Reclaiming Iberia: The Magnificent Story of Spain’s Reconquista

The Reconquista, a pivotal chapter in medieval European history, represents the centuries-long struggle in the Iberian Peninsula as Christian kingdoms sought to reclaim their territories from Islamic rule. Beginning in the early 8th century, the Umayyad Caliphate’s conquests had established Al-Andalus, a flourishing Islamic state, while Christian enclaves persisted in the north.

This historical process, fraught with religious fervor, political intrigue and military campaigns, culminated in 1492 with the capture of Granada and the fall of Islamic Spain. The Reconquista’s influence extended far beyond its time, shaping the course of European history and exemplifying the intricate interplay of faith and power.

Backdrop to the Reconquista: The Islamic Conquest of Spain

The Reconquista’s roots can be traced back to the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century. In 711 AD, the Umayyad Caliphate, led by General Tariq ibn Ziyad, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar, and swiftly conquered the Visigoth kingdom of Hispania. The invaders, largely Berbers and Arabs, brought with them the religion of Islam and introduced a new era to the region.

Under Islamic rule, the Iberian Peninsula, known as Al-Andalus, experienced a period of cultural flourishing. Cordoba, in particular, emerged as a vibrant center of learning and sophistication, boasting impressive architectural achievements as evidenced by its Great Mosque. Al-Andalus witnessed the harmonious coexistence of Muslims, Jews and Christians, fostering intellectual exchange and translating ancient texts into Arabic.

Modern-day image of the Great Mosque in Cordoba, built under Islamic rule in the 8th century was converted into a Catholic cathedral after the Reconquista of Cordoba in 1236. (rabbit75_fot / Adobe Stock)

Growing Resistance: The Birth of the Reconquista

Unsurprisingly this harmonious coexistence was doomed not to last. Christian resistance began almost immediately and in 718 AD Pelayo, a Visigoth noble who hailed from Asturias in the far North, led a small Christian force to victory over the Muslims at the Battle of Covadonga. While this battle was relatively small in scale, it marked the symbolic beginning of the Christian effort to reclaim the Iberian Peninsula.

Pelayo’s victory led to the establishment of the Kingdom of Asturias, centered in the mountainous region of the north. Over the years, this fledgling Christian kingdom grew in strength and size, as other Christians from various parts of Al-Andalus sought refuge in Asturias.

Over the next few hundred years Asturias would occasionally make peace with its Muslim neighbors whenever another enemy rose up. While Asturias eventually ceased to be in 924 AD its existence signified the beginning of the Christian fight to retake their homeland from Islamic rule.

15 Facts About the Moors You’ve Probably Never Heard

Aeons of Battle: The 5 Longest Wars in History

The Muslims never conquered all of Spain, and by the 11th century AD, the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain were ready to take back what had been lost four hundred years previously. Their timing was immaculate, the Cordoba Caliphate had been wracked by civil wars in 1031 AD and was severely weakened.

There were five states in all; Aragon, Catalonia, Castile, Leon and Navarre, as well as Portugal which had claimed independence in the 1140s, that began to fight the Muslims. As the fighting spread other smaller kingdoms began to appear. Some of these were set up by men looking to use all the turmoil to their own advantage.

The best example of this is Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, a Castilian knight who managed to set up his own kingdom based out of Valencia in 1094 AD. While his kingdom was short lived, it showed how successful opportunists could become during this period. It wasn’t just Christians expanding their influence, however.

This fledgling Christian resistance against the Muslims wasn’t exactly organized yet (that would come much later) and these Christian kingdoms spent as much time fighting each other as they did the Muslims. It wasn’t until 1085 AD that the Reconquista, which had begun with Pelayo in 718 AD, had its next major success.

This came in the form of King Alfonso VI of Leon and Castile who managed to retake Toledo, which had once been the capital of Christian Spain, from the Muslim invaders. This major win inspired Pope Urban II to get involved and begin backing the idea of a “reconquest.” In 1096 he began offering spiritual rewards to anyone who fought to retake the Iberian Peninsula and at some point between 1114 and 1123 AD his successor, most likely Pope Paschal II, gave the peninsula full equality with the Holy Land.

