The Olympic Tradition of Ancient Greece: Barefoot Racing

In modern times, the Olympic Games take place in the summer and winter every four years. But where did the ancient Olympic Games originate from?

The modern Olympics have a rich history of tradition and triumph. Every four years, athletes from around the world meet to compete and celebrate extraordinary victories and outstanding feats of physical prowess. Revived in 1894 by Frenchman Pierre de Coubertin, Athens, Greece hosted the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. While they are still a spectacle of human athleticism, there are striking differences between the ancient and modern games. To understand these differences and why they matter, we first need to understand the purpose and structure of the ancient Olympic Games.

History of the Ancient Olympics

Greek Athletes Wrestling, c. 510 BCE, via worldhistory.org

Before establishing the ancient Olympic games, the ancient Greeks had a strong cultural history of athletic competitions. The ancient poet, Homer, includes several descriptions of funeral games in the Iliad and Odyssey. While the games depicted in the poems were fiction, they were likely based on similar games of Homer’s world. These competitions contained a variety of competitions, ranging from footraces to chariot races, and with a range of prizes for victors. The Archaic period (700-480 BCE) marked a moment of complex and varied athletic competitions. Oftentimes, games were a way to honor gods and heroes, establishing a connection between competition and religion.

The ancient Olympic Games were part of a religious ceremony held in honor of Zeus, the mightiest of all the Greek gods and goddesses. Held in Olympia in the western Peloponnesos, the festival attracted Greeks from different city-states, who came to honor Zeus and watch or participate in the athletic games. In the first games, held in 776 BCE, the sole winner, Koroibos of Elis, won the stadion footrace. The stadion race was about 600 feet long, and according to some sources, was the only event at the games until 724 BCE.

The sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia was the home of the ancient Olympic Games. The Olympics were no inconsequential event in ancient Greece. Before each Olympics, heralds from Elis, the city-state in which Olympia sat, traveled throughout Greece, announcing the games, inviting athletes and spectators from around Greek states and colonies, and declaring an ekecheiria — a great truce. This truce ended any tensions or conflicts and allowed for safe travel to the games. It also banned weapons in Elis.

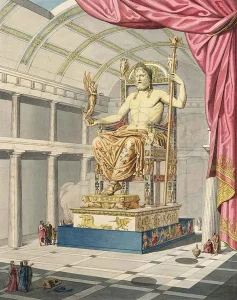

Le Jupiter olympien ou l’art de la sculpture antique, by Quatremère de Quincy, 1815, via Wikimedia Commons

Thousands of Greeks traveled to the festival to honor Zeus and the other gods. The ceremonies began two days before the competition as a convoy of Eleian officials, athletes, trainers, representatives from Greek states, and spectators began the 25-mile trek from Elis to Olympia. Upon arrival at Olympia, the athletes swore sacred oaths to “do nothing evil” against the games and that they had trained for 10 months prior. The judges also swore oaths to judge fairly, accept no gifts, and keep any information about the competitors secret.

Competitions lasted for a week in the latter days of the Olympics. The first day consisted of the oath-taking, then continued to the footraces and wrestling events for boys. In the afternoon, competitors were free to explore Olympia. Athletes competed in horse-based events and the pentathlon on the second day which ended with funeral game reenactments and performances about the victors.

On the morning of the third day, a massive ceremony took place to honor Zeus. Footraces were the main attraction of the afternoon. All contact sports were completed on the fourth day with the hoplitodromos (a footrace in which competitors wore some battle armor), finishing the day. This reminded athletes and spectators that the true purpose of the competition was to prepare men for war. Judges handed out awards on the final day of the Olympics and there were feasts and celebrations in honor of the victors.

One of the main attractions at the games was the ivory and gold statue of Zeus that sat inside the temple. At over 42 feet tall, Zeus sat enthroned, holding a statue of Nike, the goddess of victory, in his right hand and a scepter in his left. Spectators and athletes could visit the temple to make sacrifices and oaths.

Wrestling Center at Ancient Olympia, by John Karakatsanis, via Wikimedia Commons

Although the games were a major attraction for athletes and spectators, religion remained at the center of the games. During the procession from Elis to Olympia, the Hellanodikai, the men who judged the events and participated in religious ceremonies, were sprinkled with the blood of a sacrificed boar and washed in the Pierian spring. Purified, they were prepared to proceed to Olympia.

On the third day of the competition, religious leaders sacrificed 100 oxen after the completion of the athletic games. After Zeus sampled the meat (burned thigh bones and fat), the remainder was cooked and served to the spectators and participants. Athletes made offerings, prayed to various gods for assistance, and swore sacred oaths in return for success. Other gods and heroes who were also associated with the Olympics included Athena, Hermes, and Herakles.

