Nine Conflicts That Shaped Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire was built by conquest and destroyed by war. Over two centuries, several battles defined the course of both the Persian Empire and the entire ancient world.

Feb 24, 2021 • By Edd Hodsdon, BA Professional Writing, member Canterbury Archaeological Trust

Detail from Battle of Arbela (Gaugamela), Charles Le Brun, 1669 The Louvre; The Fall of Babylon, Philips Galle, 1569, via Metropolitan Museum of Art; Alexander mosaic, c. 4th-3rd Century BC, Pompeii, National Archaeological Museum of Naples

At the height of its power, the Achaemenid Empire stretched from India in the east to the Balkans in the west. Such a massive empire could not have been built without conquest. Several pivotal battles across ancient Iran and the Middle East built the Persian Empire into the world’s first superpower. However, even the mightiest empire can fall, and several legendary battles brought Persia to its knees. Here are the nine battles that defined the Achaemenid Empire.

The Persian Revolt: The Dawn Of The Achaemenid Empire

Engraving of Cyrus the Great, Bettmann Archive, via Getty Images

The Achaemenid Empire began when Cyrus the Great rose up in revolt against the Median Empire of Astyages in 553 BC. Cyrus hailed from Persia, a vassal state of the Medes. Astyages had a vision that his daughter would give birth to a son who would overthrow him. When Cyrus was born, Astyages ordered him to be killed. He sent his general, Harpagus, to carry out his order. Instead, Harpagus gave the infant Cyrus to a farmer.

Eventually, Astyages discovered Cyrus had survived. One of his advisors counseled him not to kill the boy, who he instead accepted into his court. However, Cyrus did indeed rebel when he came to the Persian throne. With his father Cambyses, he declared Persia’s separation from the Medes. Enraged, Astyages invaded Persia and sent Harpagus’ army to defeat the young upstart.

But it had been Harpagus who had encouraged Cyrus to rebel, and he defected to the Persians, along with several other Median nobles. They delivered Astyages into Cyrus’ hands. Cyrus took Ecbatana, the Median capital, and spared Astyages. He married Astyages’ daughter and accepted him as an advisor. The Persian Empire was born.

The Battle Of Thymbra And The Siege Of Sardis

Lydian Gold Stater coin, c. 560-46 BC, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Having taken over Media, Cyrus turned his attention to the wealthy Lydian empire. Under their king, Croesus, the Lydians were a regional power. Their territory covered much of Asia Minor up to the Mediterranean and bordered the nascent Persian Empire in the east. The Lydians were one of the first civilizations to mint coins from pure gold and silver.

Croesus was Astyages’ brother-in-law, and when he heard of Cyrus’ actions, he swore revenge. It’s unclear who attacked first, but what is certain is that the two kingdoms clashed. Their initial battle at Pteria was a draw. With winter coming and the campaign season over, Croesus withdrew. But rather than returning home, Cyrus pressed the attack, and the rivals met again at Thymbra.

The Greek historian Xenophon claims that Croesus’ 420,000 men vastly outnumbered the Persians, who numbered 190,000. However, these are likely exaggerated figures. Against Croesus’ advancing cavalry, Harpagus suggested that Cyrus move his camels in front of his lines. The unfamiliar scent startled Croesus’ horses, and Cyrus then attacked with his flanks. Against the Persian onslaught, Croesus retreated into his capital, Sardis. After a 14 day siege, the city fell, and the Achaemenid Empire took over Lydia.

The Battle Of Opis And The Fall Of Babylon

The Fall of Babylon, Philips Galle, 1569, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

With the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BC, Babylon became the dominant power in Mesopotamia. Under Nebuchadnezzar II, Babylon experienced a golden age as one of the most famous cities of ancient Mesopotamia. At the time of Cyrus’ attack on Babylonian territory in 539 BC, Babylon was the only major power in the region that wasn’t under Persian control.

King Nabonidus was an unpopular ruler, and famine and plague were causing problems. In September, the armies met at the strategically important city of Opis, north of Babylon, near the Tigris river. Not much information remains about the battle itself, but it was a decisive victory for Cyrus and effectively annihilated the Babylonian army. The Persian war machine was proving difficult to oppose. They were a lightly armed, mobile force that favored the use of cavalry and overwhelming volleys of arrows from their famed archers.

