Top 10 Alexander the Great Battles

From Thebes to Gaugamela and from there to the Sogdian Rock, these are Alexander the Great’s top 10 battles.

Alexander the Great of Macedonia was a unique tactician and general, undefeated in the field. In addition to the extreme loyalty that his soldiers held for him, spurred on by his courageous leadership at the front of every battle, his ability to think of unexpected solutions to problems and defeat overwhelming odds time and time again made him a deadly enemy. His battle tactics would be studied by other ancient generals for centuries to follow. These top 10 of his greatest battles receive that distinction for a variety of reasons; some for careful strategy despite being outnumbered, some for innovative engineering and planning, and some for sheer courage and audacity.

1. The Battle of Thebes (335 BCE)

View of Thebes by Hugh William Williams, 1819, in the Benaki Museum, Athens

After the assassination of Alexander’s father, King Philip II, many of the conquered Greek nations to the south believed the transition of power to be a possible time to stage a bid to regain their independence. One of the most prominent of these was Thebes. Emboldened by reports of Alexander falling in battle with the Triballi tribe to the north, Thebes launched their rebellion with the verbal support of Athens. However, Alexander was far from dead, and he immediately took steps to quell the unrest, performing a quick march south with his army. The Macedonians moved so quickly that, at first, their Greek opponents wouldn’t believe it could be Alexander, still arguing that he must have died and it was a different Alexander commanding the soldiers now moving towards them.

However, the other Greek city-states abandoned Thebes, and Alexander laid siege to the city. One of Alexander’s commanders launched an early attack without orders, forcing Alexander’s hand and the start of a full-scale assault. The Macedonians successfully breached the walls, and a major slaughter took place within the city. Alexander also apparently lost 500 men, a high causality rate for him in later years. Thebes was razed and its remaining population sold into slavery, a judgment given by the League of Corinth as Thebes had violated sacred treaties with their rebellion.

2. Battle of Granicus (334 BCE)

Alexander the Great at the Battle of the Granicus against the Persians, by Cornelis Troost, 1737, in the Rijks Museum, Amsterdam

Granicus was Alexander‘s first encounter with Persian forces on the battlefield. It was a comparatively minor engagement, though an important first victory for the advancing Macedonians. The Persians did not yet understand the exceptional talent of their enemy and had moved a smaller force quickly to engage with Alexander as he first entered Asia Minor. Alexander arrived at the banks of the Granicus River late in the day to find the Persian forces camped on the other side. Most commanders would not have wanted to begin a battle so late in the day. Alexander took advantage of that fact to surprise the Persians with his assault, leaving them minimal time to bring up their infantry behind the cavalry that formed the forefront.

The left wing of the Macedonian army kicked off the attack, taking heavy casualties in the riverbed. However, they successfully drew the attention of the Persians and turned their line slightly in that direction. After holding back for the shift, Alexander led his Companion Cavalry in an attack on the right flank. The fighting was fierce as Alexander and the closest soldiers crested the riverbank, and Alexander was almost killed in the moments that followed. Still, when the remainder of the cavalry had made it across, the battle was essentially won. They crashed into the flank of the Persians and began a rout, handing the victory to Macedonia and firmly establishing Alexander’s move into Persian territory.

3. Battle of Issus (333 BCE)

The Battle of Issus Mosaic, showing Alexander the Great confronting Persian King Darius, ca. 100 BCE, via the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

Issus was the site of the first direct encounter between Alexander and Darius, both commanding their armies in a full-scale battle against one another. Alexander had been heading south from the town of Issus in an attempt the intercept the Persian King, unaware that Darius had already headed north, looking for the Macedonian forces. Learning, to his surprise, that Darius was already behind him, Alexander turned his army back, and confronted the Persians at the Pinarus River. Darius, who believed he was chasing a retreating Macedonian army, was caught for battle in an area that heavily disadvantaged his larger force.

The Battle of Issus by Jan I Brueghel, 1602, in the Louvre, Paris

Although the Persian army greatly outnumbered the Macedonians, the battlefield was bordered on one side by the Gulf of Issus and on the other by the rough terrain of the foothills of the Amanus Mountains, limiting the number of soldiers he could send into battle at one time and almost neutralizing his powerful cavalry forces. Alexander took full advantage of his well-chosen ground and his tactical knowledge. Fully aware that the numbers were on the Persians’ side, he employed the same strategy that he would later use at Gaugamela — get to King Darius. Killing, capturing, or forcing the Persian King to flee the field would present him with victory.

