How Did the Romans Destruction Carthage in the Punic Wars?

The three Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage lasted intermittently, over nearly a century, from 264 to 146 BCE. In the end, Rome was victorious.

The Battle of Zama, anonymous, 1567-1578, via Art Institute of Chicago

The Punic Wars, also called the Carthaginian Wars (264–146 BCE), were a series of wars between the Roman Republic and Carthage for control over the Western Mediterranean. At the onset of the war, Rome was the underdog. It was a land-based power with virtually no navy, confronting the powerful fleet of Carthage. Yet, despite initial defeats, Rome persisted and built its own navy, taking control of Sicily and winning the First Punic War. The second of the conflicts brought Rome to the brink after brilliant Carthaginian general – Hannibal Barca – invaded Italy, the very heart of the Republic.

Rome persevered once again and, under the leadership of Scipio Africanus, turned back the tables, beating Hannibal on its home turf in Northern Africa, winning the war once again. Determined to end Carthage’s threat once and for all, the Third Punic War saw the complete destruction of the once proud maritime empire, including the town of Carthage. This complete erasure of Carthage from the map left Rome, master of the Mediterranean, paving the way for the establishment of the Empire.

Punic Wars: Rome vs Carthage

Carthage, by Jean Claude Golvin, via jeanclaudegolvin.com

On the eve of the Punic Wars, Carthage was the master of the Western Mediterranean. Founded around 750 BCE, as a colony of the Phoenician city of Tyre, Carthage formed a massive empire by the third century BCE. It controlled northern Africa, southern Spain, and the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. Yet, its power was not derived from the land but from its mighty fleet that protected naval trade routes all across the Mediterranean and beyond, as far north as Ireland. After all, the Phoenicians were expert merchants and sailors.

However, Carthage’s supremacy was soon to be challenged. After taking control of the Apennine peninsula in the Samnite Wars, Rome – another power founded in the mid-eighth century BCE – now looked south towards the island of Sicily. Interestingly, Rome and Carthage had been in friendly contact, trading with each other and even forming an alliance during the Pyrrhic War. The peace was not to last. As often, the sparks of the war started with a struggle between the minor states. Few could know that this seemingly unimportant conflict would lead to a collision course between two ancient superpowers and reshape the map of the Mediterranean and the world.

First Punic War (264 – 241 BCE): Rome Becomes a Naval Power

The Western Mediterranean at the beginning of the First Punic War, in 264 BCE

The first of the Punic Wars (named after the Roman name for “Phoenician” – Punicus) erupted in 264 BCE. After the group of Italian mercenaries, called Mamertines, revolted against the king of Syracuse and took Messana (modern Messina), they appealed to both Carthage and Rome for help. While the Roman Republic debated what to do, Carthage recognized the opportunity and garrisoned the town. Carthage was now in control of the Messina Strait, vital to grain shipping for Rome. In 263 BCE, 40 000 Roman soldiers landed on Sicily. The First Punic War had begun.

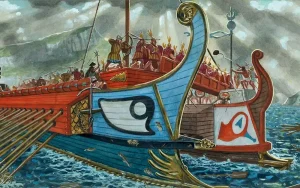

With Carthage located on the other side of the Mediterranean, the First Punic War was limited to the island of Sicily and the surrounding waters. Initially, Carthage, a maritime superpower, held the upper hand over Rome, which possessed little sailing experience and a meager fleet. Yet, the Romans were able innovators. According to the historian Polybius, who left us a detailed account of the war, the Romans used a shipwrecked enemy boat as a template, embarking on a large naval building program in 260 BCE. Soon, Rome had its first significant navy, consisting of 100 large quinqueremes and 20 smaller triremes.