After Opis, Cyrus besieged Babylon itself. Babylon’s impressive walls proved almost impenetrable, so the Persians dug canals to divert the Euphrates river. While Babylon was celebrating a religious feast, the Persians took the city. The last major power rivaling the Achaemenid Empire in the Middle East was now gone.

The Battle Of Marathon: The Persians Taste Defeat

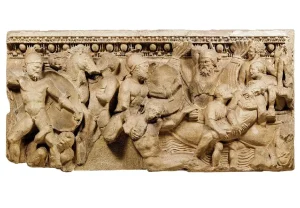

Relief from Roman sarcophagus of Persians fleeing Marathon, c. 2nd century BC, Scala, Florence, via National Geographic

In 499 BC, the wars between the Achaemenid Empire and Greece began. After their involvement in the Ionian Revolt, the Persian king Darius the Great sought to punish Athens and Eretria. After burning Eretria to the ground, Darius turned his attention to Athens. In August 490 BC, around 25,000 Persians landed at Marathon, 25 miles north of Athens.

9000 Athenians and 1000 Plataeans moved to meet the enemy. Most of the Greeks were hoplites; heavily-armed citizen soldiers with long spears and bronze shields. The Greeks dispatched the runner Pheidippides to request aid from Sparta, who refused.

A five-day stalemate developed as the two sides were both reluctant to attack. Miltiades, an Athenian general, devised a risky strategy. He spread out the Greek lines, intentionally weakening the center, but reinforcing his flanks. The Greek hoplites ran towards the Persian army, and the two sides clashed.

The Persians held firm in the center and almost broke the Greeks, but the weaker Persian wings collapsed. Hundreds of Persians drowned as they were driven back to their ships. Pheidippides ran the 26 miles back to Athens to announce victory before dying of exhaustion, forming the basis for the modern-day marathon event.

The Battle of Thermopylae: A Pyrrhic Victory

Leonidas at Thermopylae, Jacques-Louis David, 1814, via The Louvre, Paris

It would be almost ten years before the Achaemenid Empire attacked Greece again. In 480 BC, Darius’ son Xerxes invaded Greece with a huge army. After flooding the land with overwhelming numbers, Xerxes met a Greek force at the narrow pass of Thermopylae, led by the Spartan king Leonidas. Contemporary sources put Persian numbers in the millions, but modern historians estimate that the Persians fielded around 100,000 troops. The Greeks numbered around 7000, including the famous 300 Spartans.

The Persians attacked for two days, but could not use their numerical advantage in the narrow confines of the pass. Even the mighty 10,000 Immortals were pushed back by the Greeks. Then a Greek traitor showed the Persians a mountain pass that would allow them to encircle the defenders. In response, Leonidas ordered the majority of the Greeks to retreat.

The 300 Spartans and a few remaining allies fought valiantly, but the Persian numbers eventually took their toll. Leonidas fell, and the stragglers were finished off with volleys of arrows. Although the Spartans were annihilated, their spirit of defiance galvanized the Greeks, and Thermopylae became one of the most legendary battles of all time.

The Battle Of Salamis: The Persian Empire In Dire Straits

‘Olympias’; a reconstruction of a Greek trireme, 1987, via Hellenic Navy

Following the Persian victory at Thermopylae, the two sides met once again in the famous naval battle of Salamis in September 480 BC. Herodotus numbers the Persian fleet at around 3000 ships, but this is widely accepted as a theatrical exaggeration. Modern historians put the number between 500 and 1000.

The Greek fleet could not agree on how to proceed. Themistocles, an Athenian commander, suggested holding a position in the narrow straits at Salamis, off the coast of Athens. Themistocles then sought to goad the Persians into attacking. He ordered a slave to row to the Persians and tell them that the Greeks were planning to flee.

