How the Usurper Emperor Magnus Maximus Was Made Into a Legend in Wales

Magnus Maximus is best known to history as a usurper of the Western Roman Empire. However, he also features prominently in Welsh legend.

There were many usurpers in the Roman Empire, some more successful than others. One of the most successful usurpers was a man named Magnus Maximus. He lived close to the fall of the Western Roman Empire, at a time when it started to experience serious troubles. Despite his defeat, Maximus left an indelible mark on Britain. How did this happen? And how does later Welsh legend depict him?

Who Was Magnus Maximus?

In the year 383, Magnus Maximus, who was serving in Britain, was proclaimed emperor by his troops. At the time, the Emperor of the West was Gratian, the son of Valentinian I, the Emperor of the East was Theodosius the Great.

Maximus launched an invasion into Gaul and quickly achieved considerable success. Emperor Gratian went out to defeat Maximus in battle. However, little more than a minor skirmish occurred, and then most of Gratian’s army switched sides. Maximus ultimately pursued Gratian and killed him. After about four years of reigning as emperor — during which he was even recognized by Emperor Theodosius of the East — war broke out again and Maximus was defeated.

Magnus Maximus in Britain

Depiction of Romans fighting barbarians from Varusschlacht, by Otto Albert Koch, 1909, via Wikimedia Commons

What do we really know about Magnus Maximus and his service in Britain? The earliest connection between Maximus and Britain as far as the available records are concerned takes us back to the year 368. In the year prior to this, 367, the so-called Great Conspiracy occurred, in which the Picts, the Scots, and the Attacotti almost completely overran Britain. At least one, but possibly two, prominent Roman leaders of Britain were killed in these attacks. In the year 368, Theodosius the Elder (the father of Emperor Theodosius the Great) was sent to deal with this uprising. Evidence from Zosimus and other early historians indicates that Maximus served under Theodosius during this event.

It does not appear that Maximus remained in Britain for very long after this event. He seems to have been used in other parts of the empire in the decade that followed, although exactly where is disputed. In any case, he eventually returned to Britain.

The Gallic Chronicle of 452, edited by Theodor Mommsen, 1892, via the Internet Archive

Exactly when Magnus Maximus returned is unknown. In any case, most modern sources assert that he was assigned to Britain in about 380. The Gallic Chronicle of 425 records that he was made a “tyrannus,” or unauthorized ruler, by his soldiers in that year. This contradicts all other literary evidence, which states that he was proclaimed emperor by his troops in 383. Perhaps the Gallic Chronicle’s statement comes from a confused memory of the fact that Maximus received a prominent position in Britain in 380, conflating it with his later usurpation.

Exactly what position Maximus held in Britain is debated. Many scholars believe he served as the dux Britanniarum, the chief commander of Roman troops in the north of Britain. This does seem like the most likely scenario. In 381, he won a victory against the Picts and the Scots, who usually raided from the north of Britain. And then, two years later, in 383, he was proclaimed emperor by his troops.

Remembered in Britain

Statue of Gildas, Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys, France, via Britannica

From the mere fact that Magnus Maximus was proclaimed emperor by his troops, we can see that he was evidently popular in Britain. It is no surprise, then, that he came to be remembered by the people there. He is one of the very few people mentioned by name in Gildas’ De Excidio, although this reference is an unfavorable one. Gildas was extremely pro-Roman, believing that the absence of the Romans was the reason the Britons were in such a difficult situation in his time. He focuses on the supposed fact that Maximus withdrew all of the Roman troops from Britain, which left the island extremely vulnerable.

Despite this, the vast majority of medieval Welsh texts which mention Maximus are positive. Exactly why there is this stark difference between Gildas and the other texts is likely because of their differing views on the Romans. Unlike Gildas, most later Welsh texts are not explicitly pro-Roman. Thus, deep in the era of powerful Welsh kingdoms, it may be that Maximus’ role in reducing the power of the Romans on the island was not viewed negatively, and perhaps was even viewed positively.

How Magnus Maximus Reorganized Britain

Ruins of Corbridge Roman town, via English Heritage

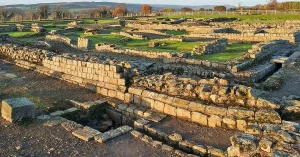

While Gildas’ claim that Maximus withdrew all the troops from Britain to invade Gaul is incorrect, it does come from genuine facts. We know that many Roman troops remained in Britain even after Maximus but the archaeological evidence indicates that some places did become abandoned in his time. For example, no Roman coins have been found at the fort at Malton, Yorkshire, from after Maximus’ reign. Archaeology also shows the abandonment of a number of inland forts in Wales.

However, Maximus also reorganized and even strengthened some areas. While leaving much of inland Wales undefended, he appears to have strengthened the sea defenses of that region instead. There is also evidence of a renovation at the fort of Corbridge in the north of England at this time. In fact, there is evidence that he even strengthened the region north of Hadrian’s Wall. However, contrary to what is sometimes claimed, this is not in conflict with the tradition that Maximus left much of Britain undefended. After all, his invasion of Gaul at the beginning of his usurpation is not the only time he is recorded as withdrawing troops from Britain. Near the end of his reign, in 387, Maximus is recorded as raising “a large army of Britons,” as well as other nations, when he attacked Italy.

