Macedonian King Philip II: The Man Who Made Alexander “Great”

Alexander the Great’s achievements rested on those of his father. Who was Philip II of Macedon and how did he enable his son’s “greatness”?

In his day, Philip II was arguably the most significant player in the politics of the Eastern Mediterranean. He was a wise innovator, a masterful tactician, and a shrewd diplomat, who carried Macedon from the periphery to the apex of Mediterranean power politics.

However, his life is usually overshadowed by that of his son, Alexander the Great. Often, he appears in the historical record only as a prelude or side character in his son’s path to glory, but Philip was a fascinating individual who deserves his own share of attention.

Early Life

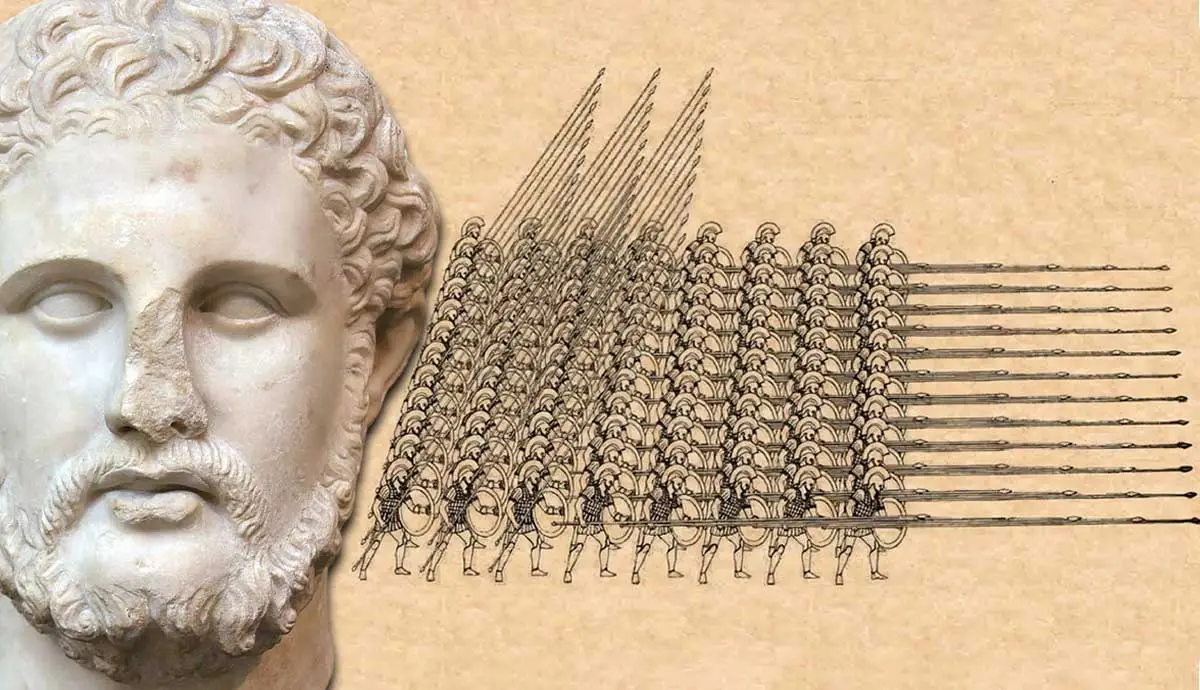

Bust of Philip II, Roman copy of Greek original, by Roger Mortel, Source: Wikimedia Commons

Like many great rulers, Philip was never meant to be King. Born around 382 BCE, he was only the third eldest son of King Amyntas III of Macedon, and his elder brother Alexander II was destined to succeed his father. However, after Alexander’s assassination by a powerful courtier, the young Philip was sent away as a diplomatic hostage, first to the Kingdom of Illyria on the coast of the Adriatic Sea, but then to Thebes. In Thebes, he learned at the feet of the legendary Theban General Epaminondas, and the lessons Philip learned there would reshape Greece, Macedon, and the world forever.

Philip returned to Macedon when he reached adulthood. His second-eldest brother Perdiccas III trusted Philip and appointed him as regent for his own son Amyntas while the King was out on campaign. However, in 359 BCE, King Perdiccas was killed in battle against the Illyrian ruler Bardylis. Philip became the regent for his infant nephew but quietly sidelined Amyntas to establish his own power. He was kind enough not to kill Amyntas and permitted him a life of relative comfort, but he never allowed his nephew anything that might challenge his own power.

