Rome vs the Macedonian Phalanx in the Macedonian Wars

In a series of conflicts known as the Macedonian Wars, the Roman Republic overcame the Macedonians and established Roman control of the east.

Contemporary but less famous than the Punic Wars, Rome’s Macedonian Wars helped transform the city-state into the first pan-Mediterranean power. In contrast to the drama of the Punic Wars, which saw the Romans pushed to the edge, the defeat of Macedonia seemed a simpler affair. But the descendants of Alexander the Great fought hard, to defend their power and their country, and showed a remarkable ability to recover from defeats and take a stand again against the seemingly irresistible rise of Rome.

It took four conflicts between 215 BCE and 148 BCE for the Romans to transform the ancient monarchy into a new province.

The First Macedonian War, 215-205BCE

The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus, 1789, Carle Vernet. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The First Macedonian War was a sideshow to the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) which brought Hannibal to the gates of Rome. This war without major battles often appears as little more than a footnote to the great events underway in Italy but it brought the Romans into the affairs of Greece and the Aegean.

When news of Hannibal’s great victories spread to Macedonia Philip V (221-179 BCE) made an alliance with the Carthaginian in 215 BCE. It has been argued that this aimed, not at an invasion of Italy as the Romans claimed, but at pushing back the recent Roman presence in Illyria (roughly modern Albania) on Macedonia’s border. While the Romans were more concerned with defending Italy than Illyria they could not risk Macedonia aiding Hannibal in any way and so they aimed at making Philip fight his war on his side of the sea.

The aims of the adversaries dictated the course of the war. With few resources to spare the Romans did not send any large armies across the sea and instead relied on their fleet and local allies to keep Philip busy. The Macedonians struck at the Roman-controlled cities along the Adriatic coast and eventually made headway after a poor start and captured the city of Lissus in 213 BCE. An invasion of Italy though was out of the question as Philip’s fleet was incapable of challenging Roman control of the sea.

Tetradracham of Philip V. Source: the American Numismatic Society

This command of the sea allowed the Romans to find allies to continue the war in the absence of significant Roman resources. The most important of these were the Aitolians, a federal league in central Greece that had frequently fought the Macedonians. To the south, the Spartans joined the war on the Roman side due to their long-standing rivalry with Philip’s ally, the Achaian federal state. Across the Aegean, the kingdom of Pergamon, fearful of a powerful Macedonia, sided with Rome. These alliances brought Rome even further into Greek politics.

This was not enough, though, to stop the war from developing into a stalemate. The Roman fleet and its allies kept Philip busy fighting in central and southern Greece but could not threaten Macedonian power nor Macedonia itself. If Philip ever had ambitions of crossing the sea, his inability to capture the whole Illyrian coast and the need to fight on several fronts stymied them. Gradually the war petered out. Pergamon withdrew to defend its heartland in Asia Minor. The Aitolians made a separate peace in 206 BCE and Philip and the Romans agreed to the peace of Phoenice the following year.

Under the terms of the peace, Philip kept some of the newly captured territory in Illyria. This and his defense of key Macedonian-controlled land and allies probably made the outcome satisfactory. The Romans too had achieved their aims. With minimal resources, they had kept a Carthaginian ally out of the war in Italy long enough for it to be won. However, this drawn conflict solved nothing in the long term.

The Second Macedonian War, 200-196BCE

Roman Republican solider, 2nd century BCE: Source: Louvre

War resumed barely five years after the end of the first conflict. Freed from the Second Punic War the Romans were no longer distracted and for the first time could seriously confront Philip.

Following the first war, Philip sought to gain new territories east of Macedonia, bringing him into conflict with Pergamon and the Rhodians. These two, along with Athens, which had its own dispute, called on the emerging power in the region, Rome. The aristocratic Senate managed to overcome a certain amount of war weariness amongst the Romans and by 200 BCE the Roman fleet was again on the offensive as Rome, Pergamon, the Aitolians, Rhodians, and Athenians went to war with Philip.

The Macedonian phalanx, via Livius.org

The war started slowly for this Roman alliance. A number of brutal Roman attacks on cities allied with Philip earned them a reputation for barbarism, while attempts to invade Macedonia made little progress. The war turned in Rome’s favor with the arrival of a new commander in 198 BCE, Titus Quinctius Flamininus. Young, ambitious, and a fluent Greek speaker Flamininus was a wise choice on both the military and political levels of the war.

Quickly the war started to go against Philip. The Achaians, a key Macedonian ally, defected to Rome, threatening Macedonia’s long presence in Greece. Thessaly, just south of Macedonia, was invaded. Philip tried to block the Roman advance at the gorges of the river Aous, but Flamininus got around his position and inflicted a significant defeat. Though Philip had lost allies and soldiers in the recent battle, his main army of more than 25,000 men remained intact. When a round of peace talks collapsed, this army was now Philip’s best chance to settle the war.

At Cynoscephalae in Thessaly, two of the ancient world’s most famous military units, the Macedonian Phalanx and the Roman Legion, confronted each other. This clash would be the first major battle after two decades of intermittent conflict. Flamininus invaded Thessaly in early summer 197 BCE and both armies moved around the plains searching for supplies and each other until they collided at the battle at Cynoscephalae.