The Persians took the bait. Xerxes watched from a vantage point above the shore as the Persian triremes crammed into the narrow channel, where their sheer numbers soon caused confusion. The Greek fleet surged forward and rammed into the disorientated Persians. Constricted by their own overwhelming numbers, the Persians were massacred, losing around 200 ships.

Salamis was one of the most significant naval battles of all time. It changed the course of the Persian Wars, dealing a massive blow to the mighty Persian Empire and buying the Greeks some breathing room.

The Battle Of Plataea: Persia Withdraws

Frieze of Archers, c. 510 BC, Susa, Persia, via The Louvre, Paris

After the defeat at Salamis, Xerxes retreated to Persia with the majority of his army. Mardonius, a Persian general, remained behind to continue the campaign in 479. After a second sacking of Athens, a coalition of Greeks pushed the Persians back. Mardonius retreated to a fortified camp near Plataea, where the terrain would favor his cavalry.

Unwilling to be exposed, the Greeks halted. Herodotus claims the total Persian force numbered 350,000. However, this is disputed by modern historians, who put the figure at around 110,000, with the Greeks numbering around 80,000.

The stalemate lasted for 11 days, but Mardonius constantly harassed the Greek supply lines with his cavalry. Needing to secure their position, the Greeks began to move back towards Plataea. Thinking they were fleeing, Mardonius seized his chance and sallied forth to attack. However, the retreating Greeks turned and met the advancing Persians.

Once again, the lightly armed Persians proved no match for the more heavily armored Greek hoplites. Once Mardonius was killed, Persian resistance crumbled. They fled back to their camp but were trapped by the advancing Greeks. The survivors were annihilated, ending the Achaemenid Empire’s ambitions in Greece.

The Battle Of Issus: Persia Versus Alexander The Great

Alexander mosaic, c. 4th-3rd Century BC, Pompeii, via the National Archaeological Museum of Naples

The Graeco-Persian Wars finally ended in 449 BC. But over a century later, the two powers would clash once again. This time, it was Alexander the Great and the Macedonians who took the fight to the Achaemenid Empire. At the River Granicus in May 334 BC, Alexander defeated the army of a Persian satrap. In November 333 BC, Alexander came face to face with his Persian rival, Darius III, near the port city of Issus.

Alexander and his famous Companion cavalry attacked the Persian’s right flank, carving a path towards Darius. Parmenion, one of Alexander’s generals, struggled against the Persians attacking the Macedonian’s left flank. But with Alexander bearing down on him, Darius chose to flee. The Persians panicked and fled. Many were trampled trying to escape.

According to modern estimates, the Persians lost 20,000 men, while the Macedonians only lost around 7000. Darius’ wife and children were captured by Alexander, who promised he would not harm them. Darius offered half the kingdom for their safe return, but Alexander refused and challenged Darius to fight him. Alexander’s resounding victory at Issus signaled the beginning of the end for the Persian Empire.

The Battle Of Gaugamela: The End Of The Achaemenid Empire

Detail from Battle of Arbela (Gaugamela), Charles Le Brun, 1669, via The Louvre

In October 331 BC, the final battle between Alexander and Darius took place near the village of Gaugamela, close to the city of Babylon. By modern estimates, Darius gathered between 50,000 and 100,000 warriors from all corners of the vast Persian Empire. Meanwhile, Alexander’s army numbered around 47,000.

Camped a few miles away, Alexander captured a Persian scouting party. Some escaped warning the Persians, who spent all night waiting for Alexander’s attack. But the Macedonians did not advance until the morning, rested and fed. By contrast, the Persians were exhausted.

Alexander and his elite troops attacked the Persian’s right flank. To counter him, Darius sent his cavalry and chariots to outmaneuver Alexander. Meanwhile, the Persian Immortals battled the Macedonian hoplites in the center. Suddenly, a gap opened in the Persian lines, and Alexander charged straight for Darius, eager to finally capture his adversary.

But Darius fled once again, and the Persians were routed. Before Alexander could capture him, Darius was kidnapped and assassinated by one of his own satraps. Alexander crushed the remaining Persians, then gave Darius a royal burial. Alexander was now the undisputed King of Asia as the Hellenistic World replaced the once mighty Achaemenid Empire.