This isn’t to say all the fighting in Spain was motivated by religion. The Pope may have been offering spiritual rewards, but for a long time fighters were motivated by more earthly rewards, in the form of political power and treasure. The Muslims had huge gold reserves that they had taken from Africa’s Gold Coast and brought to Spain. This was a fact that the rest of Europe hadn’t failed to notice.

At which point the fighting in Spain transformed into religiously motivated crusades is still being debated by historians. Realistically it seems most likely that the fighting was driven by both factors, material gain and religious differences. Even the Church’s involvement was likely driven by greed as much as zealotry.

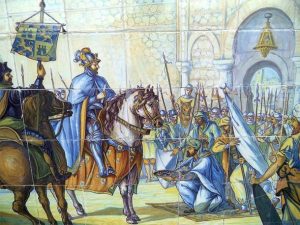

Alfonso VI and the “Reconquest” of Toledo during the Reconquista in 1085. (CarlosVdeHabsburgo / CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Rise of the Christian Military Orders & the Part They Played in the Reconquista

So, much of the fighting during the Reconquista can be divided into those fighting for personal gain and those fighting for “God.” The military campaigns that were said to be religiously inspired are known as the Crusades. These had the Church’s backing which came with several benefits, like mass recruitment via preaching and the use of church taxes to fund armies.

Spanish kings like Alfonso I of Aragon spent vast sums of money to tempt military orders that were fighting in the Middle East to send troops to Iberia. Alfonso, who had no heir, offered most of his kingdom to both the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar if they would send knights to aid him in the Reconquista.

It took decades of haggling, but it worked. In 1143 AD, after Alfonso had died, the Templars committed some of their knights, and the Hospitallers followed in 1148. Around the same time military orders unique to the peninsula began to form.

In 1158 AD the order of Calatrava, famed for the black armor its knights donned, joined the fighting. A few years later in 1170 the Order of Santiago reared its head, the Order of Montjoy followed in Aragon in 1173, then Alcantra in 1176, and Portugal’s Order of Evora in 1178.

The Knights Hospitaller and Templars might have been in the big leagues when it came to Crusading, but these smaller local orders had one advantage in that they didn’t have to send a huge portion of whatever they looted back to headquarters in the Middle East. As such, these Orders became immensely profitable and quickly grew in size.

As the fighting heated up, the rulers of the Spanish kingdoms no longer had to worry about sourcing fighters. As word spread of the unimaginable riches on offer in southern Spain, adventurous spirits from other parts of Europe, especially northern France and Sicily, began offering helping hands. The Christian armies were growing.

Assistance from the Second Crusade & the Taking Lisbon

Over the years, the papacy became increasingly involved in the fighting taking place in Iberia. It backed crusades to the Iberian Peninsula from 1113 to 1114, 1117 to 1118 and 1123 but things really kicked off during the period known as the Second Crusade (1147 to 1149).

People normally associate the major Crusades as having taken place in the Middle East, and it is true that the Second Crusade was mainly concerned with recapturing Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia (parts of modern Iraq, Syria, and Turkey). However, this Crusade also had secondary objectives in Iberia and the Baltic.

In the beginning of the Second Crusade the Second Crusaders were ostensibly made up of two groups, those set to sail to the Middle East from Europe, and those who had to march there over land. The problem was traveling by sea was much faster and the Pope didn’t exactly feel like paying half his forces to twiddle their thumbs while they waited for the other half to catch up. Much better to put them to work on the Iberian Peninsula instead.

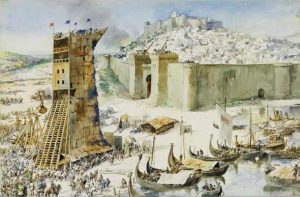

In 1147 AD a fleet of 160 to 200 ships full of Crusaders set sail from Genoa (a powerful city-state in medieval Italy) for Lisbon where their mission was to assist King Alfonso Henriques of Portugal in taking back the city from the Muslims.

It was a case of classic siege warfare. The siege began on 28 June 1147 AD with the Crusaders using huge siege towers and deadly catapults to pummel the defenders into submission. At its height, hundreds of boulders an hour were being hurled at the city walls. The city fell just four months later.

After this major success, many of the Crusaders left the peninsula for the Middle East, but some remained. Those who hung back to keep the fight going helped the Spanish kingdoms carry out several more major victories. On 17 October King Alfonso VII of Leon and Castille, backed by the Genoese (to whom he offered a third of the city) finally took Almeria in southern Spain.

