A 4,500-year-old Spanish woman survived two radical head surgeries.

Researchers analyzing a woman’s skeleton unearthed from a Copper Age graveyard on the Iberian Peninsula discovered clear and unmistakable proof that this individual had undergone two surgeries to her head sometime before she’d died. But while these were serious and invasive surgical procedures, the woman survived these ancient medical treatments and lived for at least a few more months, or possibly even longer.

The Copper Age woman’s remains were initially recovered from a burial site known as Camino del Molino, which is located in Caravaca de la Cruz in southeastern Spain. The skeleton was accidentally unearthed by earth moving machines used for a construction project in 2007, and successfully excavated and removed from its original resting place one year later.

The Camino del Molino site turned out to be a huge ancient cemetery from which 1,348 bodies were ultimately recovered, and it was eventually determined that the burial site was in use between 2566 and 2239 BC, or between 4,262 and 4,589 years ago.

The Copper Age woman’s skeleton as seen at the burial site. (Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al)

Trephination: The Oldest Evidenced Surgery Still in Use Today?

Skulls Show Evidence Ancient Chinese Brain Surgeons Operated 3,000 Years Ago

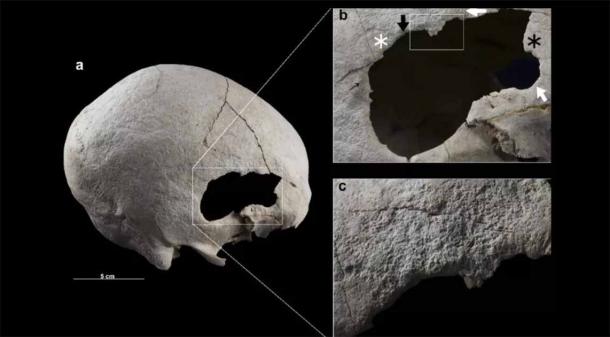

The skull of the woman, whose estimated age was between 35 and 45 years old when she died, featured two holes in her skull that ran deep enough that they would have exposed the outermost layer of cellular tissue that comprised her brain and spinal cord. The two oblong holes actually overlapped between her temple and the top of her ear, and measured 2.1 inches wide by 1.2 inches long (53 by 31 mm) in one case and 1.3 inches wide by 0.47 inches long (32 by 12 mm) in the other.

The type of surgical procedure that was performed on the woman’s skull is known as trepanation. The general idea of trepanation was to relieve pressure or swelling on the brain, which was believed to be linked to conditions that caused head pain or neurological malfunctioning. Trepanation was first used as a form of medical intervention sometime between 7,000 and 10,000 years ago, and even now it is still used to help treat a few specific conditions.

A Copper Age women underwent two separate surgical procedures that left two overlapping holes in her skull. (Sonia Díaz-Navarro et al)

Despite the obvious dangers of trepanation, especially in prehistoric times, it seems the Copper Age woman survived these radical procedures. This was not always assured, as past studies of prehistoric trepanations suggest a 40 percent mortality rate was common.

“The survival of Individual S21 from both trepanations is evident and there are no signs of ectocranial and endocranial infection or other complications,” the Spanish scientists wrote in an article about their study published in the International Journal of Paleopathology. “Although no pathological signs have been documented in the skeleton explaining reasons for the intervention, it is possible that the surgery was performed as a consequence of a trauma, especially taking into account the high frequency of cranial injury in the Camino del Molino collection.”

The openings in the skull featured sharp and well-defined edges, and there were no fractures radiating outward from those edges. This showed that the holes were made intentionally (and with great care) and could not have been the result of a head injury.

Based on the “oblique orientation of the hole walls,” the researchers concluded that the holes in the woman’s skull were made using a “scraping technique.”

“This involves rubbing a rough-surfaced lithic [stone] instrument against the cranial vault, gradually eroding it along all its edges to create the hole,” study lead author Sonia Díaz-Navarro, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Prehistory at the University of Valladolid in Spain, told Live Science. “To perform this surgery, the affected individual likely had to be strongly immobilized by other members of the community or previously treated with a psychoactive substance that would alleviate pain or render them unconscious.”

In the area around the holes, there were clear signs of healing in the bones. As a consequence, the researchers believe the woman must have lived for at least a few months following the second surgery, and it is even possible she survived for a period of years.

It is not unusual to discover skulls that have undergone trepanation in ancient graveyards, or in burials that are just a few centuries old for that matter. But none of the other skeletons found at Camino del Molino showed any indications of having undergone the procedure.

One interesting aspect of these surgeries is that they were performed over the brain’s temporal region, rather than on the top or front of the head (the usual locations).

The hazards of surgery in the temporal region included “inherent challenges associated with accessing this area through the scalp,” Diaz-Navarro said, noting that this part of the brain contains a plethora of exposed blood vessels and muscles that can be easily cut and bleed profusely. But she also pointed out that scraping is a safer form of trepanation than drilling, being less likely to cause collateral damage to the brain or post-surgical infections.

A Surgical Success Story for the Ages

The researchers have been unable to determine why the woman needed two head surgeries. If she suffered from injuries or pain that affected soft tissue this would be impossible for the modern analyst to detect, since only bones will remain after a body has been buried for 4,500 years.

“The high prevalence of traumatic injuries documented in the skeletons from Camino del Molino leads us not to rule out the possibility that the surgery may have been performed as a result of trauma,” Diaz-Navarro said. Even though evidence of head wounds is not currently observable, the trepanation holes may have obscured some pre-existing damage to the skull.

Whatever the truth about the woman’s cause of death, there is no doubt that she was treated by someone who knew what they were doing and could perform a delicate procedure successfully. Needless to say, this was quite an accomplishment for a “surgeon” operating with hand-made copper tools in the year 2500 BC.