Alexander the Less-than-Perfect: How Did the Great Alexander Die?

The cause of Alexander the Great’s death remains one of history’s great puzzles. Let’s take a look at the most popular theories.

On the 11th of June 323 BCE, in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon, Alexander the Great breathed his last. At just 32 years old he had carved out the largest empire that the world had yet seen, uniting Greece, Anatolia, the Levant, Egypt, and Mesopotamia under a single power and toppling the formidable Achaemenid Persian Empire. Alexander was treated like a god among men, but he was as mortal as anyone else. His sudden death left a vacuum and his empire was soon torn apart by the ambitious men who lay claim to his legacy.

The question of what killed Alexander has captivated historians for over two thousand years. What could possibly have brought down history’s greatest conqueror at such a young age? Historians and medical professionals have poured over the accounts of his final days and proposed several theories about what killed Alexander the Great.

Alexander the Great’s Death in the Sources

Dying, Alexander the Great bids farewell to his army, Carl von Piloty, 1885, via Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Alexander’s death occurred shortly after his return to Babylon following a difficult and ultimately unproductive campaign in India and only a few months after the similarly mysterious death of his close friend Hephaestion in 324 BCE. Several sources describe Alexander’s last days and agree on key details.

Plutarch’s account is the most detailed. In typical Plutarchian fashion, the event was preceded by omens — a flock of ravens falling dead at Alexander’s feet, a prized lion being kicked to death by a mule — that indicated the imminent death of the conqueror. Alexander recognized these portents and became even more paranoid in his last weeks. Eventually, Alexander was struck with a fever after a night of drinking that gradually worsened over the following days. Alexander retired to his bed and, over several days, lost the ability to move or speak. Ten days after the fever struck, he was declared dead. Apparently, the deified man’s body did not decay and remained pristine after his death.

The Death of Alexander the Great, Jean Restout, 1692-1768, via MutualArt,

Plutarch also presents several other accounts that add different details. For example, some sources claimed that Alexander suffered a sudden stabbing pain in his abdomen while drinking, and this signaled the beginning of the fever and his fatal illness. Plutarch also tells us that no one initially suspected poison, but such accusations gained steam some years after the king’s death.

Diodorus Siculus similarly shows Alexander being aware of his imminent death. Diodorus also places Alexander’s illness immediately after a night of hard drinking with his friends that was interrupted by a sudden abdominal pain. Alexander’s pain and fever worsened over several days until it was obvious, he would not survive. When asked to whom the empire should pass after his death, the ailing Alexander simply replied, “to the strongest.” Also, like Plutarch, Diodorus offers his readers alternate theories for Alexander’s death, namely that he was poisoned by his enemies within his court. The account of Quintus Curitus Rufus echoes Diodorus’, although Curtius is more amenable to the theories that poison was the true cause of Alexander’s end.

Although there are some disagreements, there are several details that are consistent across all or most accounts:

Fever that worsened over several days

Intense partying and alcohol consumption the night before the onset of the illness

Gradual decline in his ability to move or speak

Sudden intense abdominal pain at the start of the illness (not Plutarch)

No initial suspicion that Alexander had been poisoned

Absence of decomposition of the body after death

Scholars have used these details to construct several theories for Alexander’s death. We will proceed through the most popular theories and determine which one best aligns with the information in the sources.

Was Alexander Poisoned?

Alexander the Great Founding Alexandria, Placido Constanzi, 1736-7, via The Walters Art Museum

As we have seen, theories that Alexander was poisoned are thousands of years old. Any number of people could have had the motivation to eliminate the king: resentful subjects, spurned nobles, or ambitious rivals all had reasons to want the king dead.

First, we must determine whether poison fits the symptoms of Alexander’s fatal sickness. Given the sheer variety of deadly substances, it is easy to find several that might work. Scholars have suggested ergot, a fungus that grows on certain types of cereals and can produce symptoms of high fevers, coma, and death, as one potential poison, although it does not produce the same gradual decline in faculties observed in Alexander nor the intense abdominal pain.

