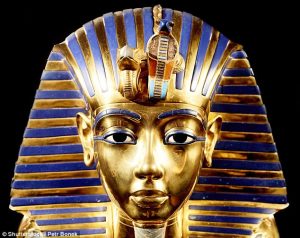

After almost a century, stunning Levantine gold artifacts discovered in Tutankhamun’s 3,340-year-old tomb are finally made public.

A number of gold pieces of artwork found in King Tutankhamen’s tomb made in Syria have been revealed for the first time in almost a century.

Almost 100 decorative fittings for bow cases, quivers and bridles were transported hundreds of miles to be placed in the Pharaoh’s 3,340 year old tomb.

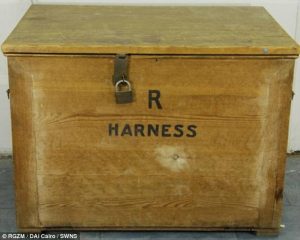

Their story can finally be told after they lay in a wooden box for more than 90 years after being discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922.

The box had laid undisturbed in a Cairo museum for decades before researchers spent four years restoring its deteriorated contents.

Among the finds are images of fighting animals and goats at the tree of life that are foreign to Egyptian art and must have come from the Levant, or modern day Syria.

Some of the gold artefacts (pictured) found in King Tutankhamen’s tomb were actually made in Syria rather than Egypt. Almost 100 decorative fittings for bow cases, quivers and bridles were transported hundreds of miles to be placed in the Pharaoh’s 3,340 year old tomb

Lead researcher Professor Peter Pfalzner, of the University of Tubingen in Germany, said: ‘Presumably these motifs, which were once developed in Mesopotamia, made their way to the Mediterranean region and Egypt via Syria.

‘This again shows the great role that ancient Syria played in the dissemination of culture during the Bronze Age.’

The embossed gold relics were found by his team in the very same crate in which they were placed in 1922 after the famed find by Carter.

At the time, the relics were photographed and packed into the crate, where they were left to deteriorate for almost a century.

During four years of detailed work, conservators at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, reassembled the fragments to produce the almost complete embossed gold decorations.

They also made drawings of the items and carried out comprehensive research.

Professor Pfalzner and colleagues examined and categorised the artwork on the artefacts.

The team distinguished Egyptian motifs from those that could be ascribed to an ‘international’, Middle Eastern canon from the Levant.

Among them are images of fighting animals and goats (pictured) at the tree of life that are foreign to Egyptian art and must have come from the Levant – or modern day Syria

These would have been shipped around 400 miles (645 km) to modern day Cairo across desert and water.

The ancient Egyptians didn’t build roads to travel around their empire as they didn’t need them, thanks to the Nile.

Most major cities were located along the banks of the iconic river.

As a result, they used it for transportation from very early on, becoming experts at boat building and navigation.

The embossed gold relics were found by his team in the very same crate in which they were placed in 1922 after the famed find by British archaeologist Howard Carter

At first they were long, thin and made of papyrus plant, and were steered with oars and poles.

But eventually bigger cargo ships made of wood, acacia from Egypt and imported cedar from Lebanon were built, with sails jutting from the middle and a large rudder at the back.

The Egyptians sailed these ships up and down the Nile and into the Mediterranean Sea to trade with other countries.

Some were used to carry huge stones weighing as much as 500 tons from rock quarries to pyramid building sites.

The restored artefacts can now be seen at a special exhibition at the Egyptian Museum, which opened on Wednesday.

Professor Pfalzner said similar artefacts with images along a comparable theme were found in a tomb in the Syrian Royal city of Qatna.

There, his team discovered a pristine king’s grave in 2002. It dates back to the time of around 1340 BC, just a bit older than King Tut’s tomb dating back to 1323 BC.

The restored artefacts can now be seen at a special exhibition at the Egyptian Museum, which opened on Wednesday

Prof Pfalzner said: ‘This remarkable aspect provided the impetus for our project on the Egyptian finds.

‘Now, we need to solve the riddle of how the foreign motifs on the embossed gold applications came to be adopted in Egypt.’

He said chemical analyses has been illuminating.

As well as showing the incredible craftsmanship in ancient Egypt, the researchers believe that the bed also provides an insight into the aspirations of King Tut

‘The results showed the embossed gold applications with Egyptian motifs and the others with foreign motifs were made of gold of differing compositions.

‘That does not necessarily mean the pieces were imported. It may be various local workshops were responsible for producing objects in various styles – and that one used Near Eastern models.’

He added that, almost a century after they were discovered, the scientific analysis of these artefacts from one of Egypt’s most sensational archaeological finds has finally been completed.