327–325 BCE saw the furthest and final conquests in India by Alexander the Great.

After conquering most of the Achaemenid Empire Alexander the Great turned his attention to India. Here on the Indian subcontinent, he would fight some of the hardest battles of his career.

With the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire all but complete, Alexander the Great continued to march his armies eastwards into the Indian subcontinent. The Achaemenid Empire had established at least two satrapies in the Indus River Valley. Moreover, the Indian subcontinent was a fabulously wealthy land that few Greeks or Macedonians had ever seen. Yet, the various rulers of India were also powerful warlords who commanded enormous armies and would not easily be defeated by Alexander the Great. As a result, there, the Macedonians would face their most arduous of campaigns. In the end, the conquest of India was to prove too much, and Alexander the Great was forced to turn back.

India in the Age of Alexander the Great

Indian Warriors (Sattagydian, Gandharan, Hindush), Naqsh-e Roastam Reliefs of Xerxes I, c.480 BCE, via Wikimedia Commons

The invasion of India by Alexander the Great was limited to the area of the Indus River Basin. In the decades prior to the invasion, the Achaemenid Empire had controlled most of the region, but evidence of Achaemenid rule east of the Indus River was nonexistent. Most of the region was ruled by small states centered around the dominance of a particular tribe. These states had recognized Achaemenid overlordship and supplied troops to the Achaemenid Empire’s armies. This was a highly urbanized region with extensive agricultural cultivation and well-established trade routes. There were also some far less developed communities in areas around the forests, deserts, and coasts.

Greek accounts make no mention of Buddhism, temples, or even religion. The only reference to the caste system is the Brahmans, who are described not as priests but as philosophers and advisors to the kings and princes of India. Greek observers also witnessed Sati, the practice of widows immolating themselves on their husband’s funeral pyres, the ritual exposure of dead bodies to vultures, and the practice of slavery. However, the Greeks also recognized cultural differences between different groups of Indians in different parts of the Indus River Valley. Perhaps what made the greatest impression, though, were the Indian medical sciences which in several areas were more advanced than those of the Greeks.

Completing the Conquest of the Achaemenid Empire: The Invasion of India

Bihr Mound, Gandharan/Achaemenid ruins of Taxila, c. 800-525 BCE, via UNESCO World Heritage Center

The invasion of India was in many ways the next logical phase in Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Achaemenid Empire. This was, after all, the only remaining part of the Achaemenid Empire that had not submitted to him. In 327 BCE, Alexander summoned the chieftains of the satrapy of Gandhara to submit to him. Ambhi (in Greek Omphis), ruler of Taxila, complied and would lead his forces alongside Alexander the Great during the invasion. Alexander married Roxana to cement his relations with the satraps in Central Asia and secure his supply routes and lines of communication. He also detached his general Amyntas with 3,500 cavalry and 10,000 infantry to guard the region before embarking on his campaign.

Between May 327 BCE and March 326 BCE, Alexander the Great began the first phase of his invasion with what is now known as the Cophen Campaign. His goal was to secure his line of communication by capturing fortresses of the Aspasioi, Guraeans, and Assakenoi tribes in the Kunar valley of modern Afghanistan and the Panjkora (Dir) and Swat valleys of modern Pakistan. The Aspasians were the first to be conquered and Alexander the Great took their cities after a series of sharp engagements during which both he and his general Ptolemy were wounded; though Ptolemy killed the Apasian king. The Guraeans then razed their cities and attempted to catch the Macedonians off guard but were defeated. Next, the Assacenians were defeated in a tough battle and their king was slain. However, Cleophis, the mother of the Assacenian king, refused to surrender the capital city of Massaga, which only fell after a tough siege. Finally, Alexander took Aornus, which proved to be his last great siege and secured his lines of communication across the Hindu Kush.

The Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BCE)

Alexander and Porus, by Vincenzo Camuccini, 1771-1844 From The Metropolitan Museum of Art

After debouching from the Hindu Kush, Alexander the Great’s army linked up with the forces of king Ambhi of Taxila. Continuing their march to the east, they entered the territory of king Porus (possibly Paurava), who ruled between the Hydaspes and Acesines (Chenab) rivers in the Punjab region. Porus and Ambhi had long been rivals and now Porus was determined to defend his kingdom. Against Alexander the Great’s army of 40,000 infantry, 5-7,000 cavalry, and roughly 5,000 allied Indians, Porus mustered 20-50,000 infantry, 2-4,000 cavalry, 1,000 chariots, and 85-200 war elephants. Both armies encamped on opposite banks of the Hydaspes (Jhelum) river, which was so deep and fast that whichever side attempted to attack across it would likely be destroyed by the other. For several days Alexander moved his cavalry up and down the riverbank looking for a place to cross while Porus shadowed him. Eventually, Alexander was able to move a force across the river while his general Craterus distracted Porus’ forces.

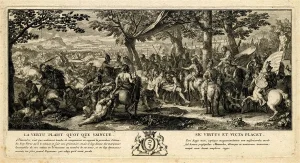

Landscape with King Porus wounded brought before Alexander the Great, by Charles Le Brun, 1695, via the British Museum

Porus soon discovered Alexander had crossed the river and dispatched his son and chariots to try and stop him. However, they were defeated, and Porus’ son was killed. When the main battle began Alexander the Great sent his horse archers to attack the Indian cavalry on the right wing, while his Companion cavalry attacked the Indian cavalry on the left. Seeing their compatriots on the left in trouble, the Indian cavalry on the right rode to their aid. They were followed by the rest of the Macedonian cavalry, attacked from the rear, and scattered. The Indian war elephants and infantry then attacked and were met by the Macedonian phalanx. A tough hand to hand battle ensued with each side launching repeated attacks and suffering many casualties. Eventually, Craterus arrived with reinforcement just as Alexander the Great was able to attack the rear of the Porus’ army with his cavalry, finally breaking it and effectively ending the Battle of the Hydaspes.

