The Ishtar Gate and the Babylonian Deities

The Ishtar Gate was the main entrance into the great city of Babylon, commissioned by King Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BC) as part of his plan to create one of the most splendid and powerful cities of the ancient world. The discovery of the ancient gate in 1902 by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey was met with awe, and its reconstruction in 1930 revealed its architectural splendor. But the discovery of the Gate of Ishtar revealed much more than the building accomplishments of the Babylonians; it shed light on the religious beliefs and customs of the once powerful Empire of Babylon.

The Role of Ishtar in Ancient Near Eastern Kingship Rituals

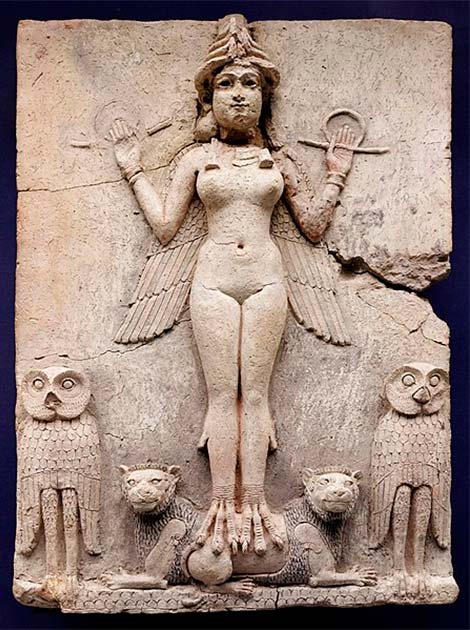

The Ishtar Gate is so named, because it was dedicated to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, the East Semitic Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian goddess of fertility, love, war, and sex. She is the counterpart to the Sumerian Inanna, and in the Babylonian pantheon, she was the divine personification of the planet Venus. Her cult was the most important one in ancient Babylon; it is believed to have included temple prostitution, although this is debatable. According to the noted Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer, kings in the ancient Near Eastern region of Sumer established their legitimacy by taking part in a ritual sexual act in the temple of the fertility goddess Ishtar every year on the tenth day of the New Year festival Akitu.

Old Babylonian period Queen of Night relief, often considered to represent an aspect of Ishtar (Gennadii Saus i Segura/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Depictions of Deities: Understanding the Iconography of Ishtar and Adad

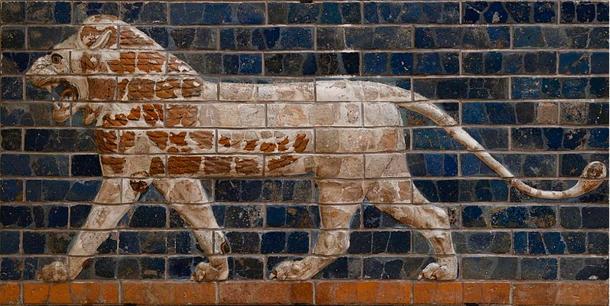

Leading from the grand entrance of the Ishtar Gate was the Processional Way, a pathway lined with sculptural reliefs of lions, aurochs (bulls), and dragons, in which Nebuchadnezzar II paid homage to the Babylonian deities through the animal representations. The lion is associated with Ishtar – as the goddess of war and the protector of her people, the winged Ishtar was depicted holding a bow and quiver of arrows and riding a chariot that was drawn by seven lions. She was sometimes shown standing on the back of a lion, or in the company of two lions.

Sculptural relief of a lion along the Processional Way. (Dosseman/CC BY-SA 4.0)

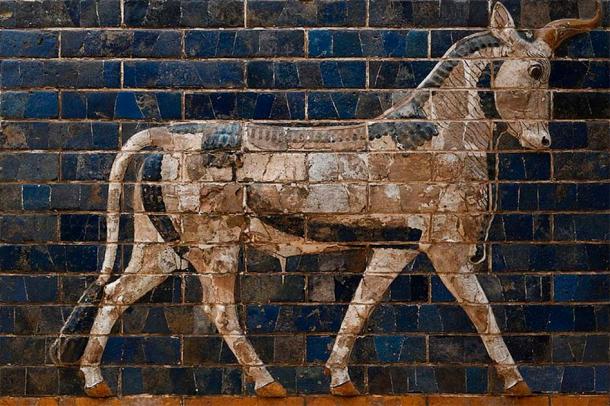

The auroch is an extinct type of large wild cattle that inhabited Europe, Asia and North Africa and is the ancestor of domestic cattle. The young bulls are associated with Adad, a weather god in the Babylonian pantheon. Adad had a twofold aspect, being both the giver and the destroyer of life. His rains caused the land to bear grain and other food for his friends, which his storms and hurricanes, evidences of his anger against his foes, brought darkness, want, and death. Adad was typically represented brandishing lightning bolts and standing on or beside a bull.

