A Synopsis of Classical Greek Theater: A Peep into the Past

From Shakespeare to Broadway, modern theatrical performances owe much of their success to the innovation of Ancient Greek drama.

Mosaic depicting theatrical masks of Tragedy and Comedy, 2nd century CE, at Capitoline Museums, via Flickr/Carole Raddato

From the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides to the comedies of Aristophanes, Ancient Greek theater was part of a culture of performance among the Greek city-states. Performance, extending to military excellence, public speaking, and theatrical performances, was an integral part of life for the average Athenian citizen. Theater, deriving from the Greek word “theomai” (to see), was not just an important past-time in the ancient world; it also was a form of art that greatly influenced modern theater.

The Genres of Ancient Greek Theater

Tragedy

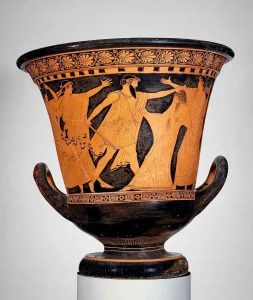

Mixing bowl (calyx krater) with the killing of Agamemnon, artist unknown, 460 BCE, via Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Greek theater was primarily divided into two distinct genres that complimented one another: tragedy and comedy. Greek tragedy, or tragoidia, is the genre to which most surviving Greek theater works belong. This genre centers around human suffering, usually involving a figure falling from prosperity into despair. The structure of tragedies is relatively consistent among the popular Athenian playwrights, beginning with a prologue (opening speech) that transitions into a parodos (the entry of characters). The parodos is followed by a series of episodes (dialogue between characters), which ends with an exodus (the exit of characters). Throughout the dialogue exchanges, the chorus interjects with a series of songs that comment on the events of the play.

Theatre Mask, artist unknown, 2nd-1st century BCE, via The British Museum, London

The cast of Greek tragedies was relatively small. Four actors rotated between roles, so there could never be more than four people on stage at one time (not including the chorus, which comprised at least 12 people). Instead of makeup or costumes, actors would wear different masks that represent their roles (see Theatre Mask image above). These “smiling” masks, which, in reality, had openings around the mouth for the actor to sing, have now become popular symbols of theater.

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask), by the painter of the Yale Lekythos, 470-460 BCE, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Out of the surviving completed tragedies, all were written by three playwrights: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Some popular examples that have even been part of high school English curriculums include Antigone, Oedipus Rex (or Oedipus the King), and Medea. One similarity between almost all surviving tragedies is that they center on human suffering in a mythological context. For example, the image above is of a terracotta vase that possibly depicts a scene from Seven Against Thebes, a tragedy by Aeschylus that is based on seven mythological warriors.

Comedy

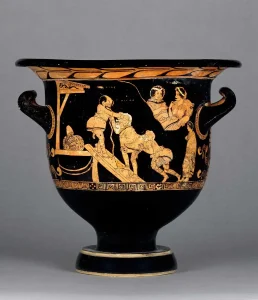

Bell krater, artist unknown, 380-370 BCE, via The British Museum, London

Comedy (from komoidia) began its development around a century after the tragedy, but that does not negate the lasting impact this genre had on ancient theater. Athenian comedy shared many traits with modern performances in the same genre, such as crude humor and political/societal commentary. Because of the range of comedy across different playwrights, this genre is also divided into three eras: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy.

Our modern understanding of Old Comedy is entirely characterized by the plays of Aristophanes from the 5th century BCE as the works of other playwrights from this era have not been preserved. Old Comedy is known for its satirical accounts of public figures and events that often criticize the social scene of 5th-century Athens. The three eras of comedy come and go quickly, as the transition to Middle Comedy happens at the end of Aristophanes’ life. Like Old Comedy, Middle Comedy focuses on social commentary, but playwrights’ criticisms became more general and societal rather than personal. Finally, the third phase of comedy is New Comedy, which rose to prominence in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. New Comedy parodies everyday life and domestic events rather than societal structures and politicians, essentially becoming humor for the average person.

Playwrights

Although hundreds, or even thousands, of playwrights produced works in Athens, very few of these plays have survived for modern audiences to enjoy. The most famous tragedies and comedies that are still read and performed almost all originate from the same four authors: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides for tragedy and Aristophanes for comedy. Despite the small sample size of works that have been preserved, these playwrights significantly impacted both the ancient and modern worlds with their writing.

Aeschylus

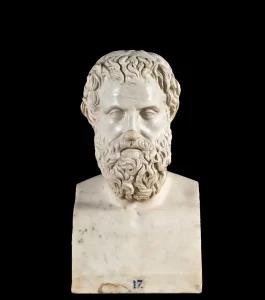

Aeschylus o Aeschines, artist unknown, 18th century, via Museo del Prado, Madrid

Aeschylus, the first of the three tragedians with surviving works, was born around 525/4 BCE at Eleusis (the polis where the Eleusinian Mysteries took place). Like many Greek men, Aeschylus served in the military and fought in the Greco-Persian Wars. His experience in the military possibly served as inspiration for the Persians, which was a tragedy centered on the aftermath of the Battle of Salamis. Out of the three tragedians, Aeschylus is viewed as being the most traditional, both by modern scholars and figures in the ancient world like Aristotle. His surviving works are the basis for many studies on the structure of tragedy, and he popularized certain elements of the genre (such as adding another actor to increase artistic freedom).

