How Did the Universe Start? Three Myths of Greek Creation

There is no singular creation myth in Greek mythology. Homer, Hesiod, and Orphism all differ in their accounts of how the world, the gods, and humans came to be.

Birth of Venus by William Bouguereau, 1879, via Museum d’Orsay and Olympus; with The Battle of the Giants by Francisco Bayeu, 1768, via Museo Nacional del Prado

Creation myths are a fundamental part of all religions and mythologies. They explain how the world was created, and they lay the foundations for a well-formed mythology. In some cultures, the story of creation is concrete and well-recorded, such as in the Book of Genesis used by the Abrahamic faiths. However, in ancient Greece, the creation myths, as with many other Greek myths, vary drastically between different traditions. Hesiod provides the most complete and well-known creation myth, while the Homeric tradition creates a bridge between an older tradition and Hesiod. The Orphic tradition, or Orphism, provides a very different account of the creation of the world and mankind.

Below are the variations on the Greek creation myths, as told through the traditions of Hesiod, Homer, and Orphism.

Greek Creation Myths: Hesiod And The First Creation Myth

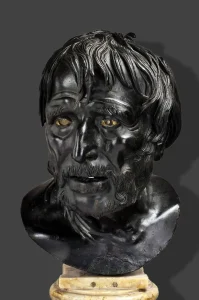

Pseudo-Seneca (now thought to be a bust of Hesiod), via Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

The first complete account of the Greek creation myths can be found in Hesiod’s Theogony, in which he describes the creation of the world, the gods, and mankind. This poem is the most prominent of the three, as well as the longest-written story of the creation myths. Starting with a hymn for the Muses, the Theogony tells the story of the universe starting from when there was just one primordial condition, to the creation of women. Hesiod’s other poem, Works and Days, contains myths about the creation of man and woman, but it is not, as a whole, a creation myth.

Hesiod and the Muse by Gustave Moreau, 1891, via Museum d’Orsay

In the beginning, there was only Chaos, the primordial condition. The prominence of Chaos as the primordial condition and preceding the primordial beings is significant mythologically and later philosophically. From Chaos emerged Gaia (Earth), Tartarus (Underworld), Eros (Desire), Erebus (Darkness), and Nyx (Night). They then created the rest of the primordial beings, such as Hemera (Day), Uranus (Sky or Heavens), and Pontus (Sea).

Gaia took her son, Uranus, as her husband and gave birth to the Twelve Titans, as well as six monstrous children. Uranus imprisoned the monstrous children, which greatly angered Gaia. In order to punish Uranus, Gaia asked her Titan children to attack their father with a sickle. This began the cycle of sons overthrowing fathers, known as the ‘Succession Myth.’ The ‘Succession Myth’ is repeated several times in the Theogony, as well as within Greek mythology.

Birth of Venus by William Bouguereau, 1879, via Museum d’Orsay

Kronos, the youngest Titan, castrated and overthrew his father on behalf of his mother, and the Titans took their place as the rulers of the universe. When Kronos castrated his father, Uranus’ genitals fell into the sea and transformed into sea foam. From this sea foam emerged Aphrodite, at either the island of Cythera or Cyprus, which were centers of worship for the goddess.

Rhea and Cronus, Greco-Roman marble bas-relief, Capitoline Museums

Kronos and Rhea then had six children: Hestia, Poseidon, Hera, Hades, Demeter, and Zeus. Just as he overthrew his father, Kronos knew that one of his children was fated to overthrow him and the Titans as the rulers of the universe. In order to prevent this, Kronos devoured his first five children once born, much to the anger of Rhea. She, along with Gaia who was angry that Kronos kept his monstrous siblings imprisoned, hatched a plan to overthrow him. When Zeus was born, Rhea hid him and gave Kronos a rock to swallow instead. Zeus then was able to grow up hidden from his father. Eventually, with the help of other Titans, Rhea and Zeus forced Kronos to vomit up his other children.

Zeus and his siblings, along with Gaia’s monstrous children, battled the Titans in what is known as the Titanomachy. The war lasted ten years and ended with the establishment of the Olympian gods as rulers over the heavens and earth. The Titans who sided with the Olympian gods were rewarded, while the rest were thrown into Tartarus. The Titanomachy is a continuation of the ‘Succession Myth,’ as Zeus overthrows his father. According to this tradition, Zeus was fated to be overthrown by his son through Metis, which he circumvented by swallowing her and birthing Athena himself.

Pandora by Odilon Redon, 1912 via National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection

Although the Theogony does not depict the creation of man, it does tell of the creation of woman. Pandora, the first woman, was created as a punishment for man by Zeus and the gods. Prometheus, one of the Titans who sided with the Olympian gods, disobeyed Zeus in order to help man. Zeus decides to punish both Prometheus and man for his indiscretions. Thus, the gods, specifically Hephaestus and Athena, fashion Pandora, and she is sent down to mankind. Hesiod states that Pandora, and womankind in general, were wicked and caused pain for man. With the story of Pandora, Hesiod recounts the creation myths, from the birth of the gods to early man, within the Theogony.

In Works and Days, his other poem, Hesiod states that mankind was created multiple times by both the Titans and the Olympian gods. The Titans forged the Golden Age of humans, and the Olympian gods the Silver Age, Bronze Age, Age of Heroes, and Iron Age. Hesiod recounts what happened to each of the generations of man until the current generation, the Iron Age. The Age of Heroes is the generation of humans within Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Works and Days thus completes the Hesiodic creation myth.

