Egyptian Treasures: A Special Exhibition at the Central Museum Eternal existence and mums

The mummy, along with the pyramids, is a keyword that symbolizes ancient Egyptian civilization and is a trace that clearly shows the thoughts of people at the time about the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians put a lot of effort into preserving the body, believing that the soul of the person who killed it stayed in the body, and with the geographical characteristics of Egypt being a desert region, many mummies remain to this day. In addition, the coffins and burials where the bodies were placed still contain the people’s wishes for the afterlife and how they lived.

Eternal life and mummy

The most necessary thing for eternal life was the body of a dead person. It was believed that eternal life in the afterlife was only possible if the body of the dead person was preserved, and mummifying the body was the beginning of the funeral process. The ancient Greek historian Herodotos mentioned in his History that mummification methods differed depending on cost, and that it cost a lot of money to make a perfect mummy. Additionally, it is said that it took about 70 days for the body to become a completely dehydrated mummy. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

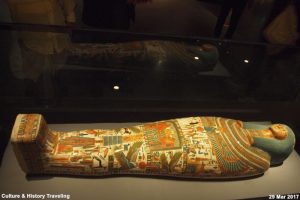

Coffin of Thothirdes, Saqqara, 791-418 BC (estimated 26th Dynasty), painted on wood, linen.

It shows a typical Egyptian mummy form consisting of a wooden coffin and a mummy.

The coffin lid, with various pictures and letters drawn on wood, expresses the wishes that the deceased wishes to achieve in the afterlife.

Picture drawn on the bottom of the coffin lid

A mummy with a body wrapped in linen cloth.

Egyptians believed that if the body of the dead was preserved in the form of a mummy, the soul would remain there.

In ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, mummy was written as ‘—’. This word also has meanings such as ‘nobility’ or ‘majesty.’ Mummification is also associated with eternal life, and the mummified body becomes a place for the soul to reside. ‘Totirdes’, the main character of this mummy, is presumed to have lived in the 26th Dynasty based on the shape of the coffin. The coffin depicts the wishes that Totirdes wishes to fulfill in the afterlife, and in the middle of the coffin lid, he is depicted standing before the gods after successfully passing the judgment of weighing his heart. And below, the goddesses Isis and Nephdis are mourning the mummified Totirdes, and Totirdes’ ‘Ba’ in the shape of a bird hovers above them. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Inner Cartonnage of Gautseshenu, Thebes (Luxor), 700-650 BC (25th-26th Dynasty), linen, gypsum, pigments

There are numerous paintings depicting Egyptian ideas about the afterlife.

The main character of this coffin, ‘Gaut Seshenu’, means ‘bouquet of lotus flowers’, and the Egyptian word ‘seshen (lotus flower)’ later became the origin of the name ‘Susan’. The coffin depicts several gods, including Osiris, the king of the afterlife, the jackal-headed Anubis, who guides the dead to the afterlife, and the four sons of Horus, the protagonist of the Canopus complex. Also appearing are the winged beetle Khepri, the god of the sky, Horus with spread wings and the head of a falcon, and Thoth, the ibis god of knowledge. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Coffin (Outer Sarcophagos of Paseba-Ichai-en-ipet), Thebes (Luxor), c. 1070-945 BC (21st Dynasty), whitewashed and painted on wood.

This is a coffin that housed an ancient Egyptian mummy decorated with colorful paintings.

The part of the face that reproduces the face of a dead person.

Picture drawn below. Typical Egyptian gods, including the goddess Isis, are depicted.

Entering the 21st Dynasty, the paintings that decorated the tomb walls were moved to the coffins and painted. The coffin of the main character of this coffin, ‘Pasevaikayenifet,’ depicts various gods and the killers who worship them. And the dead man is depicted as Osiris, describing the many gods he will meet in the afterlife. The wooden pipe is partially damaged, and this part shows how the craftsmen fastened the joints. Craftsmen first created the shape of the wooden coffin, applied plaster on it, and then painted it to make the surface smooth. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Coffin, Thebes (Luxor), c. 1339-1307 BC (18th Dynasty), painted on wood.

Drawing on the floor

The main character of this pavilion is ‘Teti, servant of the great place.’ Craftsmen who belonged to the middle class at the time would have paid a high price, roughly equivalent to a year’s salary, to purchase such a luxurious coffin. The chest of the human-shaped coffin is decorated with a round decoration with falcon heads at both ends, and below it is a bald eagle with wings spread wide. And a jackal, whose entire body is painted in black, is depicted sitting like a guardian deity guarding a tomb. (Guide, National Museum of Korea Special Exhibition, 2017)

Mummy Baord, Saqqara, c. 1295-1185 BC (19th Dynasty), whitewashed and painted on wood.

It shows the shape of a coffin without much decoration or painting.

The wooden mummy cover depicts the dead person wearing everyday clothes. What this protagonist is holding in his left hand is ‘ankh,’ which symbolizes life. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Sarcophagus Lid for Pa-di-inpu, Hardai (Cinopolis), c. 305–30 BC (Ptolemaic period), limestone.

This huge sarcophagus cover was made for ‘Padiinpu’, the royal secretary and priest. Even among the Egyptian upper class, only a select few were able to afford carefully crafted sarcophagi. The less wealthy members of the upper class used coffins made of inferior wood or clay. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Mummy Shroud of Neferhotep, Thebes (Luxor), Teir el-Medina, 100-225 AD, Roman period, painted on linen cloth.

In later generations, similar content was depicted in pictures on shrouds made from the cloth used to cover coffin lids.

The main character of the portrait depicted on this shroud made during the Roman era is ‘Neferhotep.’ This portrait shroud was made in place of a wooden lid. Discovered by French archaeologist Bernard Bruyere in 1948, some parts of it had already been damaged, but it was restored in the 1970s. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Mummy Shroud, Saqqara, 305-30 BC, Ptolemaic period, painted on linen.

During the Plemaic and Roman periods, the custom of wrapping corpses in richly decorated shrouds was popular. This shroud, of which only a portion remains, shows the man who appears to be the main character of the shroud and his faithful protector, Nephthys, standing on either side of the lower body of Osiris in the center. The man raises one hand in a sign of respect and holds a funeral wreath in the other. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Block Statue of Nesthoth, Thebes (Luxor), Karnak Temple, 305-30 BC, Plemaic period, diorite.

The name of the main character of this statue is ‘Nestot’, which means ‘one belonging to Thoth’. And on the front, a baboon symbolizing Thoth is engraved. This statue was placed by Nestot in the Temple of Karnak to worship his recipient, Thoth. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Block Statue of Padimahes, Leontopolis, 680-650 BC (25th to 26th Dynasties), granodiorite.

The protagonist of this sculpture is ‘Padhima Hes’, who is crouching down with his arms crossed and his face raised, looking in front of him. This statue was probably placed on the floor of the temple to represent Padimahes watching all the ceremonies and processions taking place before his eyes. The reason why human statues were placed in temples was because of the belief that one’s soul would come out of the tomb and enter the statue enshrined in the temple, so that it could share in the offerings offered to the gods. (Guide, Central Museum Special Exhibition, 2017)

Statue of a Family Group, Saqqara, c. 2371 – 2298 BC (5th – 6th Dynasties), limestone

Only a few people above the upper class were able to create their own family portraits. In this statue, the father is depicted larger than other family members, suggesting that it was a patriarchal society. Her wife is sitting, holding on to her husband’s calf, and her child is standing to her father’s right, putting her finger to her mouth. (Guide, Central Museum Special