It’s true that there is more variation in ancient Egyptian Kohl recipes than previously thought.

Researchers analyzed the contents of 11 kohl containers from the Petrie Museum collection in London and have revealed that the recipe for Kohl was more diverse than previously thought.

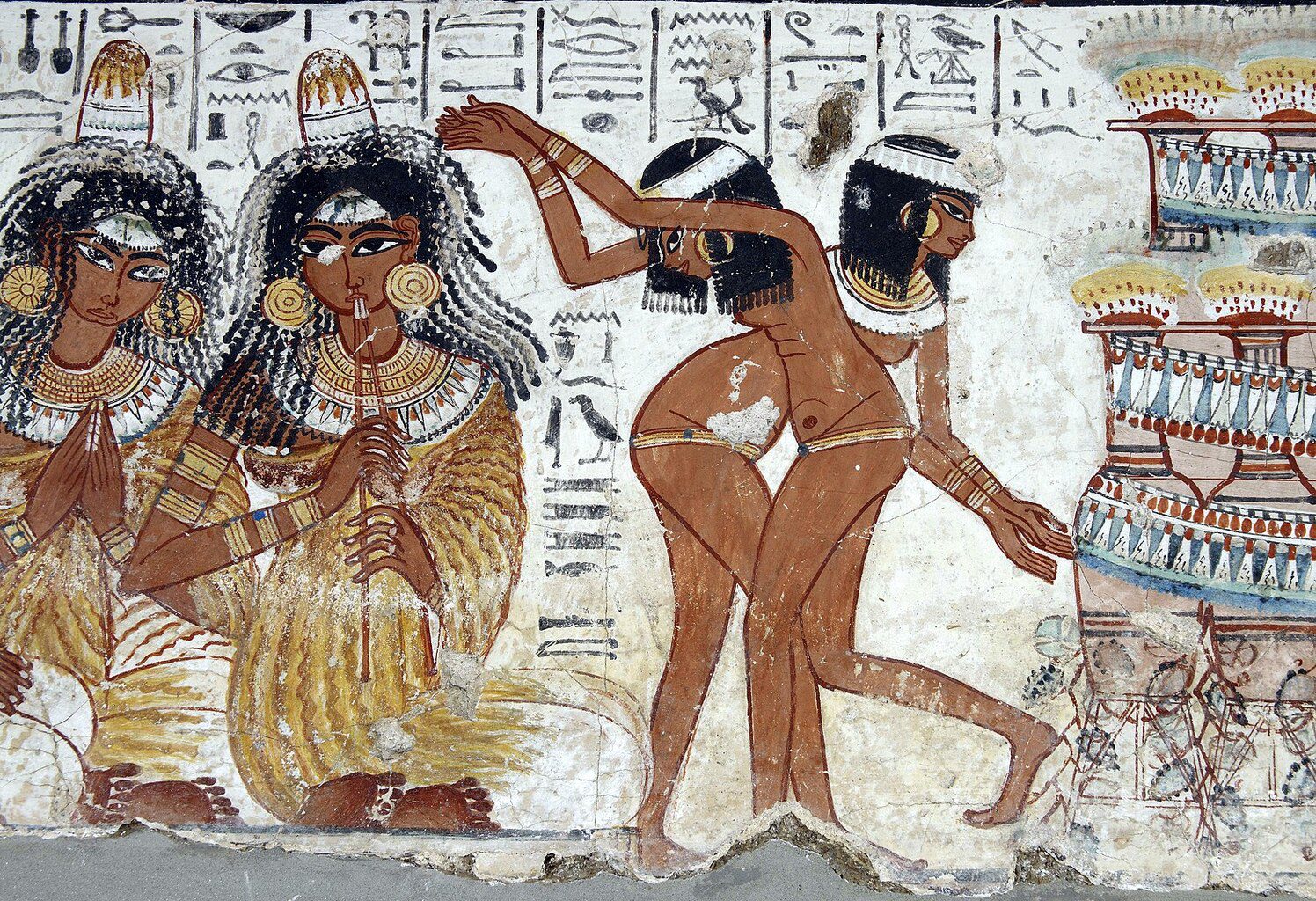

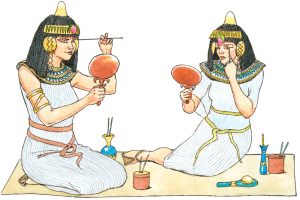

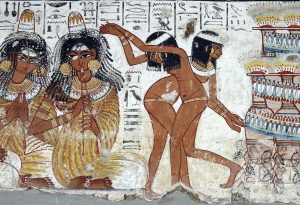

Kohl is a dark-eye cosmetic, popular in Ancient Egypt and many other cultures throughout the ages. The term ‘kohl’ is of Arabic origin and has been used to describe various types of drugs and cosmetics used on the eyes.

Kohl was used not only in ancient Egypt, but also by the Romans, Chinese, Japanese, Phoenicians, Indians, and Muslims. Kohl has been used since at least 5000 BC and continues to be used today.

Makeup was used in ancient Egypt not only for aesthetic reasons, but also for hygienic, therapeutic, and religious purposes. The traditional black or sometimes green kohl was part of sacred rituals and was also used for medicinal purposes.

Archaeological records show that green eye paint was more popular than black in pre-dynastic times, but around the beginning of the (proto) dynastic period, black became more common and largely replaced green.

The contents of kohl and various ways to prepare it differ based on tradition and country. Researchers analyzed the contents of 11 kohl containers covering a broad range of locations and periods from Ancient Egypt.

Map and pictures of the 11 kohl containers from the Petrie Museum.

Samples were screened using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) followed by Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS), Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD), and Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectroscopy (GC/MS). This allowed the team to characterize inorganic and organic constituent materials and formulate formulations for making kohl.

The resulting data indicated that Kohl’s was a heterogeneous mixture, which was divided into three main groups according to the results of the FTIR analysis: (1) inorganic predominant, (2) organic and inorganic mixed, and (3) unknown.

From an inorganic perspective, chemical analyses in the last few decades have identified a predominance of galena and other lead-based compounds in black kohls. The new study identified eight minerals previously not found in ancient kohl: biotite, paralaurionite, lizardite, talc, hematite, natroxalate, whewellite, and glushinskite, in addition to silicon-based, manganese-based, and carbon-based lead specimens.

The study also represents the first systematic study of organic components in kohls. It yielded six specimens that likely consist predominantly of organic materials such as plant oils and animal-derived fat. Taxonomically distinctive ingredients identified included Pinaceae resin and beeswax. All these findings point towards more varied recipes than initially thought and significantly shift our understanding of Ancient Egyptian kohls.