Philip the Innovator

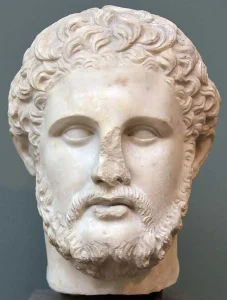

The Macedonian Phalanx, Source: Hellenic-art.com

Philip’s time under Epaminondas honed his military skill and he embarked on a series of tactical and military reforms as king that paved the way for Macedon’s future glory. The most important was the introduction of the sarissa. The sarissa was a long spear roughly twice the length of the traditional dory used in Greek and Macedonian warfare.

Warfare in this period was based around phalanx formations — men armed with spears and shields in a tight formation, providing an unbreakable wall of protective shields and offensive spears. The Greeks had perfected this type of warfare and famously employed it in battles such as Thermopylae and Marathon.

Philip’s sarissa was a simple change, but a profound one. By doubling the length of the spear, he doubled the distance between his own men and the enemy’s weapons. Furthermore, because the spears were so long, additional rows of phalangites could point their spears in front of the formation, creating multiple layers of spears for attackers to get through. This made the Macedonian phalanx almost impenetrable.

Philip also improved the use of cavalry by forming the hetairoi, or Companion Cavalry. This elite heavy cavalry force was comprised of the Macedonian elites and were typically personally led into battle by the king. Usually, the sarissa-equipped phalanx units would hold an enemy in place while the swift hetairoi outflanked the enemy. This combination would be devastatingly effective against the Persians.

Lastly, Philip innovated with the use of siege equipment. He made one of history’s first use of catapults against the town of Byzantion in 340 BCE and made liberal use of siege towers, battering rams, and early ballistae named oxybeles. Although he had mixed success with them, his varied and sophisticated array of siegecraft equipment would be indispensable to Alexander’s later conquests.

Early Campaigns

Statue of Olympias and Alexander the Great, by Wilhelm Beyer, 1779, Source: Schönbrunn Palace

Upon seizing power, Philip’s immediate political concerns were the Illyrians. Having killed his predecessor in battle, the Illyrians posed a unique threat as they had been emboldened by their success and might inspire others to revolt against Macedonian power. Philip marched to meet the Illyrians in the Erigon Valley in 358 BCE, where he decisively defeated them and slew their king on the field.

On top of his military acumen, Philip understood the value of marriage as a political tool. He secured the obedience of Illyria through marriage to the Princess Audata and consolidated his control of Elimeia by similarly marrying Phila of Elimeia. By far his most consequential union came from Princess Olympias of Epirus in 357 BCE. By all accounts, Olympias was a formidable and wilful woman, and together they quickly conceived a son, whom they would name Alexander.

Philip in Greece

Macedonian Coin, head of Zeus with Philip II on horseback, 340-315 BCE, Source: The British Museum

Philip continued his expansion by acquiring the gold-rich territory around the city of Amphipolis in 357 BCE and that same year he conquered the city of Pydna. These actions directly defied the demands of Athens and brought Philip fully into the shifting alliances of the Greek world.

The dispute over Amphipolis and Pydna led to ten years of intermittent conflict between Philip and Athens. Philip continued to prove himself an able battlefield commander. He wrested multiple cities out of Athenian control with remarkable success, although the city of Methone did cost him his right eye. He then carried his campaigns into Thrace and Thessaly, further expanding Macedonian power at the expense of the Greek city-states.

From 356 BCE, Philip was dragged into the Third Sacred War as an ally of Thebes against the Phocians. Despite initial successes, Philip was actually defeated in battle by the Phocians but dusted himself off and redoubled his efforts. He delivered a decisive revenge upon them at the Battle of Crocus Field in late 353 or early 352 BCE where he killed or captured almost 10,000 Phocians. The victory rewarded Philip with effective control of Thessaly and a powerful stake in Greek affairs that he would only expand.

Raising Alexander

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), taming Bucephalus, by Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1826/7, Philip is seated on the right, Source: The National Trust Collections

Amid his military and diplomatic achievements, Philip still found time to be present in his son’s life.