Heavy Losses

The Family of Darius Before Alexander by Paolo Veronese, 1565-1567, in the National Gallery, London

The Persians fought fiercely and caused many casualties on the flanks, but Alexander and his Companion Cavalry eventually succeeded at their plan to punch through the middle in a daring wedge attack and come up on the flank of Darius’ personal guard. Darius was forced to flee the battlefield or risk losing the entire war and all of Persia, and his retreating army suffered heavy losses as the Macedonians pursued them from the field. Even worse, Darius’ flight allowed the Macedonians to capture the Persian baggage train, which included Darius’ family, his mother, wife, and children.

4. Siege of Tyre (332 BCE)

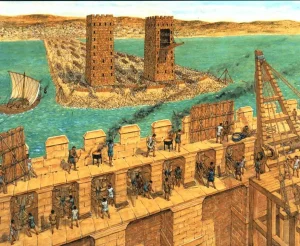

Artist’s impression of the Siege of Tyre, depicting Alexander’s massive siege towers and a causeway under construction, by Duncan B. Campbell, via amusingplanet.com

The great city of Tyre was a wealthy metropolis and was already over two millennia old by Alexander’s era. Located on the eastern shores of ancient Syria (modern-day Lebanon), it was a strategic harbor port with incredible defenses that had once held up against a thirteen-year siege by King Nebuchadnezzar II. By the time Alexander arrived outside the walls of Tyre, he had conquered much of the coast of Asia Minor. The king of Tyre attempted to open diplomatic discussions with Alexander, but after a religious misunderstanding that resulted in the Macedonian King perceiving a slight against his honor and subsequent hostilities against Macedonian messengers, Alexander decided to take the city.

Duel of Engineering

Alexander Attacking Tyre from the Sea, an etching by Antonio Tempesta from The Deeds of Alexander the Great in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Undeterred by the natural defenses of the island fortress of Tyre, Alexander instructed his men to build a mole through the harbor to support a bridge. When the Tyrians attacked with archers, the Macedonians held up cured animal skins to screen their workers. The Tyrians responded by sending a blazing kamikaze boat crashing into the mole and bridge construction and setting it on fire. The Macedonians restarted construction, soon protected by the arrival of their fleet. Alexander mounted his siege materials onto his ships to harass the walls, and again the Tyrians returned by sending swimmers to cut the ships’ anchor ropes, leading to one of the first uses of anchor chains.

Despite the strength of Tyre, after six months, the mole was complete, and the Macedonian army crossed over at the same time that their floating siege array brought rams and siege towers to the walls. Alexander led the charge himself, as he usually did, running across a rickety plank of wood from a siege tower onto the wall of Tyre and encouraging his men to follow. Follow him they did, and Tyre fell to the onslaught.

5. The Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE)

Relief depicting the Battle of Gaugamela, 18th century CE, National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid

The Battle of Gaugamela was a major success for Alexander. His stellar use of tactics against vastly superior numbers ended in a decisive Macedonian victory and largely decided the course of his Persian campaign. Alexander entered the battle with about 47,000 campaign-hardened soldiers. According to ancient sources, the opposing Persians numbered anywhere from 250,000 to a staggering 1,000,000 men. Modern estimates consider that exaggerated and place the number closer to 120,000, but even that leaves the Macedonians outnumbered nearly 3 to 1.

To Kill or Capture the King

Battle of Arbelles by Guillaume Courtois, 1662-1664, in the Palace of Versailles, France

Alexander knew his army could not stand up to the sheer numbers of his foes for very long. He realized his only option for victory was to quickly capture or kill the Persian king, Darius, who was stationed near the center of the Persian lines surrounded by his elite royal guard, the Immortals. Alexander’s best general, Parmenion, was charged with holding a defensive position on the left flank for as long as possible. Alexander took command of the right. With infantrymen concealed among his cavalry, he ran to the right, forcing the Persian left flank to make a decision to follow him. When he had drawn the Persian cavalry out, his men attacked, surprising them with the hidden infantry.