In the following years Tortosa, a city in Eastern Spain, was reconquered by Christian forces led by the Count of Barcelona (who was once again backed by the Genoese, charging their customary one-third of the city).

Painting by Roque Gameiro depicting the Siege of Lisbon in 1147. (Public domain)

Ups and Downs During the Reconquista

These successes don’t mean the Reconquista was close to coming to an end, not by a long way. The next 60+ years saw plenty more fighting across the Iberian Peninsula with both the Spanish Kingdoms and the Muslim forces enjoying wins and suffering defeats.

One of the worst defeats for the Christians came at the Battle of Alarcos in 1195 AD. This was partly down to the fact that, even after all these years, the Christians still weren’t really united. In particular, King Alfonso IX of Leon had really made a mess of things by allying himself with the Muslims. A decision that led to Pope Clementine III excommunicating him and blessing any Christian soldier who fought against the traitor Alfonso with remission of their sins.

To be fair to Alfonso his decision to make an alliance with the Muslims wasn’t even anything new. Other kingdoms had been doing likewise for centuries, happily putting trade ahead of religion over the centuries, going all the way back to the Kingdom of Asturias we started our tale with. He’d just chosen a particularly bad time to do so.

Still, the defeat in 1195 and Alfonso’s supposed betrayal caused the papacy to once again become more involved. As a result, in 1212 AD Pope Innocent III officially backed the idea of liberating the Iberian Peninsula once and for all. It was a major turning point in the Reconquista.

Christian Victory: The Reconquista of Muslim Territory

The Muslim dominoes began to fall in 1212 with a major Christian victory. Christian forces, led by the three Spanish kings of Castile, Aragon and Navarre, smashed the forces of the Almohad Caliphate’s Muslim army at Las Navas de Tolosa. The Christian kingdoms had finally united, putting their internal disputes and rivalries aside to form a formidable alliance that was backed by the might of the Catholic Church.

The defeat at Las Navas de Tolosa both severely weakened the Almohad Caliphate’s control over the Iberian Peninsula and provided the Christian kingdoms with the momentum they needed to continue their efforts to reclaim territory from Muslim rule. This momentum led to the capture of Cordoba in 1236, Valencia in 1238 and Seville after a particularly arduous siege in 1248.

Eventually, Granada, located in southern Spain and ruled over by the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, was the only part of the Peninsula left in Muslim hands. It managed to hold out until 1492, but only because it paid tribute in exchange for being allowed to exist.

The Crusades Beyond the Battlefield

Deciphering the Truth Behind the Moors in Spain

Eventually, Granada fell too. In 1491 the devoutly Catholic Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, known as the Catholic Monarchs, began their siege of Granada with the assistance of their general Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba (also known as El Gran Capitán). On January 2, the Nasrid ruler Boabdil surrendered the city, effectively ending Islamic rule in Spain, uniting the Iberian Peninsula under Christian control and officially marking the end of the Reconquista.

With the end of the Reconquista, the Christian rulers looked away from their old Muslim enemies and instead started eyeing each other up. Very few Muslims had converted to Christianity and for the most part, the Christians left them alone, allowing them to remain on the peninsula and practice their religion in relative peace (at least for a while).

Many of the Christian States in Spain feared that the kingdom of Castile had become too powerful towards the end of the Reconquista. They worried that Castile would start gobbling up the other, smaller Spanish states, now the Muslims were defeated. Over the years these suspicions would lead to yet more bloodshed.

The Surrender of Granada, by Francisco Pradilla y Ortiz, depicts the moment which officially marked the end of the Reconquista. (Public domain)

La Reconquista – The Fight to “Reclaim” Spain

The long-term effects of the Reconquista were more troubling. It led to the idea amongst many Europeans that Christians were somehow fated to rule. This in turn led to both the Spanish Inquisition in 1478 and the issuance of the Alhambra Decree in 1492 which persecuted both Muslims and Jews and resulted in mass expulsions (and killings) of religious minorities across Spain.

Furthermore, the Reconquista became part of the Spanish and Portuguese national identities in the following centuries. When the Spanish and Portuguese landed in the New World, they took with them the lessons they had learned during the Reconquista; namely that Christianity could be spread by force and they could take what they liked from those they conquered in the name of God. It has taken many, many years for these old scars to heal, if they have at all.