Graham Phillips, in Alexander the Great: Murder in Babylon, suggested strychnine poisoning, a relatively rare poison in the ancient world that might easily have gone unnoticed and was easily masked when mixed in with wine. However, strychnine does not typically cause fever and instead produces convulsions that are wholly absent from accounts of Alexander’s death.

Helleborus Vesicarius, a variety of poisonous hellebore native to Anatolia and the Middle East, via Wikimedia Commons

Leo Schep proposed hellebore as the fatal culprit. This poisonous plant was well-known to the Greeks and would have been mixed with wine, which is consistent with accounts that place his sudden illness after a night of drunken revelry. Hellebore also produced a more protracted poisoning than other substances, complete with a high fever and abdominal pain, although the gradual loss of speech and motor functions described in Alexander’s death are not typical of this poison.

The trouble with diagnosing a poison is that different people can manifest different symptoms. It’s also possible that a concoction of multiple substances was used. Therefore, we cannot assert a single poison as the cause. However, every symptom of Alexander’s illness could have been caused by one poison or another, so we cannot discount the poison argument either.

Who Poisoned Alexander?

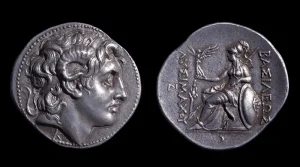

Alexander (obverse) and Athena (reverse), Silver tetradrachm issued under Lysimachus, 305-281 BCE, via The British Museum

The poison theory also depends on circumstantial evidence. Poison looks more likely when one considers how many people had the means or the motivation to eliminate Alexander.

The obvious candidate who is named in both Plutarch and Curtius is Antipater. Antipater was an elder statesman and general who was entrusted with the governance of Macedonia and Greece in Alexander’s absence. By controlling such an important part of the empire, and being an experienced and respected leader in his own right, Antipater was the second most powerful person in Alexander’s empire. Alexander’s paranoia was well-known — he had already eliminated another elder statesman Parmenion on specious pretenses a few years earlier — and Antipater would have recognized his precarious position. Furthermore, Antipater had two sons in close proximity to Alexander: Cassander and, crucially, Iolas, who served as Alexander’s personal cupbearer.

Diodorus, Curitus, and several modern scholars have proposed that Antipater ordered the poisoning of Alexander out of fear that Alexander would eliminate him in time. These fears were perhaps justified. Shortly before his death, Alexander had dispatched a small army to Greece under the command of Craterus, with most scholars agreeing that Craterus was sent to relieve Antipater of power. Before he could be removed, however, Antipater secretly sent orders to Iolas to poison the king. Being the cupbearer, it would have been an easy crime.

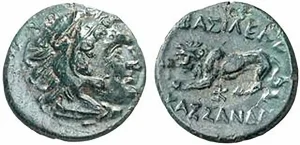

Stater coinage of Cassander, son of Antipater, produced during his rule of Macedon 305-297 BCE, via Wikimedia Commons

Later events lend some support to this theory. After Alexander’s death, Antipater did not willingly submit to the designated heir, Perdiccas, and led a coalition against him. After Perdiccas’ death in 321 BCE, Antipater was effectively the head of the empire until his own death a few years later.

Amid the chaotic wars of the successors, Antipater’s son Cassander showed an ambition for power and briefly ruled Macedonia himself. Cassander also ordered the execution of Alexander’s young son, Alexander IV, in 309 BCE, before the young heir could be old enough to inherit his father’s power. Plutarch reports that Cassander was deathly afraid of Alexander, even in death, and would panic when he merely saw a statue of the man. Was this fear one that masked guilt for his role in killing the great conqueror?

If not Cassander, then Iolas is another obvious culprit, and Alexander’s own mother agreed. Iolas died around 320 BCE, but after his death, Olympias accused Iolas of poisoning her son and had Iolas’ body exhumed and desecrated. This might have been a political move to target Antipater’s faction amidst the wars of the successors, or it could be a mother’s sincere belief in punishing the man who murdered her son.