Homer: Differing Genealogies For The Gods

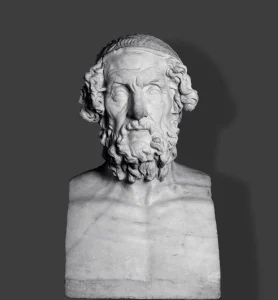

Portrait Bust of Homer, 2nd Century BC via The British Museum

Homer, perhaps the most famous of the Greek poets, was a pseudo-legendary blind bard to whom the Iliad and Odyssey are attributed. It is now understood by most academics that Homer as a singular man did not exist, but rather the works attributed to him are the culmination of years of oral tradition. The Homeric tradition does not have a fully developed creation myth, but it does mention the creation of the gods. There are two main ways in which the Homeric and Hesiodic traditions diverge.

Female Figures from the Parthenon, 438-432 BC, via The British Museum

In the Iliad, Homer’s epic about the Trojan War, Aphrodite is the daughter of Zeus and Dione. In Book V, Aphrodite is described as running to her mother, Dione, after being injured in battle. This represents a very different origin for Aphrodite, who Hesiod describes as being born from sea foam after the castration of Uranus. The Hesiodic tradition is the version of Aphrodite that was more widely known and more widely accepted.

Jupiter Beguiled by Juno on Mount Ida by James Barry, 1799, via The Graves Gallery

Perhaps more disparate is the Homeric tradition regarding the origins of the gods. During the “Deception of Zeus” in Book XIV, Hera twice refers to Oceanus and Typhus as the primordial couple instead of Gaia and Uranus. According to the Theogony, Oceanus and Typhus were the Titans who birthed the river and sea deities. These two references show a large divide between the Hesiodic and Homeric traditions about the Greek creation myths.

The tradition of Oceanus and Typhus, two water deities, mentioned within the Iliad could be a reference to an earlier Greek creation myth, the myth of Eurynome. In this creation myth, Eurynome and Ophion emerged from chaos and created a cosmic egg from which the world and the gods were created. There are links between Oceanus and Typhus and the Eurynome creation story, and the Homeric tradition could be seen as a continuation of this creation myth. These traditions pre-date Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days, which would account for the differences between creation myths.

The Orphic Tradition: A Very Different Creation Myth

Orpheus and Eurydice by Auguste Rodin, 1893, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Orphism was a Greek mystery religion said to be founded by Orpheus, the legendary poet. The Orphic creation myths and religion as a whole revolved around the god Dionysus and his resurrection, along with the reincarnation of the soul. There is no one binding text for the religion, but hymns and accounts of the religion allow us to understand its creation myths.

As there is no singular text in Orphism, many variations of this creation myth exist. Many scholars believe that Orphism was influenced by Eastern ideas, which is in line with the belief that Dionysus was a foreign deity.

In the Orphic creation myth, Chronos, the primordial personification of time, creates Aether (Sky), Chaos, and a cosmic silver egg. In this way, the Orphic tradition of a cosmic egg is similar to the creation myth of Eurynome. It is important to note that Chronos and Kronos are two separate entities. From the cosmic egg emerged Phanes, also known as Eros, Phanes-Dionysus, and Protogynous. Phanes then births what in Hesiod are the primordial beings, first Nyx and then Gaia, Uranus, etc. Thus, in the Orphic creation myth, it is Phanes, not Chaos, that is the creator of the world.

Bacchus by Caravaggio, 1597, via The Uffizi Gallery Museum

The key figure in Orphism, Dionysus, was originally born as Zeus and Persephone’s son and named Zagreus. Zeus named Zagreus as his successor. This marks the first divergence from the Hesiodic creation myths, which focuses on the ‘Succession Myth.’ In the Hesiodic tradition, Zeus does not want to be succeeded and circumvents being overthrown by his son.

Hera, jealous that Zagreus is named as Zeus’ successor, convinces the Titans to kill the child. The Titans tear up and eat Zagreus. As punishment, Zeus strikes the Titans with his lightning bolt, turning them into ash, and retrieves the heart of Zagreus.

In some recountings of the resurrection of Dionysus, Zeus impregnates Semele with the heart of Zagreus, and she gives birth to Dionysus. In others, Zeus implants the heart into his own thigh, from which Dionysus springs forth. There are also accounts of other deities, Athena and Apollo, playing a role in the resurrection of Dionysus and gaining a special title within the religion. The Orphic myth has similarities to the more ‘traditional’ origins of Dionysus, which always revolve around the god being born twice.

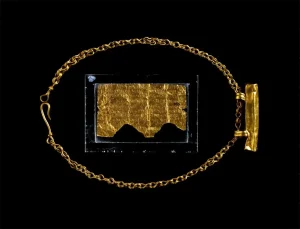

Orphic Gold Pendant, 3rd Century BC, via The British Museum

In Orphism, mankind was created from the ashes of the Titans and Zagreus. This creation story imbues mankind with an element of divinity. The Orphic tradition states that it is the soul of man that is divine — as it comes from the ashes of Zagreus, while the body is sinful and comes from the ashes of the Titans. The idea of a divine soul, as well as its reincarnation, was central to the rites and religion of Orphism.

This creation myth varies wildly from that of Hesiod, in which multiple generations of man were created by the gods. Moreover, the stark differences between the creation myths of Hesiod and Orphism can be seen as a difference between a mythological poem and a religion. The Orphic creation myth works to explain the rites and practices of the religion, whereas the Theogony is a poetic narrative.

Why Are These Creation Myths Different?

Olympus. The Battle of the Giants by Francisco Bayeu, 1768, via Museo Nacional del Prado

Religion in ancient Greece was a collection of sects, practices, and beliefs which had overlapping deities and myths. As new influences came and went, deities and stories entered into the Greek canon and created contrasting myths. The differences between the three creation myths, and the various others found in ancient Greece, can be attributed to this lack of a singular religion or source.