Nero the Emperor: Creator or Antichrist?

Emperor Nero is one of the most notorious Roman emperors. But the man behind the myth seems to be far more complex.

Nero walks on Rome’s cinders, Karl Theodor von Piloty, c. 1861, Hungarian National Gallery

Emperor Nero holds a special place in history’s hall of infamy. After all, this is a man who killed his stepbrother and competitor for the throne as well as both of his wives. Moreover, Nero tried to murder his mother, and after several failed attempts, his assassins succeeded in reaching her.

The emperor was also known to be a ruthless persecutor of the early Christians (including Saints Peter and Paul). Lastly, an infamous scene (almost a meme) depicts the emperor “fiddling while Rome burned.” All these accusations, if true, indeed make Nero one of the worst Roman emperors. And yet, the reality is far more complex than the myth.

Most of what we know about Emperor Nero comes from the works of three historians: Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio. These works, written decades after Nero’s violent demise, were created with a clear anti-Neronian agenda by the people who belonged to the senatorial class. The new dynasty used those sources to build its legitimacy, tarnishing the name of the previous rulers, including Nero.

Nero, perhaps, was not a model emperor. Nor was he a particularly good one. He ascended the throne at a young age and remained in the shadow of his mother for too long. His policies and behavior were considered un-Roman by the elites, who detested the young ruler. Yet, Nero was popular among the populace. His unusual antics, and his obsession with theater and games made Nero one of the rare Roman rulers who genuinely tried to understand his subjects. Understanding Nero himself is not easy, but it is possible to unmask the man behind the myth.

Nero: The Unwilling Emperor

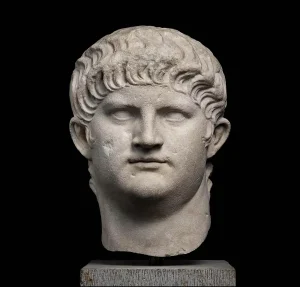

Marble statue of young Nero, 50-54 CE, Louvre Museum, Paris

When Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was born in 37 CE, little did he know that one day he would rule over the world’s greatest empire. Lucius was the son of Agrippina the Younger and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, who were both relatives of the first Roman Emperor Octavian (Augustus). However, the boy’s path to the throne was not guaranteed. When he was only two years old, Agrippina was exiled for her alleged participation in a plot against her brother, the reigning emperor Caligula. And a year later, the boy’s father died.

However, Caligula’s assassination in 41 CE turned the wheel of fortune once again, bringing Agrippina back from exile. In 49 CE, she married Emperor Claudius. The following year, the emperor adopted Lucius, giving him a new name — Nero.

Nero was only 13 years old. One can only assume what would have happened had his mother been different. Perhaps, Nero would have been remembered as a great artist or a successful athlete. Nero’s mother, however, was Agrippina — one of the most ambitious women in all Roman history. It is unclear if she was involved in the plot against Caligula. What can be said with certainty is that Agrippina played a crucial role in securing a place at the top for her son and herself. To approach Claudius, Agrippina had to get rid of her competitor, the emperor’s wife, Messalina. She then arranged her son’s marriage to Claudius’ youngest daughter, Octavia, further solidifying Nero’s claim to the throne.

Chalcedony cameo portrait bust of Agrippina the Younger, 37-39 CE, The British Museum

In 54 CE, Claudius died, either by natural causes or by poison. According to Suetonius, Agrippina played a role in Claudius’ demise, and she tried to prevent the emperor from designating Messalina’s son Britannicus as his heir. Suetonius’ report could be just a rumor (after all, Suetonius loved to gossip). Following Claudius’ death, however, the army and the Senate unanimously declared Nero the next emperor. The boy was not yet 17. Agrippina fulfilled her dream, becoming not only the most powerful woman in the Roman empire but a ruler in all but name.

All the Emperor’s Women

Silver coin with the joint portraits of Nero and Agrippina the Younger (obverse), the laurel wreath with an inscription (reverse), 54 CE, The British Museum

Agrippina exerted a significant influence over all Roman affairs, especially in the beginning of Nero’s rule. The extent of her power is visible in the coins minted in the first year of her son’s reign. One of the earliest coins features Agrippina on the obverse — the place traditionally reserved for the emperor. Other coins show a joint portrait of mother and son. Agrippina’s power, however, soon started to wane, as Nero tried to get rid of his mother’s overbearing influence. First, he removed Agrippina’s allies from all top positions. Nero’s involvement in the elimination of his stepbrother Britannicus could also be interpreted as an attempt to remove Agrippina’s potential ally. When Agrippina tried to befriend Nero’s wife Octavia, the emperor exiled his mother from the palace.

