Titanomachy: The Bloodiest War in Greek Mythology

The fiercest battle in Greek mythology is known as the Titanomachy. Learn more about the battle between the Titans and the Olympian Gods.

The Fall of the Titans, by Dutch painter Cornelis van Haarlem, 1596–1598. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Different interpretations exist regarding the creation of the world in Greek mythology. Historians and poets have differing accounts of how the universe, along with its gods and deities, came into existence. However, there is consensus on the existence of three generations of gods: the first generation comprising Uranus and Gaia, the second consisting of Cronus and Rhea, and the third and final generation including Zeus and Hera. The transition of power from one generation to the next was not always smooth, and the most brutal conflict for the throne, known as Titanomachy, occurred between Zeus and his father Cronus.

Before the Titanomachy: The First Three Generations of Gods

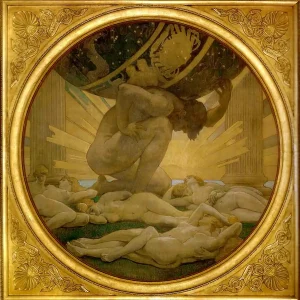

Ceiling paining of Gaia in Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, by Anselm Feuerbach, 1875, via Bild

Before delving into the Titanomachy, it is essential to establish some conceptual distinctions and explore the events preceding the battle. Firstly, we must define what a myth is and then examine the different generations that existed among the gods.

Greek myths consist of narratives that revolve around the relationships between gods and humans. Myths represent one of the oldest and earliest means for humans to explain the phenomena that they saw in the world that surrounded them. Myths also offer explanations for the origins of nature. At times when people had very little scientific knowledge about the world, myths served as stories that fulfilled the human desire for a fundamental sense of direction. In this way, myths assist individuals in finding their place within the world, making them significant in the context of human history. They provide valuable insights into the history of human thought through the millennia.

Concerning the world’s creation in Greek mythology, there are multiple theories, with three of the most “reliable” versions of the myth being attributed to Homer, Ovid, and Hesiod. Homer states that Oceanus and Tethys are the parents of all other gods. On the other hand, Ovid believes that the world emerged from Chaos, which he describes as a chaotic mass of elements from which a divine being or a higher natural force brings order to the universe.

Homer and His Guide, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1874, via Milwaukee Art Museum

The theory presented by Hesiod around 700 BCE is particularly significant. According to Hesiod, the world originated from Chaos, which he describes as a state of pure emptiness. From Chaos, the first generation of gods emerged.

In this first generation of gods, we find Uranus and Gaia. Uranus represents the male deity associated with the sky, while Gaia symbolizes the female deity associated with fertility and the earth. Their union forms the concept of the “holy marriage” or “hieros gamos”.

The Titans, who constitute the subsequent generation of gods, are the offspring of this sacred union between Gaia and Uranus. This pattern of sacred marriage continues with their offspring Cronus and Rhea, who become the parents of the third generation of gods. Another iteration of the sacred marriage occurs with the union of Zeus and Hera, who are the successors of Cronus and Rhea.

Greek mythology tells us that the most intense battle unfolds with the ascent of this third generation of gods. This battle is called the Titanomachy, and it is a result of the conflict between Zeus and his father Cronus.

What Happened During the Titanomachy?

Cronus devouring one of his sons, by Peter Paul Rubens, 17th-century, via Museo Del Prado

The Titanomachy refers to the brutal battle for supremacy in Greek mythology, wherein Zeus battled against his father Cronus. Cronus had previously dethroned his own father, Uranus, and now history seemed intent on repeating itself. Following the prophecy that one of Cronus’ own children would overthrow him, Cronus took precautions by imprisoning his siblings, known as the Titans, in a part of the underworld known as Tartarus. Cronus also decided to devour his own offspring as to avoid their rebellion.

However, Rhea, Cronus’ wife, who wasn’t very happy with the devouring of their children, managed to outwit him and save their youngest son Zeus. Rhea hid Zeus in a cave on the island of Crete, where he was raised secretly, nurtured by a goat named Amalthea. As Zeus grew to adulthood, he assumed the role of Cronus’ cupbearer, all the while concealing his true identity.

Zeus was cunning and devised a plan to trick Cronus. He prepared a concoction of drinks and potions, which made Cronus regurgitate the children he swallowed one by one: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. Once all his brothers and sisters were liberated, Zeus rallied them together and persuaded them to wage war against their father, initiating the Titanomachy.