Sculptural relief of an auroch (bull) along the Processional Way. (Dosseman/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Dragon Symbolism: Unveiling the Representation of Marduk

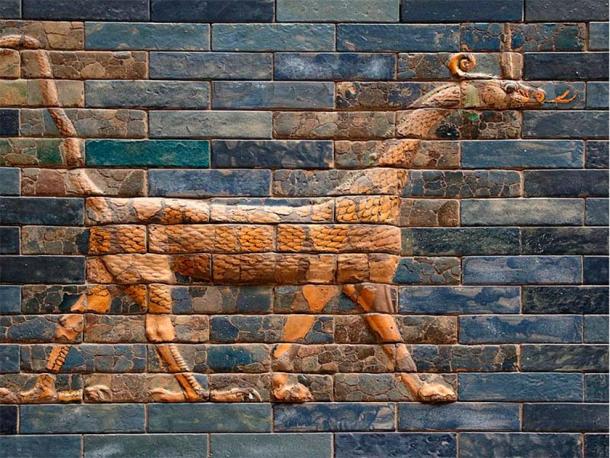

Finally, the dragon (sirrush) is a symbolic representation of Marduk, the chief god of Babylon. Marduk’s original character is obscure but he was later associated with water, vegetation, judgment, and magic. According to ancient mythology, Marduk defeated Tiamat, a chaos monster and primordial goddess of the ocean who mated with Abzû (the god of fresh water) to produce younger gods.

The presence of the snake-dragon has been a matter of much debate among researchers who pointed out that the mythical animal was out of place next to sculptures depicting known animals (lions and bulls) that were contemporary with the Babylonians. The creature, often referred to as sirrush or mušḫuššu (“splendor serpent”) can be described as having a slender body covered with scales, a long slender scaly tail, and a serpent’s head with a long forked tongue.

Robert Koldewey, who discovered the Ishtar Gate, seriously considered the notion that the sirrush was a portrayal of a real animal. He argued that its depiction in Babylonian art was consistent over many centuries, while those of mythological creatures changed, sometimes drastically, over the years. In 1918, he proposed that Iguanodon (a dinosaur with birdlike hind feet) was the closest match to the sirrush.

Snake-Dragon, Symbol of Marduk, the Patron God of Babylon. Panel from the Ishtar Gate. Detroit Institute of Arts. (Raffaele pagani/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Akitu: Babylon’s New Year’s Festival and Divine Procession

The sculptural reliefs of lions, aurochs, and dragons representing powerful deities sent a powerful message to all who entered the great gate that Babylon was protected and defended by the gods, and one would be wise not to challenge it.

Every spring, a great procession that included the king, members of his court, priests, and statues of the gods passed through the Ishtar Gate and along the Processional Way to the “Akitu” temple to celebrate the New Year’s festival.

“The dazzling procession of the gods and goddesses, dressed in their finest seasonal attire, atop their bejeweled chariots began at the Kasikilla, the main gate of the Esagila (a temple dedicated to Marduk), and proceeded north along Marduk’s processional street through the Ishtar Gate,” wrote Julye Bidmead, a professor at Chapman University, in her book “The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia”.

Anahita and Ishtar: Connections to the Planet Venus

3000-Year-Old Assyrian Reliefs Unearthed in ISIS Stomping Ground

The name ‘Akitu’ is from the Sumerian for “barley”, originally marking two festivals celebrating the beginning of each of the two half-years of the Sumerian calendar, marking the sowing of barley in autumn and the cutting of barley in spring. In Babylonian religion it came to be dedicated to Marduk’s victory over Tiamat.

The Akitu festival was continued throughout the Seleucid period (312 – 63 BC) and into the Roman Empire period. Roman Emperor Elagabalus (r. 218-222), who was of Syrian origin, even introduced the festival in Italy. A number of contemporary Near Eastern spring festivals still exist today. Iranians traditionally celebrate 21 st March as Noruz (“New Day”), while Kha b-Nissan is the name of the spring festival celebrated among the Assyrians on 1st April.