Nero’s marriage with Octavia was primarily a political affair instigated by Agrippina. Thus, the young emperor’s relationship with an ex-slave girl Claudia Acte further exacerbated the conflict between Nero and his mother. No longer his partner and ally, Agrippina became a burden and an obstacle. It is possible that Agrippina, unsatisfied with her position, got involved in a plot against her son. The sources on Agrippina’s death differ and contradict each other, but they all concur that Nero’s problematic mother survived several assassination attempts. The most famous one involved a self-sinking pleasure barge from which Agrippina miraculously escaped, able to swim ashore. Eventually, Nero’s assassins accomplished their task. Agrippina was killed, or, possibly, was forced to commit suicide.

The Shipwreck of Agrippina, Gustave Wertheimer, 19th century, private collection

Agrippina’s demise could have been the result of her opposition to Nero’s affair with Poppaea Sabina, another important woman in the emperor’s life. Poppaea also caused the banishment and then murder (or suicide) of Nero’s first wife Octavia. Unlike Octavia, who was allegedly barren, Poppaea gave Nero a child, thus ensuring the continuation of the imperial dynasty. Yet, happiness within the imperial family did not last long.

Nero’s daughter died only a few months after her birth. Another tragedy followed suit. According to the sources, overtaken by rage, Nero kicked the pregnant Poppaea in the belly, causing her death. The story perfectly matches the mad emperor’s established image. The sources, however, pursued a clear agenda and appeared decades after Nero’s death, thus the authors could not have possibly have known the details of the emperor’s private life. Further, the image of a pregnant woman kicked to death by an enraged husband appears in many pieces of ancient literature as a leitmotif, illustrating the (self) destructive tendencies of “mad” tyrants.

Marble bust, possibly of Poppaea Sabina, Italy, mid-1st century CE, Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome

Reality is less scandalous. Poppaea probably died from complications related to her pregnancy. Had she carried a son (or even a girl), it would have been illogical for the emperor to risk the death of a much-wanted heir even in a fit of rage. Death due to fatal complications of miscarriage or stillbirth were a common occurrence in the pre-modern era. Following Poppaea’s passing, Nero went into deep mourning. Poppaea not only received a state funeral, but was embalmed and deified. One could hardly have expected such a level of devotion from a murderous husband.

Hated by the Elites and Beloved by the People

Head of Nero, from a larger than life statue, after 64 CE, Glyptothek, Munich, via ancientrome.ru

Despite the anti-Neronian agenda, all sources agree that the first years of Nero’s reign were auspicious. Upon his ascension to the throne, Nero banished Claudius’ secret trials and issued pardons. If we are to believe Suetonius, Nero, when asked to sign a death warrant, exclaimed that he wished he had never learned how to write. During this first period of his reign, two competent and powerful men offered guidance to the young emperor, Nero’s tutor and advisor, Seneca, and the praetorian prefect Burrus.

It was on Seneca’s advice that Emperor Nero organized the Nile expedition, which led the Roman explorers deep into sub-equatorial Africa. Nero also presided over two military victories. His generals crushed the Iceni revolt in the recently established province of Britain, while the Roman legions achieved a rare success over Parthia, bringing the Armenian kingdom into the Roman orbit. In 66 CE, the new Armenian king visited Rome to receive his crown from Nero and offer his allegiance.

Although he was beloved by the people, the elites detested Nero. One of the primary reasons behind their animosity was Nero’s deep love for Greece and the East. As a boy, Nero was educated by renowned Hellenistic scholars and pursued art and poetry. If we are to believe the poet Martial, Nero was not an amateur. Few surviving examples demonstrate that the emperor took poetry seriously. Perhaps too seriously, since Nero is the only Roman emperor who personally participated in various plays and contests. Nero enjoyed watching theatrical performances and also playing in them. Such behavior caused another scandal, since in Roman society, actors were at the bottom of the social ladder.

