A Comprehensive Knowledge of the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate saw significant evolution over the centuries of Rome’s existence, and in the end outlasted all its kings and emperors.

The Roman Forum by Hodgkin, 1800-1860, via The British Museum, London

Eager young politicians in modern nations today might be disappointed to learn that the word “senate” derives from the Latin “senex,” meaning “old man.” The original Roman Senate was quite literally a governmental body made up of the oldest, most venerated citizens. Over the centuries, the Roman Senate saw dramatic changes to its composition, influence, and powers. Yet ultimately it would outlast even the emperors of Rome, being a staple of Roman government from its first coalescence to its final dissolution.

Capitoline She-Wolf, famous Roman bronze sculpture depicting Romulus and Remus, 1021-1153 AD, via The Capitoline Museum, Rome

The very first origins of the Roman Senate are not well understood. 100 members comprised the first Senate, representing various families of the founding tribes and functioning as an advisory body to the king. Though others would join, the descendants of these original one hundred Senators became the Patrician class, the most distinguished and elite members of Roman society, and a powerful boost to their political careers. Those first one hundred may have been chosen and sent by their own families, or they may have been appointed by Romulus, Rome’s first king.

The Roman Senate And The Roman Monarchy

Tarquin the Elder Consulting Attus Navius by Sebastiano Ricci, 1690, via The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Although the Roman king may have created the Senate, ironically the most power vested in the Senate of Rome’s monarchy was that of determining the executive. Roman kings did not automatically pass their power onto their heirs. Instead, upon the death of a king, power reverted back to the Senate. A senior member would function as regent during the period known as the interregnum, and then suggest a candidate to be the next king. The Senate would then decide whether to nominally approve the suggestion. Next, the people voted whether to accept the individual and finally the Senate gave their ultimate approval.

The Death of Lucretia by Gavin Hamilton, 1763-67, via The Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

As the Sabine and Latin tribes joined with Rome, an additional one hundred Senators from each tribe joined the assembly. The tyrannical tendencies of the final king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, led to his deposition. During his years of reign, he executed numerous senators, and upon his exile, some of his supporters left with him. Lucius Junius Brutus and Publius Valerius Publicola, two of the first councils of the newly formed Republic, appointed high ranking plebeians and equities to fill the vacancy and brought the number back to around three hundred. This remained the occupancy for several centuries to follow.

The Republican Senate

The Secession of the People to the Mons Sacer by B. Barloccini, 1849, Private Collection, via PBS

Establishing the Republic grew the Roman Senate’s responsibilities. For the first few centuries, most of the actual legislative power still sat with the smaller assemblies and the magistrates. The Council of Plebeians further divided that power. In response to their feelings of under-representation, the common people of Rome staged a massive “walk-out” of Rome, forcing the Senate to grant them some political clout. The tribunes of the Plebs received the ability to veto Senatorial decisions and the assembly gained some real political influence.

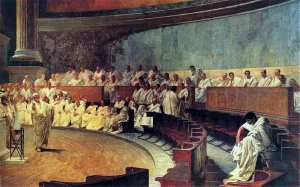

Cicero Denounces Catiline by Cesare Maccari, 1888, in the Maccari Hall of Palazzo Madama, Rome

Despite this, the power of the Senate continued to grow throughout the days of the Republic. The consuls, dual senior Senators appointed by that body as the highest authorities in Rome for a term of one year, commanded both the military and the civil administration of Rome. The Senate controlled money, day-to-day administration, and foreign policy. In the latter years of the Roman Republic, the Senate was a political powerhouse both in and out of Rome, frequently hearing appeals from foreign nations to intervene in their various conflicts.

The Decline Of The Roman Senate

The Curia of the Theatre of Pompey, 62 BC, a common Senate meeting place in the late Republic and the site of Julius Caesar’s assassination

Political stature was one of the defining goals of Roman men, and as such, a position as Senator and eventually consul was the ultimate goal. This also made Senatorial appointments a major reward. Since consuls appointed Senators, they held a unique position to grant that kind of reward to their supporters. Roman politicians also performed multiple governmental duties, serving as assembly members, governors of provinces, and military leaders. As corruption in the Roman Senate deepened, the numbers of senators grew and the standards to which they were held lessened. Senators did not receive a salary and therefore looked to extortion as provincial governors or military plunder to build their fortunes, a trend that continued into Imperial Rome.