Some of Aeschylus’ notable works include the Oresteia trilogy (Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides) and Prometheus Bound.

Sophocles

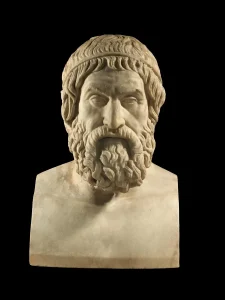

Marble head state of Sophocles, artist unknown, Roman period, via The British Museum, London

Sophocles, born around the second half of Aeschylus’ life in 497/6 BCE in Colonus, was the most popular of the tragic playwrights in Athens. During the City Dionysia, Sophocles won or placed high a majority of the years that he entered, surpassing both Aeschylus and Euripides. He lived through both the Greco-Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, and he took an active role in Athenian politics. Sophocles is often credited for major changes to the structure of tragic plays, such as adding a third actor (which becomes the standard in Euripides’ era).

Sophocles has seven surviving works that include Ajax, Electra, Antigone, Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonus, Women of Trachis, and Philoctetes.

Euripides

Portrait of Euripides, artist unknown, 1st century AD, via Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

The final tragedian with surviving extant works is Euripides, the youngest of the three. He was born in Athens in 484 BCE, and the majority of the surviving tragic plays belong to him. Although he has gained popularity from modern readers of his works, Euripides was not as well-received in his lifetime. He only won a handful of competitions at the City Dionysia, and his plays were controversial as they represented ideas of a new generation that differed from Aeschylus and Sophocles (or at least Aristotle argued this angle). Euripides lived through the aftermath of the Greco-Persian Wars, the Peloponnesian Wars, and the inner turmoil within Athens, so his works were shaped by the time he lived in.

Euripides has many popular plays that are still reperformed and discussed, including Medea, Electra, Bacchae, Hippolytus, and Alcestis.

Aristophanes

Aristophanes book illustration by Georg Adam, 1800, via The British Museum, London

Aristophanes, born in Athens in 446 BCE, is one of the few Greek comedy writers with surviving works. Although comedy did not receive the same cultural attention as tragedy, Aristophanes was a very well-known playwright in the 5th century, although not always for positive reasons. His plays relied on criticizing prominent figures in Athenian society who were often in the audience for these performances, meaning that he may have made a few enemies during his lifetime. Aristophanes’ works are used as a basis when discussing genre elements of Old Comedy, but some of his later works are also classified as Middle Comedy, making him one of the most influential ancient comic writers that is still analyzed by modern scholars.

Aristophanes has eleven surviving works, with a few examples being The Clouds, The Birds, The Frogs, Lysistrata, and The Women at the Thesmophoria Festival.

Festivals of Ancient Greek Theater

City Dionysia

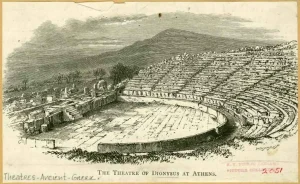

The Theatre of Dionysus at Athens by Edward Whymper, 1890, via the New York Public Library, New York

The City Dionysia was a pan-Athenian festival held each year in March in honor of the god Dionysus. The festival began with a procession to the Theatre of Dionysus on the south slope of the Acropolis, and the individuals in the procession carried a statue of Dionysus. The core of the festival centered around dramatic performances to honor the god associated with theater and revelry, and this event was one of the largest gatherings in Athens after the Panathenaea (a festival in honor of Athena). There is no record of the first City Dionysia, but it is known that only tragedy was performed at the festival until the early 5th century BCE when comedies began to appear in the awards list.

As a polis-wide event, the City Dionysia required months of preparation and large amounts of funding. It was common for prominent politicians in Athens to sponsor the festival or specific playwrights, sometimes giving them a special place in the festivities but also improving their reputation throughout the city. Politicians that sponsored playwrights would pay the actors and production fees, but the playwright sometimes had to cater their writing to their sponsor. For example, Aeschylus’ Persians was sponsored by Pericles, a politician who favored promoting the win at Salamis over other battles in the Greco-Persian Wars, thereby possibly influencing Aeschylus’ decision to base the tragedy around the Battle of Salamis.

In addition to the preparation required from sponsors and playwrights, actors and chorus members would train prior to performances each year. Acting was not a full-time occupation in Athens, but actors would be paid for their performances at the City Dionysia. On the other hand, the chorus was composed entirely of average citizens. The chorus typically consisted of 10-12 people, but this number could be much larger depending on the play. They were responsible for singing and dancing between dialogue exchanges, and this role was unpaid. Most male Athenian citizens would have been part of a chorus at least once in their life and often multiple times. Like most events in Ancient Greece, women were not permitted to perform in or even possibly attend the City Dionysia.

Lenaia

Terracotta roundels with theatrical masks attached, 1st century BCE, via The Met Museum, New York

Although the City Dionysia was the largest dramatic festival, there were other minor Athenian festivals held throughout the year. The most notable of these festivals was the Lenaia, an annual Athenian dramatic festival that took place each January. The Lenaia also honored Dionysus, but it was smaller in scale and had fewer performances than the City Dionysia. Originally, the Lenaia was a festival that only had works from comic playwrights, and it was where much of Aristophanes’ work was performed. However, it eventually introduced tragic performances in the late 5th century BCE. Women were more likely to have had a role in the Lenaia than the City Dionysia, but much is still unknown about their attendance and participation.