Magnus Maximus as an Ancestor of Kings

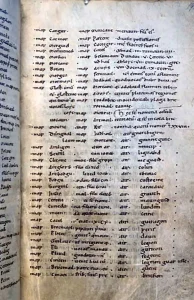

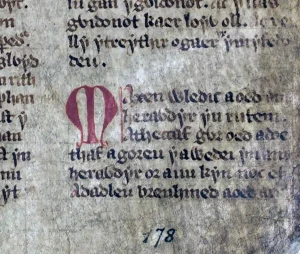

One of the dynasties allegedly descended from Maximus in the Harleian MS 3859, folio 195r, 12th century, via the British Library

Going by the major reorganization of Wales in the time of Maximus, it is no surprise that we find him portrayed as a type of founder in medieval Welsh texts. In a tenth-century genealogical record known as the Harleian genealogies, he appears as the ancestor of certain dynasties. One of these is the dynasty of Ynys Manaw — that is, the Isle of Man. Some scholars believe that this dynasty originally ruled over Galloway before later being expelled to the Isle of Man. Interestingly, Galloway is one of the regions which appears to have been strengthened by Maximus.

It is not impossible that Magnus Maximus really did have a son whom he set up as a type of ruler there as part of his reorganization of the region. Admittedly, though, only one son of his is mentioned in the contemporary Roman sources, and he was made the Augustus of Gaul.

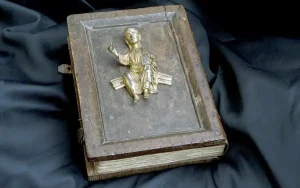

Book of Llandaff, 12th century, Llandaff, Wales, via the National Library of Wales

Even if Maximus did not genuinely start a dynasty in the north of Britain, it may well be that his notable strengthening of the region led to him being remembered as a founder there. From the Harleian genealogies, we also find that he was remembered as the founder of the dynasty of Dyfed, in southwest Wales. In fact, we can compare this record with certain others, such as Jesus College MS 20 and the Book of Llandaff. When we do, we see that Maximus was believed to have founded the dynasty of southeast Wales as well.

It is interesting to note the correspondence between this and the areas Maximus is known from archaeology to have reorganized and strengthened. The archaeology shows that he strengthened the coast of Wales, and here we see that he was remembered as the founder of the dynasties on the south coast. Again, while Maximus may or may not have actually fathered children who became rulers in this area, he clearly left a mark on that region.

Magnus Maximus’ Legendary Wife

Opening lines of The Dream of Macsen Wledig, via the National Library of Wales

One of the most prominent legends about Maximus involves him and his marriage to a British princess named Helen (spelled “Elen” in the Welsh records). The main source for this legend is a text known as The Dream of Macsen Wledig, part of a collection of tales called the Mabinogion. In this legend, Magnus Maximus, already emperor of Rome, dreams of a beautiful woman. He eventually finds her at Caernarvon, Wales, where she is Elen, the daughter of a king named Eudaf Hen. He marries her, and then he leaves Britain for the continent to fight against another emperor. Elen’s brother, Cynan, accompanies Maximus and helps him conquer Gaul and Italy.

It is clear that this legend derives from the historical career of Magnus Maximus, although in a highly distorted form. But the truth behind the legend of Maximus marrying Princess Elen is far from clear. One prominent scholar of this period, Peter Bartrum, wrote that “there is no reason to doubt this tradition.”

An illustration from The Mabinogion, by Charlotte Guest, 1877, via Wikimedia Commons

Notably, Maximus’ one recorded son is usually described as an “infant” by modern reference works. Since Maximus appointed his infant son as nominal Augustus in 383, this means that he must have been born while Maximus was in Britain. Therefore, the evidence shows that Maximus did have a wife who bore him a child while in Britain. But whether this was a local princess, we cannot say.

Of course, the very idea of there having been a king and a princess in Britain in this period might raise some eyebrows. Famously, the Romans did not allow independent kings within their realm, and they did not even have client kings in Britain after the first century CE. However, there is evidence of a more relaxed approach by the latter part of the fourth century. In the year 371, Emperor Valentinian I took Fraomar, the king of a Germanic tribe, and settled him in Britain with the rank of a tribune over his Germanic followers. For all intents and purposes, he was still the king of his people, yet ruling them within the empire. There may well have been de facto barbarian kings ruling in Britain, and Maximus may well have married into one of these dynasties to gain local support.

Magnus Maximus in Welsh Legend

Coin of Magnus Maximus, 4th century CE, via Baldwin’s

We can see that Magnus Maximus left a strong mark on Britain. He was clearly a popular leader and was effective in battle. From Britain, he conquered a considerable portion of the Western Roman Empire. Yet it was likely his activities in Britain itself that led to him being remembered so well by the Britons. He was remembered as a founder of several dynasties, particularly in the north of Britain and on the south coast of Wales. These traditions may well be related to the fact that they are locations Maximus reorganized and strengthened.

Magnus Maximus’ principal role in Welsh legend concerns his marriage to Elen and his subsequent alliance with her dynasty. While it is impossible to confirm, it seems that Maximus did have a wife of child-bearing age while he was stationed in Britain. We know that other usurpers were keen to have the support of local populations. We also know that it was not unheard of to have de facto kings in Britain at this late date. Therefore, it is not impossible that these legends have a basis in fact, as accepted by researcher Peter Bartrum.