Philip features in several famous anecdotes from Alexander’s early life, although not all of them may be true. For example, it was Philip who tried and failed to tame the horse Bucephalus before Alexander managed to subdue the beast and make him his loyal companion. Philip supposedly wept with joy and told his son to find a bigger kingdom because “Macedon is too small for you.” An unintentionally prophetic prediction for a future conqueror, or a later invention to bolster the heroic destiny in Alexander’s myth? The latter is more likely.

For his part, Philip appears to have trusted Alexander. In one Plutarchian tale, Alexander was trusted to receive Persian ambassadors while Philip was away from court. In another, he entrusted the 16 year old Alexander with the regency while he was on campaign, during which the young Alexander successfully subdued a rebellion in Macedonian territory.

Many of these anecdotes are dubious, but we do know that Philip made some impressive provisions for his son. Most famously, Philip arranged for Aristotle to personally tutor Alexander. Teacher and student enjoyed a close relationship for many years and one can think of few people in history who might be as impressive a teacher for a young man to have. Clearly, Philip wanted Alexander to have the best education possible.

Philip Grows His Kingdom

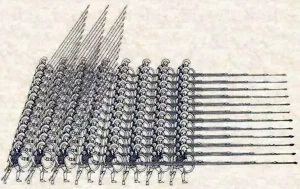

Roman-era bust of Demosthenes, photo by Eric Gaba, 2005, Source: Wikimedia Commons

If Macedon really was too small for Alexander, then Philip was doing an excellent job in expanding it for him. From the late 350s to 340s BCE, Philip engaged in a string of campaigns to expand his borders. Philip secured Macedonian dominance over Balkan hill tribes to the north and east of Thrace. He also tightened his control over Epirus and Illyria in a series of short punitive campaigns after they had become restless while Philip had been focused on Greece. By 342 BCE, he had effectively doubled the size of his kingdom and held it more firmly than ever before.

Meanwhile, in Greece, he turned to diplomatic means to slowly increase his power. He compelled Athens to accept peace in 346 BCE and his decisive role in Greek affairs earned him membership of the Amphictyonic League, signaling his important place in the region.

This dominance did not go unnoticed, least of all by Athens. Despite the peace they’d signed, Athens continued to work against Philip and feared his growing power. The famous statesman and orator Demosthenes delivered five fiery speeches, all of which have survived, condemning Philip as a tyrant who would destroy Greece if given the chance. The Athenians even sent an embassy to Persia asking for support in a war against Philip but they were denied. Soon though, Athens would come to regret its hostility to Philip and their hopes of seeing him fall would come crashing down.

Philip Subdues Greece

Thebans and Macedonians at Chaeronea, by Edmund Ollier, 1882, Source: Cassell’s Illustrated Universal History, online at The Internet Archive

In 340 BCE, Philip attempted to besiege the city of Byzantion. This posed a direct threat to Athens’ grain imports from the Black Sea, prompting them to send ships and supplies to repel Philip’s attack. Despite employing his powerful catapults in the siege, the Athenian intervention ultimately forced Philip to withdraw. Their short-lived peace had shattered and Philip’s retreat emboldened the Greeks who shared Athens’ anxiety over Macedon’s newfound power.

After Philip licked his wounds and reorganized, he marched back into Greece the following year. By this point, even his former Theban allies were unhappy with his dominance and would stand with Athens and several other cities to try to put an end to Philip’s power once and for all.

The Battle of Chaeronea in August 338 BCE ended Greek hopes of independence. Philip’s forces decisively defeated the Athenian and Theban-led coalition assembled against him. Details of the battle are scarce, but we know that Alexander himself rode in the Companion Cavalry alongside his father.

Chaeronea was a decisive moment. It established Macedonian dominance over most of Greece and Greece would spend most of the next 2,000 years under the influence of foreign hegemons or imperial powers like those of Macedon.

Philip secured his power using a confederation known by historians as the League of Corinth. This League imposed a political order upon the various city-states, including a mutual peace, with Philip firmly as its hegemon. It was the first time that all of Greece — save initially for Sparta, who only joined under Alexander — was unified into one political order. Macedon itself was not represented in the League and Greek cities were free to dispute among themselves on many issues, which preserved some sense of independence for them, but Philip’s hegemonic role allowed him to rise above those disputes and, crucially, direct the League’s anger (and military resources) against something far more productive: Persia.