The Death of Caesar by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1859-67, via The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Various individuals attempted to enact reforms to counteract the decay, including the Gracchi brothers and Sulla. In his capacity as dictator, Sulla raised the number of senators to 600. After the success of Julius Caesar’s civil war, he raised the number to almost 900 or 1000 while granting power to his supporters. The huge number of senators also effectively neutered the Senate’s prestige and power; perhaps that was Caesar’s intention. Yet by the time of Caesar’s civil wars, the Roman Senate was already corrupt and ineffective, and the establishment of a more dominant executive power was likely inevitable. Caesar’s nephew and successor, Augustus, understood that, but also firmly grasped the importance of the Senate and at least the appearance of the Republican government.

Augustan Reforms

Statue of Augustus, 1st century AD, via Musei Vaticani, Rome

Augustus trimmed the Roman Senate back down to 600 members by removing those he deemed unworthy. He also re-established expectations of morality and conduct, enforced by censors who could remove a senator from the assembly for inappropriate behavior. Under Augustus, the list of current senators was required to be made public for inspection by the people. To be eligible for membership in the Senate, one needed to own property with a value of at least one million sesterces. Senators also could not leave Italy without receiving the permission of the other senators, engage in banking, take on any public contract for work, or own a ship large enough to take part in foreign trade.

Although the true power of government rested with Augustus, he was careful to be an active and respectful participant. He made an effort to sit in on Senate meetings and took their counsel seriously. His successor, Tiberius, initially continued this stance, before eventually retiring from political life and attempting to lead remotely while enjoying a luxurious lifestyle at his ornate villa on the island of Capri. In the decades to follow, however, the Senate lost much of its actual power and became instead little more than a status symbol.

The Senate as Emperor-Maker

Death of Nero by Vasily Sergeyevich Smirnov, 1888, via The Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg

The one power that the Roman Senate retained, even as emperors took over the major functions of government, was the power with which it had begun: controlling the executive. Despite Rome’s continuing distaste for kings, it had ironically returned to a state that closely paralleled the early days of its monarchy. Though varying emperors treated the Senate with different degrees of respect and deference, they still nominally derived their powers from the approval of that Senate. In extreme cases, the Senate could, and did, declare an emperor an enemy of the state, thus condemning him and ensuring his removal from power. It was an act that they could not enforce if the emperor still held the support of the military, but allowed the assembly, particularly in times of turmoil and civil war, to direct the outcome of executive power.

Proclaiming Claudius Emperor by Sir Lawerence Alma-Tadema, 1867, via Sotheby’s

Yet even this power did not last forever. The military and the Praetorians, the emperor’s personal guards, and the only individuals allowed to carry weapons within the city limits of Rome, grew more involved in the acclamation of new emperors. The Praetorian Guard famously assassinated Emperor Caligula, then, upon finding his uncle Claudius hiding behind a curtain in the palace and immediately declared him emperor. Lacking the physical ability to enforce their decisions, the Senate had to capitulate to the decisions of those that were armed. Their actual political power steadily declined over the first few centuries of the new millennium.

The Roman Senate and The Division of The Empire

The Founding of Constantinople by Peter Paul Rubens, 1622-23, via The Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe

The split of the Roman Empire into two halves under the rule of the Tetrarchy continued this decline. In the early 4th century A.D., Emperor Constantine established a new capital at the ancient city of Byzantium, rebuilt and rededicated as Constantinople in his honor. Constantine established a new Senate in his new eastern capital, and the original Senate of Rome became a shadow of its former self, concerned only with local and municipal matters.

Yet Constantine’s rule was a high watermark for the latter Empire. He was the last man to jointly rule all of Rome. After his death, the divide between East and West increased. The eastern Roman Empire thrived, going on to be the powerful nation that modern historians have christened the Byzantine Empire. The Western Empire failed, with its final emperor, Romulus Augustus, deposed by Flavius Odoacer, who set himself up as king.

The Curia Julia, a meeting place of the Roman Senate, commissioned by Julius Caesar and completed by Augustus, 44-29 BC, Rome

The moment is considered by many to be the official fall of the Western Roman Empire. Yet the Senate continued to function under his rule and that of the Ostrogoths who eventually displaced him. The very final known act of the Roman Senate in the west occurred in 603 A.D. The Curia Julia, the traditional meeting place of the Senate built by Julius Caesar and completed by Augustus, was transformed into a church in 630 A.D.