The artistic representation of the Battle of Mylae (260 BCE), showing a corvus boarding bridge in action

Despite impressive Roman advancement, Carthage’s superior seamanship and numbers — over 300 ships — could not be easily outmatched. Nor could Roman sailors compare to much more experienced Carthaginian mariners. Romans, however, had an advantage in land combat, winning the battles on the island. To make use of the legionaries, Romans invented the corvus (“raven”). This was essentially a wooden boarding ramp with a long metal spike at the bottom. After the Roman warship rammed into an enemy’s hull, the corvus would be lowered, locking the two ships together. Naval combat would become a land battle.

The corvus brought a much-needed advantage for the Romans in the naval battles. In the Battle of Cape Ecnomus of 256 BCE, one of the largest naval engagements in history, 300 Roman ships defeated a 350-strong Carthaginian fleet, sinking 30 and capturing 64 hostile warships. Finally, in 241 BCE, at the Battle of Aegates, the Roman fleet dealt a decisive blow to the enemy. With its naval power crushed, Carthage was forced to sue for peace, bringing the First Punic War to a close.

Second Punic War (218 – 201 BCE): Hannibal’s Failed Gamble

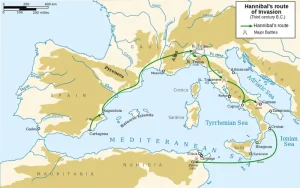

The route of Hannibal and his armies

The First Punic War ended as a triumph for Rome. Carthage lost most of its fleet, had to pay war reparations and leave Sicily, which became the first Roman province. But it was not the end. Under the leadership of Hamilcar Barca, one of the most prominent Carthaginian commanders, Carthage turned westwards to Spain, where Hamilcar established the colony of New Carthage (now Cartagena). After Hamilcar perished in a battle, command passed to his oldest son, Hannibal. As a young boy, Hannibal gave an oath to avenge Carthage’s defeat and bring ruin to Rome. In 218 BCE, an opportunity presented itself after the Romans allied themselves with the Saguntum, the town in the Carthaginian zone of influence. Hannibal promptly attacked and gained control of the city, sparking the Second Punic War.

Hannibal Crossing the Alps, by Heinrich Leutemann, 19th century, via Yale University Art Gallery

Hannibal was well aware that Carthage could not compete with the Roman navy. Instead, the brilliant general took a bold gamble, striking at the very heart of the enemy. In the late spring of 218 BCE, Hannibal and his crack troops, including 38 war elephants, crossed the Alps. It was a daring crossing, and Hannibal lost many men, and all of the elephants, to the hazardous conditions and the snowy mountain passes. Yet the gamble paid off. Bolstered by the local tribes, Hannibal’s army defeated not one but several Roman legions at Ticinus, Trebbia, and Trasimene. Each time Hannibal was outmatched. Each time the Carthaginian military genius outmaneuvered and crushed his enemies. But his major coup was yet to come.

Bust of Hannibal

After months of avoiding open battle and a scorched earth policy devised by Quintus Fabius Maximus (also known as a delayer or “cunctator”), the Roman Senate decided that the time was right to eliminate Hannibal once and for all. The two consuls — Terentius Varro and Aemilius Paulus — were given joint command of a massive army of around 80,000 men. The largest army Rome had ever assembled had one task — to stop Hannibal. Instead, Varro and Paulus led their army to Rome’s worst defeat. On August 2, 216 BCE, Hannibal annihilated the Roman army at Cannae. Eight legions were wiped out, and most of their commanders perished in the battle. Six centuries later, Ammianus Marcellinus would call emperor Valens’ defeat at Adrianople, the worst Roman military disaster after Cannae.

Yet, despite the clear and present danger of “Hannibal ante portas” (Hannibal at the gates), Rome refused to surrender. Instead of giving in, Rome, under the leadership of one of a few survivors of Cannae — young Publius Scipio — doubled down. Scipio decided to isolate Hannibal and his troops in Italy while using the remaining Roman troops to strike directly at the heart of Barcid power in Spain. Unable to move from Italy and denuded of reinforcements, following the destruction of the relief army at the Battle of Metaurus River, Hannibal could only look as the Romans drove Carthaginians out of Spain.

