In medieval London, Black women were primarily affected by the Black Death.

When the Black Death or bubonic plague epidemic ravaged London between the autumn of 1348 and the spring of 1350, it may have wiped out as much as half the city’s population. While the victims of this frightening condition came from every social, economic and ethnic class, a new study carried out by researchers from England and the United States has revealed that Black women of African descent died at a higher rate from the plague than any other group.

This intriguing study, which was led by the Museum of London’s Human Osteology Curator Dr. Rebecca Redfern, involved a detailed analysis of 145 plague victims whose remains were excavated from three London cemeteries: the East Smithfield emergency plague cemetery, plus the burial grounds at St. Mary Graces and St. Mary Spital churches. By examining the bones and teeth of these unfortunate individuals it was possible to identify their racial heritage, and it was discovered that the number of African Londoners in these cemeteries was disproportionate to the percentages of people of African descent living in the city at that time. Black women were especially overrepresented, revealing an elevated risk for plague death that was unmatched by any other group.

A bubo on the upper thigh of a person infected with the Black Death. (CDC / Public Domain)

How Bioarchaeology Can Reveal Hidden Truths of Ancient Societies

According to Dr. Redfern and her associates, who included her long-time collaborator Dr. Joseph Hefner, an anthropologist from the Michigan State University, and Dr. Sharon DeWitte, a bioarchaeologist from the University of Colorado, their study is one of the first one to track the impact of racial disparities on vulnerability to the Black Death, the horrifying epidemic that was responsible for the death of between 30 and 50 percent of the population of Europe between 1347 and 1351.

Based on their findings, the researchers conclude that high death rates among people of color in that time and place demonstrate the “devastating effects” of “premodern structural racism” in the medieval world.

“Not only does this research add to our knowledge about the biosocial factors that affected risks of mortality during medieval plague epidemics, it also shows that there is a deep history of social marginalization shaping health and vulnerability to disease in human populations,” Professor DeWitte told the BBC.

In his comments about the findings, Dr. Hafner highlighted the value of the research approach his team adopted.

“This research takes the deep dive into previous thinking about population diversity in medieval England based on primary sources,” he said. “Combining bioarchaeological method and theory with forensic anthropological methods permits a more nuanced analysis of this very important data.”

What he is referring to here is the difficulty of learning about the experiences of marginalized or discriminated against groups living in ancient or long-defunct societies.

“We have no primary written sources from people of color and those of black African descent during the Great Pestilence of the 14th Century, so archaeological research is essential to understanding more about their lives and experiences,” Dr. Redfern explained. “As with the recent Covid-19 pandemic, social and economic environment played a significant role in people’s health and this is most likely why we find more people of color and those of black African descent in plague burials.”

A Plague of Discrimination Triggers a Plague of Death

Studying the lives of a marginalized and small population of people who lived in one city nearly seven centuries ago presents real challenges. Nevertheless, enough data has been recovered and analyzed to give researchers some idea of what life was like for people of African descent living in medieval London.

One scholar in particular, Professor Geraldine Heng from the University of Texas in Austin, has studied the experiences of African peoples who resided in London during the 15th century and earlier. Unsurprisingly, her work showed that Londoners of African descent experienced many forms of social, economic and political discrimination, which foreshadowed the city’s future involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

Some might question the use of a fashionable modern term like “structural racism” to categorize racial disparities in societies that are long gone and were quite different from our own. But few would dispute that life must have been extraordinarily hard for small communities of African people living in western Europe during the Middle Ages.

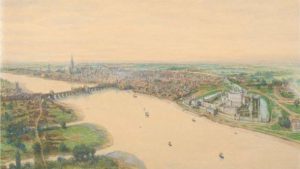

Painting of the Thames, and the Tower of London during the Middle Ages. (Museum of London)

Jobs for these individuals would have been extremely difficult to find, and chronic poverty and a lack of opportunity would have defined the existence of most. This would have inevitably predisposed people of African descent to experience poor outcomes when exposed to a contagious and deadly disease, since the bubonic plague was especially lethal for those who were malnourished, lived in crowded and unclean environments and experienced daily psychological and physiological distress.

Given the reasonable assumption that poor living conditions and a climate of discrimination contributed to the vulnerability of Black women to the plague, there is one anomaly that seems to contradict this theory. One obvious sign of economic disparity and a lower social status would be a lack of respect in the way the bodies of Black plague victims were disposed of, but this was not evident in the studies of the graves from the three cemeteries. The remains of these unfortunate souls were laid down carefully and respectfully, showing that they were given proper and dignified burials.

A severe shortage of documentation makes it difficult to draw any definitive and specific conclusions about what daily life was like for African Londoners in the 14th century. But what can now be said for sure is that the bubonic plague had a powerfully lethal impact on the city’s medieval Black community, with Black women being the most affected of all.