In the earliest centuries, a sacred olive tree, the tree from which the victory wreaths were cut, marked the finish line for all events until the mid-400s. As the games grew, the site expanded and the stadium was moved to accommodate more spectators, meaning the olive tree was no longer used as the finish line. Olympia was also home to over 70 altars, offering people numerous opportunities to make sacrifices to a variety of gods.

Ancient Games at the Olympics

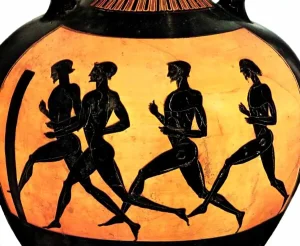

Panthenaic amphora, Unknown, 480-470 BCE, via Leuven University

Competitions at the ancient Olympics may initially seem familiar to a modern spectator, but there were several significant differences between the sports people enjoy today and what the ancients watched. One of the most jarring differences would be their uniform or lack thereof. All non-equestrian participants competed naked. Historians continue to debate the reasons for this, but some believe that this was done for ease of movement or in honor of Zeus by showing off their physical strength and physique. Assistants, or aleiptes, rubbed down athletes in olive oil before and after the competition.

Most early events were footraces. The stadion was a race of one length of the stadium track, while the diaulos was a race of two lengths. During the diaulos, athletes would turn around a post before making their way back. The hoplites or hoplitodromos was a similar event, with athletes wearing a helmet, shield, and sometimes, shin guards. The pentathlon combined five competitions into one: Discus, javelin, broad jump, a stadion race, and wrestling.

Panathenaic amphora, c 332-221 BCE, via Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Greek combat sports were much more violent than the modern versions. Pankration (a type of ancient wrestling) was exceptionally brutal. The only banned moves in this event were biting and eye gouging. Since the event only ended in surrender or death, athletes frequently suffered major injuries during combat events. Equestrian and chariot events were introduced later, between the mid 600s-400s. These events typically involved racing chariots for various lengths of the stadium.

Unlike modern athletic competitions, there was only one victor per event, with no prizes for second or third place. Victors received an olive wreath, ribbons, and palm branches as rewards for their Olympic victories. Rewards were intentionally understated to reinforce that true victory came from the athlete’s success. Although there were no cash prizes, some city-states lavished victors with cash or other worthy prizes.

Finally, there were no team events in the ancient games, nor, generally, were women allowed to watch or participate in the games. There are some women listed as victors in different local competitions, and during a festival to honor Hera, there were footraces for unmarried women that allowed women chances to participate. These events, however, were not part of the Olympics.

The Influence of the Ancient Olympics on Modern Times

Olympics flag in Victoria, by Makaristos, 2007, via Wikimedia Commons

Although there are significant differences between the ancient and modern games, the spirit of competition and unity continues today. A United Nations resolution that calls for a halt to hostilities during the Olympics and a search for a peaceful end to conflicts in the region where the Olympics are held reflects the ancient Olympic Truce. When the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, the Olympic motto, “Faster, Higher, Stronger” was changed to “Faster, Higher, Stronger — Together” to reflect the world’s unity during the pandemic and to focus on the broader message of the game.

While the modern Olympics are a secular event, the modern opening and closing ceremonies also mirror the pageantry and celebration of the feasts that bookended the week of the ancient Olympics. In ancient times, the week opened and closed with feasts and celebrations to honor the athletes and the gods. Modern opening and closing ceremonies focus on the secular nature of the games, providing a history of the host nation and a brief introduction to the next host city and country. Ancient athletes walked from Elis to Olympia with their trainers and family members, and the opening ceremonies of the modern Olympics include a parade of nations, during which each country’s athletes, trainers, and representatives walk through the stadium to celebrate the opening ceremonies.

Terracotta skyphos (deep drinking cup), attributed to the Theseus Painter, ca 500 BCE, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the lead-up to the Olympics, there is usually a torch relay that carries a flame from Olympia to the host city, culminating in the lighting of the Olympic flame during the opening ceremony. This practice, while a modern invention, draws inspiration from ancient games. Ancient Greeks lit a fire during the ancient games to commemorate Prometheus stealing fire from Zeus and gifting it to humans. Today, representatives light the Olympic torch from the altars of Zeus and Hera in Olympia before heading on a journey to the host city, connecting the ancient and modern games in a way that honors the game’s origins.

At the core of the modern Olympics are the virtues of honorable performance, courage, perseverance, and self-sacrifice. During every Olympics, spectators cheer on their country, their favorite athletes, and the unexpected underdogs as they push themselves to the brink of human physical capabilities. The competitive and celebratory spirit of the ancient games can be felt in the ceremonies, sports, and spirit of the modern games. Let the Olympics serve to remind all humans that the greatest achievements to come from these games are not fame and fortune, but rather the glory of athletic achievement, mutual respect between athletes, and unity.