Coin showing bust of Nero on the left, Nero laureate playing a lyre on the right, 62 CE, The British Museum

To make matters worse, Emperor Nero enjoyed another favorite Roman pastime — chariot racing. On several occasions, he personally drove a quadriga (a four-horse chariot). He even won races! Nero basked in his subject’s adulation. Towards the end of his reign, the emperor decided to travel to Greece and ordered the Greeks to squeeze all the major local festivals into one year. The Olympic Games were also shifted so that Nero could participate. Nero, thus, partook in over a thousand activities, “winning” all of them (including even those he did not attend). As a reward, he “liberated” Greece in 67 CE, exempting it from taxes (Vespasian annulled it a year later). Nero was no ordinary man.

For all his friendliness, Emperor Nero was, first and foremost, an autocrat. Nero’s wish was his people’s command. They had no choice but to obey. While the populace gladly accepted such a relationship, the elites were less enthusiastic about their philhellene emperor. Greece was the center of culture in the ancient world, and many senators sent their offspring to the East to get an education. But a blind obsession with all things Greek was perceived as a flaw, a mark of effeminacy and perversity. It did not help that Nero, in the absence of grand military victories and conquests, decided to burden the rich with property taxes to finance his ambitious building projects. The Senate naturally refused. Bit by bit, Nero’s hold over the empire began to weaken.

The Great Fire of Rome

The Fire of Rome, Robert Hubert, 1771, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre

One of the first associations awoken in a person’s mind upon hearing the name Nero is that of a plump figure clad in a toga, wearing a laurel wreath, standing on a colonnaded terrace, playing the lyre, while around him a great fire rages, devouring Rome and its helpless citizens. This image, immortalized by Hollywood, remains etched in our minds. It is the epitome of a careless, mad tyrant, indifferent to the great tragedy unfolding in front of his eyes.

The Great Fire of Rome is not a legend. On July 18th 64 CE, in the tenth year of Emperor Nero’s reign, a fire broke out in the Circus Maximus. Despite its grandiose appearance, Rome was a densely built city filled with easily flammable and badly constructed buildings. Yet, the extent of this particular catastrophe was unprecedented. The fire blazed for nine days. When it was finally extinguished, 10 of the 14 city districts were devastated, while three were completely destroyed.

Nero’s Torches, Henryk Siemiradzki, 1876, The National Museum, Krakow

Contrary to popular stories, Nero is hardly to blame for the disaster. By the time the fire started, he was not even in the city. Nero was resting in the villa at Anzio, 50 km from Rome. As soon as the emperor was notified of the fire, he immediately hurried back to the capital, where he personally led the rescue efforts. Nero even assisted the victims.

Tacitus, the only historian who was alive at the time of the Great Fire (although he was only 8), wrote that the emperor opened the Campus Martius and its lavish gardens to the homeless, constructed temporary lodgings, and brought food in at a subsidized price. The emperor also offered cash incentives to ensure the rapid recovery of the city, and passed and enforced new regulations to prevent recurring disasters.

But the emperor was not wholly blameless. Nero had to find a scapegoat to prevent an outbreak of violence among the populace or a full-scale revolt. He found his culprits in the local Christians — adherents of an eastern sect that already presented a nuisance. It is hard to determine how much of Tacitus’s account is accurate and how much of it is an invention. Nonetheless, the stories about terrible acts of violence committed against the Christians caused understandable resentment among them. Early Christian writers would continue to propagate this story, further embellishing it with horrific details as the sect’s power grew, making Emperor Nero a model Antichrist.

Nero, the Builder

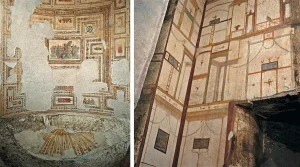

Domus Aurea, Ceiling decoration of the Hall of Achilles; with detail of the fresco from the Room of the Little Birds, ca. 64-68 CE, Rome, via Parco de Archeologico del Colosseo

Nero did not start the fire. But he undoubtedly profited from it. After the disaster, the emperor embarked on an ambitious rebuilding program. According to Tacitus, Nero tackled it with such fervor that many Romans soon started to question if he had ordered the fire in the first place. A century after Emperor Nero’s death, Cassius Dio saw this joy as crucial evidence of Nero’s guilt.

Nero’s building project was perceived as the ultimate illustration of the emperor’s megalomania. Indeed, the Domus Aurea (the Golden House) was a symbol of opulence. Covering Rome’s Palatine, Caelian, and Esquiline Hills, it was the world’s largest palatial complex. Some rooms were covered in gold and decorated with mother-of-pearl, precious stones, ivory ceilings, and special devices that diffused perfumes. The lavish complex contained numerous pools and fountains, elaborate gardens, and a large artificial lake. The highlight was the circular rotating dining room, a masterpiece of ancient engineering.