Eumenes fighting Neoptolemus during the wars of the diadochi, a typical example of the internecine warfare in the wake of Alexander’s death, possibly by Heinrich Leutemann, 1878, via Wikimedia Commons

Antipater and his family are probably candidates, but far from the only ones. Perdiccas, who became Alexander’s actual successor, obviously profited from his death and would be a natural suspect. However, no sources accuse him of the crime, and none of his many enemies ever accuse him either. Another suspect was Alexander’s wife, Roxanne. Graham Phillips noted that the rare strychnine poison was native to her homeland of Bactria, and the young woman chose to dispose of the man who’d forced her into marriage and subjugated her kingdom. As with Perdiccas, there is no contemporary evidence of this, and is based purely on speculation.

Many other people could have been responsible. Any number of ambitious nobles in court could have killed Alexander, perhaps hoping to rise to the top in the inevitable scramble for succession. Members of the Persian elite could also have wanted to avenge their fallen empire by eliminating its destroyer. Even the Greeks resented Alexander’s dominance and launched a rebellion shortly after his death, adding to the already formidable list of suspects.

The truth is that we do not have the evidence to assert that Alexander was poisoned. It remains a tempting possibility, a favorite for historical fiction and sensational headlines, but just one theory among many.

Did He Drink Himself to Death?

Banquet of Alexander, engraving, Domenico del Barbiere and Francesco Primaticcio, 1540-50, Via Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Consistent among every account is that Alexander’s illness appeared during or shortly after a night of intense drinking with his friends. It is natural to ask whether alcohol had anything to do with his demise.

Alexander’s contemporaries would have been well aware of alcohol poisoning and its symptoms, but none of the sources suggest that is what killed him. The protracted nature of Alexander’s illness is also inconsistent with alcohol poisoning, as is the absence of vomiting, which is a distinct sign of alcohol poisoning.

It is possible that alcohol exacerbated, but was not the root cause, of an underlying illness. One theory is that Alexander was killed by acute necrotizing pancreatitis exacerbated by heavy alcohol consumption. This is when tissue from the pancreas starts to die and potentially causes a fatal septic infection in the bloodstream. Sudden intense abdominal pain is consistent with this diagnosis. The gradually escalating fever aligns with a worsening infection caused by the necrotizing organ. Late-stage infections can also cause the loss of speech and motor functions consistent with the accounts of Alexander’s death due to swelling of the brain.

This theory was first proposed by C. N. Sarbounis in 1997 and has enjoyed support from a number of other historians and medical professionals. There are no obvious incompatibilities with any of the accounts of Alexander’s death, but it would also be unreasonable to assert that such a rare ailment was definitely the cause of his death when other explanations are plausible too.

Did Alexander Die of Disease?

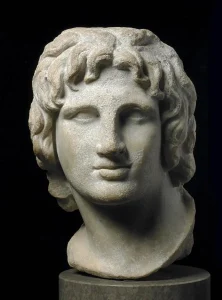

Marble head of Alexander the Great, 2nd-1st century BCE, via the British Museum

Other scholars have proposed infectious disease as the cause of Alexander’s untimely death. Stress from the recent Indian campaign, the loss of his Hephaestion, and the accumulated stress of years of military campaigns could have weakened Alexander’s immune system and made him vulnerable to any number of illnesses. Three candidates deserve special attention on this front.

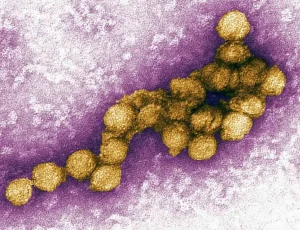

John Marr and Charles Calisher were the first to propose West Nile virus (WNV) as Alexander’s killer. They suggested that the omen of dying birds in Plutarch’s account was no fictional construct but evidence of the disease’s presence in Babylon at the time of Alexander’s death. Birds act as hosts for the WNV and, similar to how the mass death of rodents can anticipate an outbreak of Black Death, the mass death of birds preceded an outbreak of WNV in Babylon. Alexander could have been infected by a mosquito which picked up the disease from one of the birds, which resulted in his death.

Colorized transmission electron of micrograph (TEM) of West Nile virus, via Encyclopedia Britannica

Intriguing as this theory is, Alexander’s symptoms do not indicate WNV. Fever is the only significant symptom shared between a typical WNV infection and Alexander’s illness. Early WNV infections produce delirium and confusion that was not apparent in Alexander’s case, and paralysis or comes as seen in Alexander’s last days is extremely rare, even in fatal cases of WNV.

