenship to the Latins (the people of Latium surrounding Rome) and a more limited form to other allies that he seemed to fleetingly unite the people and the aristocracy in their outrage. The idea of being outnumbered by non-Romans and having to share their privileges as citizens was widely unpopular. Alarmed by the increasingly violent militancy of Gaius’ supporters, the Senate mobilized and supported the tribune Livius Drusus, who enticed the Romans away from Gaius with his own promises. Gaius’ fate came in 121 when he attempted a third term, killed along with other followers in a mob ambush on the orders of the consul Lucius Opimius. Some 3,000 other Gracchi supporters would later be put to death by decree of the Senate under the pretext of state security. The Gracchi brothers, champions of the liberty and rights of the Roman masses, met equally tragic fates.

The Roman Republic: A Never-ending Impasse

Gaius Gracchus, tribune of the people, by Silvestre David Mirys, 1799, via archive.org

Be it patricians vs. plebeians, Senate vs. tribunes, optimates vs. populares, the dispute between the aristocracy and the people metamorphosed and intensified with time. The Roman Republic was constantly marked by the incompatibility of their views on governance and the unwillingness of the aristocracy to concede power and wealth. Yet, corruption scourged Rome everywhere. Even tribunes such as Marcus Octavius and Livius Drusus could abuse their duties for aristocratic interests.

The fracture between the optimates and populares would come to condition the events of the final chaotic century of the Roman Republic. The civil war between Julius Caesar, who aligned with the populares, and Pompey’s optimates; Caesar’s infamous assassination; the end of the Republic and the onset of the emperors. The assassinations of the Gracchi brothers had set a precedent of violence. Ultimately, the price to pay for stability was liberty.