Despite the harsh criticism, Emperor Nero followed the pattern established by his predecessors. As exemplified in Tiberius’ villa in the coastal town of Sperlonga, Caligula’s lavish residence at the Horti Lamiani (atop Rome’s Esquiline Hill), and Claudius’s nymphaeum at Baiae (on the Gulf of Naples), each ruler wanted to outdo his predecessor. The emperors were allowed (and expected) to flaunt their wealth and status, but Nero took it too far. Or did he? The recent archaeological excavations suggest that the massive Domus Aurea was not intended to be a private residence but a public building. Nero’s huge new palace was to be a home for the people and their protector and artist — the emperor.

Visual reconstruction of the Domus Aurea, built after the Fire of Rome in 64 CE, by Josep R. Casals via Behance.net

Several public buildings constructed in Rome during Nero’s reign further confirm this hypothesis. Nero built magnificent public baths and a grand covered market. Particularly interesting is the Gymnasium Neronis. Before Nero, the gymnasia were a luxury to be enjoyed only by the rich. Nero shattered this division. From Nero onwards, those facilities became places for all citizens. The emperor also erected a wooden amphitheater to satisfy the need for public entertainment.

Emperor Nero: Villain or Victim?

Death of Nero, by Vasily. S. Smirnov, 1888, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

In 65 CE, the so-called Pisonian conspiracy failed to kill the emperor. Nero’s response was swift and harsh. The conspirators were sentenced to death or exiled. Among those killed was Nero’s old advisor, the philosopher Seneca. But the dissatisfaction of the elites with the despotic philhellene emperor could not be bottled up. In 68 CE, the governor of Gaul rebelled against Emperor Nero, declaring his support of Galba, the governor of Spain. The Gallic troops were defeated, but the emperor’s enemies gained the favor of a major part of the army.

When legions in Egypt halted vital grain fleets, Nero lost the support of Rome’s people. Abandoned by his subjects and declared an enemy of the state by the Senate, Nero fled the capital, ending his life with suicide. Suetonius tells us that the last words of the hapless emperor were: “What an artist dies in me!” What followed was the established Roman protocol of damnatio memoriae. Due to dwindling popular support, a private funeral took place, and Nero’s ashes were placed in the family tomb by his old flame Acte.

In the absence of a legitimate heir (Nero had no offspring), the Empire was plunged into chaos, known as the year of four emperors. Ultimately, Vespasian emerged victorious, establishing the new Flavian dynasty. To legitimize his claim, the new emperor erased both Nero and his work from the memory of the Romans. The Domus Aurea (which was probably still under construction) was abandoned and buried. In its immediate vicinity, the new emperor built the magnificent Colosseum, which is still standing. Only a small part of Nero’s palace survived, its magnificent frescoes well preserved. Both the Flavian and the Nerva-Antonine dynasties continued to vilify Nero, as did the Christians, whose troubles coincided with the narrative of a mad emperor.

The statue of emperor Nero by Claudio Valenti, erected in 2010 on the the waterfront of Anzio, Nero’s birthplace, via Wikimedia Commons

Centuries after his death, historians and artists adopted this image of a monster emperor. Hollywood, too, joined in, willingly playing the “madman” card, with great Peter Ustinov portraying the unhinged emperor Nero in the cult-classic “Quo Vadis.” Only recently, the tables have turned, with historians and archaeologists beginning to reconsider the man behind the myth.

Nero was a controversial emperor — a man who reluctantly took the throne following the grand plan of his mother. He then tried to get rid of her overbearing influence, ultimately succeeding to gain his independence through bloodshed. He was also the artist-emperor, beloved by the people and hated by the elites. Nero ruled peacefully and embarked on several grand projects. He also confronted one of the worst calamities that had ever hit Rome. Through all this, Nero succeeded. But it was not enough.

Nero’s conflict with the Senate echoed that of his uncle Caligula. In both cases, the emperors tried to impose their will and prove their supreme authority. In both cases, they were killed well before their time. Their names were tarnished, and they were branded as monsters for generations to come. The only difference is that while Caligula’s demise led to a peaceful transition of power, Nero’s death resulted in chaos. The bloody civil war brought forward a new dynasty, which damned not only Nero, but most of the Julio-Claudians, turning history into propaganda. Thus, the emperor who wanted to be an artist became an Antichrist.