A Roman Senator’s Day in Ancient Rome: A Gear of Rome

The Roman Senate played a significant role in the evolution of ancient Rome. A snapshot from the life of a Roman senator is an ideal way to understand this institution.

The Roman Senate was one of the most enduring institutions in the ancient world. It was established at the dawn of Rome, and it survived the fall of the Roman Monarchy, the fall of the Roman Republic, the division of the empire, and the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476. It achieved its ascent to power during the Republic and it was finally weakened at the beginning of the Middle Ages. In this article, we will explore a fascinating day in the life of a Roman senator from the time of the Roman Republic.

What Did Roman Senators Do?

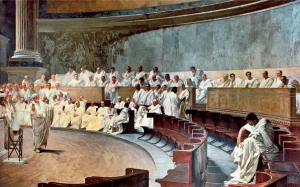

Cicero Denounces Catiline, by Cesare Maccari, 1889, via Wikimedia Commons

The Senate was composed of elderly men, which is why the word for senate means “old man” in Latin (senex). The primary function of the Roman Senate was to debate decrees and create laws, any of which could be approved or declined (in Latin veto) by the consuls or leaders of the Senate.

Furthermore, it decided Rome’s external policy, managed expenses, and supervised religious matters. In matters of war, the Senate decided the number of troops necessary for a campaign, controlled the generals, and offered them honors. The final decision of the Senate on a matter was known as a Senatus Consultum, and every magistrate had to accept it. Their decisions were similar to decrees and functioned similarly to laws.

How did patricians become senators? First, They were not elected but appointed. Throughout much of the Roman Republican period, an elected official, the censor, appointed new senators. Later during the Roman Empire, the emperor controlled who could become a senator. Secondly, Senators were required to be of high moral character. They had to be wealthy because they were not offered payment for their jobs and had to spend their wealth on running the Roman state. They were not allowed to have other jobs, such as being a banker or a merchant, nor could they commit any crimes.

Short History of the Roman Senate

The Curia Juthe lia, official meeting place of the Roman Senate, built by Julius Caesar, 44 BCE; later reconstructed by Diocletian, 305 CE, via the Colosseum

We can trace the history of the Roman senate to the earliest roots of Rome itself. Centuries before the founding of the Eternal City, the early Indo-European settlers of Italy were organized into tribal communities and found themselves in need of a common form of community. As a solution, the patriarchs (patres) from the leading clans (gentes) were selected for the confederated board of elders, the precursor of the Roman senate. According to Livy, Rome’s first king, Romulus, created the senate, which consisted of 100 men.

During the earliest period of the Roman Monarchy (753-509 BCE), the Senate was composed of 300 clan/gentes leaders. The early senate had both consilium and auctoritas. Consilium (from the verb consulere, to consult) meant that during the period of the Roman monarchy, the Senate was a consultative institution, offering counsel to the Roman king. Auctoritas comes from the term “authority”, and it refers to the right of the Senate to ratify any political decision.

After the fall of Roman kingship and the transition to the Roman Republic (c. 509–27 BCE), the Senate was politically weak, while the various executive magistrates were more influential. It is believed that the transition toward constitutional rule took place gradually. As a result, the Senate was able to regain its position only after several generations, by the middle Republic. During the late Republic, the Senate fell yet again into decline after the reforms of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus.

Cenotaph of the Gracchi by Jean Baptiste Claude Eugène Guillaume, 1853, via Web Gallery of Art

During the Roman Republic, the senate was composed of 300 magistrates and ex-magistrates. The members of the senate were recruited by two censors who would pick magistrates from the two classes of ancient Rome, the patricians and the plebs. The first chosen senator held the title of Princeps Senatus. Depending on their title, there were several categories of senators, such as viri censorii, consulares, praetorii, and tribunicii. For example, being a vir Praetorius meant that the senator with this title was previously a praetor. The previous attributes, consilium and auctoritas, remained unchanged during the Republic. In times of crisis, the senate could also name a dictator.

During the Principate (27 BCE-284 CE), the Senate declined further, losing almost all of its political power and prestige. The final blow came during the reign of Emperor Diocletian, whose reforms made the Senate politically irrelevant.