The other candidate is, of course, malaria. Arguably the biggest killer of human beings in history, malaria is almost always a reasonable suspect in any unexplained death in its endemic areas. Malaria was endemic to Mesopotamia. The Euphrates River that ran through Babylon, in which Alexander would have bathed countless times, must have been infested with these malaria-carrying insects. It’s also plausible that Alexander was infected at some point in his years-long conquest and faced a sudden fatal relapse at Babylon. Alexander’s worsening fever is a good fit for a malaria diagnosis. Severe cases of malaria can produce neurological conditions that fit Alexander’s loss of bodily functions and could have sent him into a coma before he died.

Both diseases would leave Alexander’s abdominal pain unexplained, however, and another candidate offers a stronger explanation that accounts for all symptoms: typhoid fever.

Typhoid fever is caused by a bacterial infection usually acquired from contaminated food or drinking water. It has been a common ailment throughout history and was almost ubiquitous around the world in the pre-industrial age. David Oldach was the first to argue that Alexander’s worsening fever with abdominal pain and eventual loss of key bodily functions, perhaps due to encephalitis, were indicative of a fatal typhoid infection. Oldach pointed out that serious typhoid infections can cause a ruptured bowel which could explain the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that our sources record. A counterargument for the typhoid diagnosis is that a perforated bowel typically occurs very late in the infection, not at the start.

Once again, we are left with many possibilities but no certainty. Typhoid fever appears more likely than WNV or malaria, but there is no smoking gun that definitively settles the question in favor of one infection or another.

Was He Even Dead at All?

Death of Alexander the Great, Nicola de Laurentiis, 1783-1832, via MutualArt

One final possibility should be discussed, and it is by far the most disturbing: it is possible that Alexander was not dead at all.

Of course, Alexander did die in 323 BCE, but he might not have died when people thought he did. Katherine Hall suggested that Alexander was afflicted with Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS). GBS is a condition where the immune system attacks the nervous system causing severe neurological damage, including difficulty speaking, paralysis, and eventually death. GBS can occur due to a number of infections, including both typhoid fever and acute necrotizing pancreatitis, which were discussed earlier.

The true horror of a GBS diagnosis hinges on that last consistent detail of Alexander’s death: his body did not decompose after death. In the ancient world, death was determined based on breathing, not pulse. Hall suggested that GBS caused near-total paralysis that made Alexander’s breathing imperceptible but that he was very much alive and possibly still conscious. The reason Alexander didn’t decompose was that he wasn’t dead. This theory presents a vision of Alexander, unable to move or speak, trapped in his own mind in his last days while everyone around him treated him as a corpse.

Hall concludes that Alexander was the most famous case of “pseudo-Thanatos” or false diagnosis of death in history. Of course, Alexander did eventually die. Lack of food or water would have seen to that, even if the infection didn’t, but for hours or even days, it’s possible that Alexander lay there unable to tell anyone that he was still alive.

Verdict: How Did Alexander the Great Die?

The Alexander Sarcophagus, depicting scenes of Alexander’s conquests and thought to belong to Abdalonymus, King of Sidon, 4th Century BCE, via Wikimedia Commons

As with so many historical mysteries, we have to choose between several plausible options and accept that we cannot offer a definitive answer.

In their review of the historiography of Alexander’s death, Mishra et al. concluded that acute necrotizing pancreatitis was the ultimate cause of Alexander’s death. Excessive alcohol consumption exacerbated the necrotizing process, which in turn led to a serious infection that spread into the bloodstream. This infection could have led to brain swelling, which explains the neurological decay in Alexander’s last days, or caused GBS as his body’s immune system tried and failed to repel the infection. The symptoms of GBS led to a mistaken diagnosis of death while Alexander was still alive and created the legend of his non-decomposing body.

This diagnosis accounts for all of the peculiarities of Alexander’s death and aligns with modern observations on these illnesses that were beyond the knowledge of Alexander’s contemporaries. It is not a definitive diagnosis, and plenty of reasonable doubt exists. However, on the strength of the evidence, acute necrotizing pancreatitis leading to GBS is the strongest theory for how history’s greatest conqueror met his untimely end.