The tactic accomplished Alexander’s goal, pulling the Persian left and creating a gap in their lines. He reformed his Companion cavalry into a wedge formation and charged for the Persian center and for Darius. The fierce fighting drew near enough to force Darius’ retreat, and with the withdrawal of the king, the remainder of the Persian army broke and fled. Many were slaughtered as they attempted to flee. Although Darius’ escape meant that Persia officially still stood, he had no means to raise another army, and Gaugamela essentially decided the war in Alexander’s favor.

6. Persian Gate (330 BCE)

A modern view of the Persian Gate, possibly from the site of the Persian camp, 330 BCE, via Livius

After defeating Darius at Gaugamela, Alexander proceeded to move through Persia, taking possession of the major cities of the empire. He was particularly eager to make his way to Persepolis, before someone else could make off with the large treasury stored there. Alexander sent the slower-moving soldiers with the baggage train around the mountains under the command of his general, Parmenion, and moved with the quickest infantry and cavalry units through a high, narrow pass in the Zagros Mountains, known as the Persian Gates. However, the Persian general Ariobarzanes anticipated his path and positioned his army above the narrow gorge.

When the Macedonians began moving through the pass, they were fiercely assailed by the Persians above. Catapults, arrows, and stones were flung at them from above, and they were forced to withdraw for the first time in their campaign. Yet what was almost Alexander’s first defeat was turned around when some prisoners of war offered to show the Macedonians a small path around the main pass. They warned that it was rocky, narrow terrain, made slick with snow and ice, but Alexander eagerly accepted. He left the majority of the army with his general Craterus, under orders to make it appear as if the Macedonian army remained encamped and, with a smaller detachment, navigated the treacherous path around to attack from the rear. At a pre-arranged trumpet blast, Craterus led his soldiers to attack as well. The Persian forces were trapped between and either killed or forced to flee, opening the route to Persepolis.

7. The Battle of the Jaxartes (329 BCE)

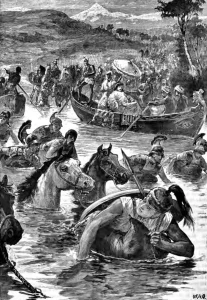

The Macedonians Crossing the Jaxartes, from Cassell’s Illustrated Universal History by Edmund Ollier, 1882, London

Although the Battle of Jaxartes may not number among Alexander’s most spectacular victories in terms of size and importance, it was an impressive example of his tactical skills. The battle took place at the northernmost limits of Alexander’s kingdom after his conquest of Persia. He had little desire to expand further north, but nomadic Scythian warriors began to harass the Macedonians on the northern border. Alexander could not withdraw from his ambitions in the south without handling this threat, for reputation as much as anything else.

The Jaxartes was a river, one the Macedonians had to cross in order to engage the Scythian warriors, but they became vulnerable to bowshots about halfway across. Alexander ordered essentially suppressing fire from his catapults on their bank in order to keep the archers at bay. The attack worked, and kept the Scythians from bow range until Alexander’s own archers had landed on the bank. They now provided cover for the cavalry and the infantry to land as well. Practically no organized nation had managed to pin down and defeat a nomadic army, as their mobility made it possible for them to quickly retreat and disperse as soon as it became necessary. However, Alexander sent a small group of mounted spearmen, almost as a sacrificial force in order to provoke the Scythians to attack.

Successful Deception

This was a move that would never have worked in the Scythian warrior society, and they didn’t see through the trick, instead falling for the bait and surrounding the small Macedonian detachment. The attack locked them in position, and Alexander was able to advance swiftly with the rest of his army. The “sacrificial force” now became a key part of the battle, blocking the Scythians’ escape, and Alexander’s infantry held the wings. It was a major loss for the Scythians. The few that did manage to flee the battlefield, only escaped further pursuit because Alexander was still weak from a wound to the neck he had taken in a skirmish shortly before the battle, and he could not ride a horse for a long period.