Eyeing Up Persia

Map of Philip’s Empire and Persia at the time of his death, 2009, Source: Wikimedia Commons

The massive Eastern empire had endured a series of rebellions and regime changes in recent years, and this combination of vulnerability and lavish wealth made for a tempting target. Additionally, the Greeks were still animated by anti-Persian hatred due to their invasion in the 5th century BCE. Using his newfound position in the League of Corinth, Philip could muster the combined military might of Greece to strike out at their ancient enemy.

It was actually Philip, not Alexander, who sent the first troops eastward into Persia. A preliminary force of several thousand men was sent ahead under the command of Parmenion and had begun to wrest control of several Greek cities in Asia by the end of Philip’s life.

In anticipation of this invasion, Philip sought another marriage with a Macedonian woman named Cleopatra to secure an additional heir in case Alexander died on the campaign. It was a sound move, but for Alexander, it was a wound to his pride, a sign that his father possibly wanted to replace him. After all, Alexander’s mother was from Epirus, so a son from this marriage would technically have a more legitimate Macedonian claim.

According to Plutarch, an argument broke out about this during the wedding in 337 BCE which led to Alexander openly mocking his father. The resulting rift in the family made Olympias and Alexander enter voluntary exile in her homeland of Epirus for several months, but Alexander was later recalled as the time for the Persian expedition drew near — an expedition that Philip would never see.

The Assassination of Philip

Depiction of Assassination of Philip II of Macedon, Source: The Story of the Greatest Nations, from the Dawn of History to the Twentieth Century, by Edward Sylvester Ellis and Charles Francis Horne, 1900, online at The Internet Archive

In October 336 BCE, Philip celebrated the marriage of one of his daughters in the city of Aegae. While entering an amphitheater, one of his bodyguards, a man named Pausanias, suddenly stabbed him with a dagger. Philip fell and quickly died, ending the life of one of the ancient world’s greatest military minds.

Pausanias was quickly killed by Philip’s soldiers and Alexander was enthroned as Philip’s successor.

Our sources disagree on the motive for the attack and who was involved. The simple explanation by Diodorus Siculus is that Pausanias was a spurned lover who killed Philip in a fit of jealousy and rage. In his Politics, Aristotle instead blames a dispute between Pausanias and another Macedonian courtier that Philip failed to resolve in his would-be assassin’s favor.

Others point the finger at Olympias and Alexander. Plutarch says that it was Olympias who fanned the flames of Pausanias’ anger and made him strike down the king. The fact that she was still in exile in Epirus gave her plenty of motive to hate Philip and seek to hasten her son’s rise. Plutarch and Justin both implicate Alexander, although always at arm’s length — he did not plan or order the assassination, but he might have known of the plan and chosen not to stop it.

Modern analyses have failed to settle the debate. Some historians note that Alexander gained nothing from the assassination that he wouldn’t have received by simply waiting, but then again, Alexander was not a man renowned for his patience. While there’s no actual evidence linking Alexander to the crime, that has not stopped over 2,000 years of speculation that Alexander earned his throne by murdering the man who raised him.

A Legacy for the Ages

Entrance to the Tomb of Philip II, Vergina, Greece, photo by Sarah Murray, Source: Wikimedia Commons

Whatever or whoever motivated Pausanias to kill Philip, we will probably never know. After his assassination, Philip was interred in a marvelous tomb in the city of Aigai, modern-day Vergina in Greece, which archaeologists discovered untouched in 1977. Newspapers ran headlines celebrating the discovery of the tomb of “Alexander’s father,” a man whose modern relevance is almost always bound up with that of his son.

Philip achieved much in his own right. He took the peripheral kingdom of Macedon and turned it into the hegemon of Greece and one of the greatest powers in the Mediterranean. It was Philip who introduced the sarissa that revolutionized warfare for centuries to come, who formulated the League of Corinth, who had first appointed men like Parmenion to positions of power, and it was Philip who had conceived of the Persian campaign in the first place.

Alexander may have built the empire, and he deserves his credit for doing so, but the foundations he stood upon and even the tools he used had been crafted for him by Philip. While he might not be as well remembered as his son, Philip’s achievements echo throughout history all the same.