After the seat of government was transferred from Rome to Constantinople, the Senate became a municipal body. A second senate, created by Constantine the Great, further sealed the original one’s fate. Finally, after the fall of the Western Empire (in 476) came Ostrogothic rule (476-489) and a short period of byzantine control. The Senate finally disappeared some time after 603.

A New Day

Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, ca. 50–40 BCE, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Without a doubt, roman senators were held in high esteem within their community. They enjoyed several honors and prerogatives and were wealthy citizens. As a result, they lived in lavish households compared to the simple homes of poorer citizens.

The day began early for a senator and the members of his household. He would usually get up at dawn. His slaves were up even earlier, sweeping, dusting, and polishing. After waking up, it did not take long for him and his wife to dress up. The first garment he put on was a tunic, a type of short-sleeved shirt, and a toga, a large piece of woven cloth arranged in folds. His shoes, very similar to modern sandals. As a senator, he would wear over his toga a laticlave as an emblem of office. Laticlavia means “broad nail” or “broad stripe” in contrast to the “narrow stripe” (angusticlavia) worn on the tunics of lower social ranks.

Dressing was followed by a quick wash of the hands and face with cold water. On other occasions, a senator would take a bath in his private bath. His wife would follow the same routine. As a wealthy Roman wife, she would wear a full-length tunic or a stola and a large shawl. A slave-woman would assist her in doing her hair, putting on her make-up, and arranging her jewelry.

The breakfast (jentaculum) was eaten very early, and it consisted of simple foods: salted bread, milk, or wine, and perhaps dried fruit, eggs, and wheat pancakes with honey or cheese. However, it was not always eaten, or it was simplified to a glass of water and a piece of bread. Food was served by slaves or pre-cooked.

Working the Gears of the Eternal City

The Roman Senate, by Gökberk Kaya, via Art Station

The day was divided between business and leisure. Most of the work or business was conducted in the morning. Romans worked six hours every day, starting after dawn and ending at noon. A typical day of senatorial work consisted of discussions and finding solutions to all sorts of problems Rome faced.

A meeting of the senate was convoked by a magistrate who would decide on the matters to be discussed, moderated the discussion, and assisted the senators in making a decision. Their decision was known as a Senatus Consultum which in theory was not imperative due to the traditional formulation si eis videbitur — meaning if they see fit. Practically speaking, the decision was imperative due to the important position of the Senate.

Sejanus Condemned by the Senate, illustration by Antoine Jean Duclos, via the British Museum

The subjects discussed at these meetings reflected the diverse areas of competence of the Roman Senate: tax, public works, naming magistrates for the provinces, determining the number of troops and spending money for military campaigns or wars, managing foreign policy, and the granting of honors.

If Rome was threatened, then the Senators could appoint a dictator. This was an extraordinary magistrate who held full authority to resolve some specific problem to which he had been assigned. He was granted full powers over the state, subordinating all other magistrates for the specific purpose of resolving that issue, and that issue only, and then after resolving the crisis, those powers were returned to the state.

Julius Caesar, by Peter Paul Rubens, 1619, via the Leiden Collection

After work, a senator would either seek entertainment or go home. He might attend, with his friends, different kinds of games (wrestling, gladiatorial competitions, or races at the Circus Maximus), watch a play at the theater, or relax at a public bathhouse.

All of these places were enjoyed by both the rich and the poor. The Roman lunch (cibus meridianus or prandium) was a quick and light meal eaten around noon and would include salted bread with extra ingredients such as fruit, salad, eggs, meat or fish, vegetables, and cheese.

The Day Ends For Roman Senators

A Roman Feast, by Roberto Bompiani, 1821-1908, via the J. Paul Getty Museum

After work and leisure, dinner was served. The dinner (cena) represented the main meal of the day and would be accompanied by watered-down wine. A senator would enjoy an upper-class dinner that included meat (fish, goat, or beef), vegetables, eggs, and fruit. He would start with a course of light dishes to whet his appetite (egg, fish, cooked and raw vegetables). Then he came to the main course in which a variety of meat dishes with different sauces and vegetables would be served. Finally, the desserts were brought in, consisting of fruits, nuts, cheese, and sweet dishes. After eating, dinner ended with a final serving of wine, known as Comissatio.