8. Sogdian Rock (327 BCE)

Coin portrait of Alexander the Great, 305-281 BCE, via the British Museum

The assault on the Sogdian Rock was a success of both innovation and psychological tactics. After the defeat of Darius himself, Alexander was still faced with ongoing resistance from Darius’ former commanders and soldiers. In Sogdiana, north of Bactria, he found an organized resistance holed up in a mountain fortress known as the Sogdian Rock. It was a mountain cave refuge with sheer cliff sides all around and late spring snows creating even more treacherous conditions. The defenders taking shelter there felt entirely secure, and shouted down taunts at the Macedonians, telling them they would need soldiers with wings to be able to take the rock.

Inflamed at the challenge, Alexander sought 300 of his fittest soldiers and those with climbing experience, and he offered them huge rewards, twelve talents for the first man to summit the rock — a massive sum for a regular soldier — and large prizes for the runner-ups as well. The men used rope to harness themselves in groups and metal tent pegs as pitons and began the climb in the dead of night. At least 30 fell to their deaths, but in the morning, those who survived the climb signaled to Alexander from the top of the peak. He sent a messenger back to the enemy, demanding their surrender once again and responding that he had found soldiers with wings. Terrified by the sight of the Macedonians above them, they surrendered, even though they would have easily outnumbered the small force that had actually managed to scale the heights.

9. Hydaspes (326 BCE)

The Victory of Alexander over King Porus, by Charles-Andre Vanloo, 1738, in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Alexander’s largest battle in India was fought on the shores of the Hydaspes River. For several days leading up to the battle, the Macedonian army had been encamped across the river from the Indian forces under King Porus. After finding a suitable crossing point, Alexander embarked on a series of deceptions to lull the Indian forces into a sense of false security, including declaring his intent to wait until winter to cross, sending frequent loud detachments of soldiers up and down the river, and even dressing one of his commanders in his own armor to fake his presence in the main camp. At the same time, he himself was busy planning at the proposed crossing point.

Across the River

Alexandre et Porus by Alexander Le Brun, 1672-1673 in the Louvre, Paris

With these tactics, Alexander was able to successfully sneak his boats to the crossing point. He was also able to get the majority of his army across the Hydaspes River before King Porus could respond to his sentries’ alarms and send men to contest the crossing. By the time the full force of the Indian army had arrived, the Macedonians had been able to draw up their battle lines and meet them on even ground. Through careful maneuvering, Alexander split the Indian army, forcing them to fight on two fronts not of their own choosing. The Macedonians then managed to harass the Indians’ mounted elephants, pushing them into a frenzy and then forcing the Indian infantry and cavalry back into their own panicked elephants. The resulting slaughter was horrific and left approximately 23,000 of Porus’ soldiers dead on the field.

Porus himself, badly wounded, was captured, but he and Alexander discovered a mutual respect and admiration for one another, to the point that Alexander reinstated Porus as a client king under his rule, giving Porus back all of the lands he had lost and even granting him further territory. Porus remained a loyal ally of Alexander until the young Macedonian king’s death.

10. Siege of Mallia (326 BCE)

Alexander the Great Wounded by Francesco Albani in the Public Domain, now in private collection, via ArtAuthority.net

On the tail end of their campaign through India, the Macedonians engaged in several skirmishes and battles with a tribe known as the Mallians. Their clash culminated in a siege on the Mallian stronghold. By the time they assaulted the town, Alexander’s soldiers were exhausted and ready to head home. When ordered to place ladders and climb the walls, they hesitated. To encourage them forward, Alexander leaped to the front and began scaling the ladders himself, emerging on the walls alone and exposed to enemy arrows. Realizing his precarious position, Alexander quickly decided that his best course of action was simply to leap down into the city. If he stayed on the wall, he was sure to be killed, and if he retreated, it would be shameful and disheartening to his men.

Seeing their beloved king jump alone into the enemy citadel, the Macedonian army panicked and began hurling themselves up the ladder. Unfortunately, in their fearful alarm, they overloaded the ladders and broke them. Three to four men who had managed to reach the walls before the ladders broke jumped down into the citadel just in time to see Alexander, who had been fiercely fighting off the enemy with his back to a large tree trunk, fall to a large arrow through the chest that nicked his lung. The soldiers surrounded their king and fended off his attackers, each one slowly falling, killed, or wounded. However, they managed to protect Alexander long enough that the army, now frenzied with worry over his state, managed to practically claw their way into the city. Amazingly, Alexander managed to survive the wound and continue his journey back to Babylon with his loyal and very relieved soldiers.