Battle of Zama, by Giulio Romano, last third of the 16th century, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

The decisive and last battle of the Second Punic War took place in 202 BCE at Zama. This time, it was Hannibal who suffered a complete defeat, while the winner became known as Scipio Africanus. Hannibal wanted to continue fighting, but Carthage decided to sue for peace. Hannibal spent the rest of his life in exile, in the Hellenistic East, with Romans in hot pursuit. Finally, in 183 BCE, Hannibal committed suicide by drinking poison, thus outmaneuvering his foe for one last time.

Third Punic War (149 – 146 BCE): One Empire Ends, Another Rises

Bust of an elderly man – so-called patrician Torlonia, believed to represent Senator Cato the Elder, 1st century CE, Fondazione Torlonia, Rome

Hannibal’s invasion of Italy traumatized the Roman Republic. Determined to prevent further challenge from Carthage, Rome forced its rival to renounce all of the Mediterranean possessions, disband the fleet, and pay huge war reparations. The Romans went even further, forbidding Carthage to wage any war without Rome’s approval. Carthage was now, in all aspects, a client state. Yet, the peace brought a new period of prosperity to the North African town, to such an extent that Carthage paid its war reparations in only ten years! This rapid recovery was looked upon with extreme suspicions by the Romans. Famously, the prominent Roman senator — Cato the Elder — completed each of his speeches in the Senate with the sentence: “Carthago delenda est” or “Carthage must be destroyed!”

Finally, in 150 BCE, the Carthaginian war with Numidian king Masinissa brought the Romans opportunity they had waited for so long. Despite Carthage defending itself, the Roman envoys made an ultimatum: Complete disbandment of the military and 300 hostages of the most prominent Carthaginian families to be sent to Rome. Even now, Carthage relented and fulfilled all of the requirements. Then in 149 BCE, Rome demanded the dismantlement of the city of Carthage and the resettlement of its population inland, away from the coast. It was a step too far.

Print of Hannibal of Carthage, John Chapman, 1805, via The British Museum, London

Carthage’s rejection of the harsh demands sparked the last war. The Third Punic War was nothing else than a “war of destruction.” From the outbreak of hostilities, Carthage was outnumbered and outgunned. However, the Romans underestimated the resilience of the Carthaginians, who knowing that this was a fight for very survival, prepared themselves for the long siege. During the following three years, the defenders repelled each Roman attack and burned the entire hostile fleet. Finally, in 146 BCE, the arrival of the new Roman commander, Scipio Aemilianus (later known as Scipio the Younger), the adoptive grandson of the famous “Africanus,” signaled the end for the ancient city.

By then, famine reigned in the doomed city. Yet, even in this poor condition, the inhabitants continued the heroic defense, fighting for every house, every street, every temple. It took a week of street fighting for the defenders to capitulate. Roman vengeance was horrendous. All of the 50. 000 surviving citizens were sold into slavery. Carthage was plundered and razed to the ground.

Archaeological Site of Carthage (Tunisia), photo by Jean-Jacques Gelbart, via UNESCO World Heritage Centre

However, despite attempts to wipe out the city from existence, including salting the soil (although there is no evidence for such an act), the town’s favorable location led to refounding of Carthage in 44 BCE. In the centuries that followed, Roman Carthage would once again become one of the most important cities of the ancient Mediterranean. As for the Roman Republic, the victory in the Punic Wars opened the gates for further conquests, and takeover of the whole of the Mediterranean, ending with the annexation of Ptolemaic Egypt in 30 BCE.

Ironically, the triumph over Carthage also put the Republic on the path to its ruin, as the long overseas campaigns led to the creation of a professional army loyal not to the Senate but to its commanders. After several bloody civil wars, one of those military leaders, Octavian, finally toppled the Republic, becoming the first Roman emperor — Augustus.