Hades, god of the underworld, mid-2nd century CE, via Wikipedia Commons

Zeus released the Hecatoncheires and Cyclops, who had been imprisoned by his father. He sought their aid in the battle, and they agreed to support him. The Hecatoncheires fought by throwing large stones, while the Cyclops forged Zeus’s lightning bolt, which became his most famous and formidable weapon. Among the Titans, Themis and Prometheus joined Zeus, while Atlas led the Titans loyal to Cronus.

The Titanomachy ensued, lasting an entire decade. This period was marked by intense clashes between the Titans and the Olympian gods. Zeus fought from Mount Olympus, while Cronus took his stand on Otrius, a Thessalian mountain. This conflict represented a struggle for supremacy and control over the cosmos. The Titans, renowned for their immense power and strength, were a formidable opposition. However, after fierce battles and engagements, Zeus and his siblings ultimately emerged triumphant, claiming victory in the Titanomachy.

The Aftermath of the Titanomachy

Atlas and the Hesperides by John Singer Sargent, 1925, via Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Following the Titanomachy, the Titans who had fought against the Olympian gods were defeated and condemned to imprisonment in Tartarus, a dark and deep abyss within the underworld. This eternal confinement served as their punishment for daring to challenge the authority of the Olympians. However, it is worth noting that not all Titans faced the same outcome. Certain Titans, including Oceanus, Themis, and Mnemosyne, who had either helped Zeus or remained neutral and refrained from participating in the war, were allowed to retain their positions without being incarcerated in Tartarus. Although their influence and power were diminished, they continued to exist within the cosmos.

A few Titans were granted unique roles within the newly established cosmic order governed by the Olympian gods. Prometheus, renowned for his cleverness and intelligence, played a significant part in the creation of humankind and was spared from the severe punishment imposed upon the other Titans. Atlas, on the other hand, was burdened with the eternal task of bearing the weight of the heavens upon his shoulders. This penalty, often referred to as the “punishment of Atlas” or “Atlas’ curse,” has been depicted in various forms of art and literature, portraying Atlas as an enduring figure carrying the celestial spheres.

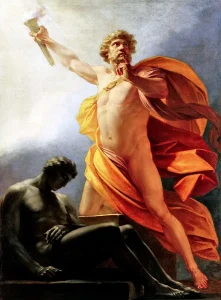

Prometheus Brings Fire, by Heinrich Friedrich Füger, 1817, via Wikipedia Commons:

Although the Titans were commonly depicted as adversaries of the Olympian gods in Greek mythology, it is crucial to recognize that their role and significance extended beyond their defeat in the Titanomachy. The Titans represented an earlier generation of divine beings associated with fundamental forces and cosmic powers. They were often linked to the natural elements such as earth, sea, and sky.

In various interpretations, the Titans were considered personifications of natural phenomena and abstract concepts. For instance, Cronus symbolized time, while Atlas represented the celestial spheres. These associations underscore the broader symbolism and mythological importance attributed to the Titans in Greek mythology. Furthermore, the tales involving the Titans continue to inspire literature, art, and popular culture. Their conflicts, relationships, and interactions with both gods and mortals have fascinated human imagination throughout history, leaving a lasting impact on various works of fiction and creative expression.

Division of Power after the Titanomachy

Sculpture showing Zeus holding a thunderbolt, via unknown artist, via Louvre

Following the Titanomachy, the victorious Olympian gods divided the universe among themselves. Zeus, as the supreme ruler, assumed the role of king of the gods and guardian of the heavens. Other gods were assigned specific realms, with Poseidon becoming the god of the sea, Hades ruling over the underworld, and various deities presiding over different aspects of the natural and supernatural world.

Mount Olympus, the highest peak in Greece that held particular mythical importance, served as the divine abode and gathering place for the gods. It was where they convened to discuss important matters and make decisions. The Olympian gods held great significance in ancient Greek society and were revered through worship, rituals, sacrifices, and prayers. Temples and sanctuaries were dedicated to them throughout Greece, and festivals and celebrations were held to honor their presence.

As immortal beings, the Olympian gods possessed powers and abilities far beyond those of mortals. They exhibited the characteristics and emotions typically associated with Greek mythological gods, with their actions reflecting their distinct personalities and the domains they ruled over.

The Titanomachy holds significant mythological importance as it represents the transition of power from the Titans to this younger generation of gods led by Zeus. It symbolizes the victory of order over chaos, a victory that would be repeated in the next episode of the story, the Gigantomachy, the battle between the triumphant Olympians and the Giants.