An Army Revolt Sends Alexander the Great Home

Bronze statuette of a rider (Alexander) wearing an Elephant skin, Hellenistic, 3rd Century BCE, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Macedonians suffered heavy casualties during the battle of the Hydaspes. Nonetheless, when Porus surrendered, Alexander the Great spared his life, returned his throne, and helped him reconcile with Ambhi out of admiration for his bravery and prowess. An able local ruler also helped Alexander administer his territory. During the battle, Alexander the Great’s horse, Bucephalus, had suffered a mortal wound. Having first received Bucephalus as a teen and ridden him across Asia, Alexander the Great founded the city of Alexandria Bucephalus in his honor. Alexander the Great then marched on receiving the surrender of additional kings until near the Hyphasis (modern Beas) river, his men finally refused to go further. They mutinied and begged Alexander to turn back and allow them to return home.

The Hyphasis river is not too distant from the Ganges, which the Macedonians had been told was incredibly wide and deep, making any crossing difficult. It also sat on the border of the vast and powerful Nanda Empire. Having been mauled in battle by Porus’ army, Alexander the Great’s Macedonians were utterly demoralized by the prospect of facing another more powerful Indian army. Unable to convince his men to march further on, Alexander sulked in his tent for several days until the soldiers begged him to lead them once more and professed their love and loyalty. Thus reconciled, Alexander and the Macedonian army began the long march west. Interestingly, the Nanda king, Dhana Nanda would only rule for a few more years as he was overthrown by Chandragupta Maurya, founder of the Mauryan Empire, in 322 BC.

Alexander the Great’s Final Wounds

Tetradrachms of deified Alexander the Great wearing an Elephant skin to symbolize his conquest of India, Hellenistic Egypt, 319-310 BCE, via the Museum of Fine Arts Boston

After the mutiny, Alexander the Great marched his army down river along the Hydaspes to Acesine in order to define the eastern limits of his empire. However, the Mallians and Oxydracians, though traditionally enemies, had formed an alliance to oppose the Macedonians. Their combined forces were said to number 90,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 900 chariots. Unbeknownst to the Indians, Alexander the Great was willing to wage war year-round, which was unthinkable to most ancient armies. Therefore, the Indians were caught off guard by the speed of Alexander’s advance. Not wanting to let any Indians escape, Alexander carried out a sophisticated campaign of river crossings and rapid marches with different corps of his army acting independently. Soon the alliance between the Mallians and Oxydracians collapsed as they could not agree on who should command or what their strategy should be, and they retreated into their capitals.

Finally, Alexander the Great approached the capital of the Mallians, possibly the modern city of Multan. The Mallians attempted to meet Alexander the Great in the field one last time but were again defeated. When the Macedonians approached the city, the Mallians abandoned the outer fortifications and retreated into the city. Alexander set his men to undermine the walls but became impatient. He seized a ladder and scaled the walls with two other soldiers. The rest of the Macedonians attempted to follow but so crowded the ladders that they broke under the weight. When the Mallians realized who Alexander was and how vulnerable he was, they desperately sought to kill him. Although the Macedonians begged Alexander to jump off the wall onto their shields, he instead rushed further into the citadel. There, he killed the Mallian leader but was shot in the lung with an arrow. The Macedonians then broke into the citadel and rescued Alexander, whom they carried back for medical treatment and proceeded to massacre the Mallians, who they believed had killed their king.

Legacy of Alexander the Great in India

Stupa drum panel showing a drinking scene, Gandhara(Pakistan) 1st-2nd Century BCE, via the British Museum

After hovering near death for four days, Alexander recovered from his wound and received the surrender of the surviving Mallians. He then continued down the river, conquering the remaining Indians tribes in his path. Upon reaching the coast, Alexander the Great commissioned a fleet to explore the Persian Gulf and marched the rest of his army back to Babylon across the brutal Gedrosian desert. In India, he left Peithon and Eudemus as his satraps alongside Porus and Ambhi with a large army. After Alexander the Great’s sudden death in 323 BC, Porus was assassinated by Eudemus, who was then executed by another of Alexander’s former generals, while Peithon was killed in battle, and Ambhi lost his kingdom to Chandraguta Maurya.

Marble portrait head of Alexander the Great, Hellenistic, 2nd-1st Century BCE, via the British Museum

Alexander the Great’s invasion of the Achaemenid Empire’s territory in the Indian subcontinent brought two vastly different cultures into direct contact for the first time. Greek colonies were established, so that cultural contact and exchange continued long after Alexander the Great departed. As a result, there was a lively exchange of ideas about philosophy, religion, medicine, science, mathematics, geography, warfare, trade, and art. The Indo-Greek artworks that have survived form their own distinct style and are some of the most impressive pieces to have been produced during this period. Stories of India were passed down through the centuries in Europe so that Alexander’s conquests assumed mythic proportions and exerted a profound influence. It would not be unreasonable to therefore conclude that Alexander the Great’s time in India was the most important aspect of his legacy.