Map of the 2nd Macedonian War. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The collision of the two armies was a surprise, one that benefited the Romans. Flamininus and Philip now drew up their roughly similar-sized armies. Philip likely had around 25,000 soldiers to the 30,000 under Flamininus. Coming down from the top of the Cynoscephalae hills, Philip initially pushed the Romans back, but the other half of his army was attacked and quickly overwhelmed. At this critical moment, the difference between the Roman and Macedonian armies told. In the absence of the king, one half of the Macedonia army was defeated while the other half could only continue to advance. Out of the Roman army, one unnamed officer was able to seize the initiative and broke away with a small group of soldiers from the advancing Roman right to attack the undefended flank and rear of the phalanx. Unable to turn and face this new threat Philip’s army broke. 8,000 were killed and 5,000 captured for the loss of around 700 Romans (Polybius.18.27). The flexibility of the Roman legion had triumphed.

In the aftermath, Philip was forced into a new peace with Rome. He was able to keep his throne, and there was no Roman occupation of Macedonian, but the king’s power beyond his borders was broken. Flamininus declared the Greek cities free of their long submission to Macedonia.

The Third Macedonian War, 171-168BCE

Stater of Flamininus, 196BCE. Source: The British Museum

After Cynoscephalae, Macedonia was reduced to its own borders, but within those borders, Philip V continued to reign, and over the next two decades, he and his son Perseus (179-168BCE) rebuilt their army and their kingdom.

The image we get from our Roman or largely pro-Roman sources is one of continual Roman distrust of the Macedonian monarchy. Philip and Perseus did not follow an aggressive foreign policy, and they often bowed to Roman demands, but the careful rebuilding of their army led to suspicion. By the late 170s, the Roman senate was willing to listen to complaints against Perseus from Greek allies, and by 171 BCE, Roman legions were again on their way to Macedonia.

The war did not start badly for Perseus. 171B CE brought a minor Macedonian victory at the battle of Callinicus. The following year Perseus raided the Roman naval base at Oreus on Euboia and thwarted invasions of Macedonia. The Romans improved their position in 169 BCE and managed to get over the passes of Mt Olympus and into Macedonia itself before progress stalled. It took the arrival of a new veteran commander, Lucius Ameilius Paullus, to change the situation.

As 168 BCE opened, Paullus and Perseus faced each other in southern Macedonia with roughly equal forces of around 39-40,000. Perseus took up a strong defensive position with a river between himself and the Romans. Perseus feared the Romans getting around his defenses by the sea. In the end, they did so by land. When a Roman force suddenly descended from the mountains behind Perseus, he was forced to retreat towards the town of Pydna.

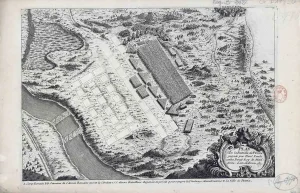

Plan of the battle of Pydna, 18th century. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

By late June, the two armies met somewhere near Pydna, but the confrontation that would be remembered as the battle of Pyda that developed on 22nd June started accidentally. A skirmish developed in the afternoon as scouts from both sides clashed over a breakaway horse. This skirmish gradually drew in more and more troops until a general battle unfolded. Once the legion and phalanx clashed, the battle was quickly over. The flexibility of the legion again gave it the advantage as Roman soldiers advanced into the gaps in the Macedonian phalanx. With its unity broken, the phalanx quickly disintegrated, and the Romans massacred the defenseless army killing perhaps as many as 20,000 (Livy,44.42).

Perseus was soon cornered on the island of Samothrace and surrendered to Paullus. This time the Romans did not leave Macedonia intact. Perseus was shipped off to adorn Paullus’ triumph, and the now kingless Macedonia was broken up into four separate states. This seemed to be the end of Macedonia.

The Fourth Macedonian War, 150-148BCE

Silver coin of Perseus. Source: British Museum

Almost two decades after the disaster at Pydna, a brief Macedonian revival came from an unexpected source. In the late 150s BCE, a man named Andriscus, believed to be from Aeolis in Asia Minor, emerged, claiming to be an illegitimate son of Perseus. A circuitous route took him from the Seleucid court in Syria, via arrest in Italy, to Thrace on the borders of Macedonia, where he was proclaimed Philip VI.

The Romans underestimated Andriscus and were again distracted by the war against Carthage. The separate states Macedonia was divided into were unable, or unwilling, to defeat this new king and by 149 BCE Andriscus was ruling a reunited Macedonia. The first Roman force of just one legion was defeated and its commander was killed. The following year a larger force of two legions arrived under Quintus Caecilius Metallus. This army quickly forced its way into Macedonia and crushed Andriscus’ army at a second battle of Pydna. Though he fled back toward the Thracians who had previously supported him, Andriscus was beaten again and handed over to the Romans. This was the last mention of him in the historical record.

With this rebellion crushed, the Romans did not risk leaving the Macedonians to rule themselves again, and Macedonia finally became a Roman province. The crushing of Rome’s former ally, the Achaians, immediately after meant that by the end of the Macedonian wars, the conquest of the Macedonians and Greeks was complete.

The Rise of Rome and the Fall of Macedonia

The monument of Aemilius Paullus, Delphi. Source: The Pausanias Project

The fall of Macedonia was not preceded by a decline. Since the mid-fourth century, Macedonia had been a wealthy and well-organized kingdom with a powerful army. This was enough to dominate Greece and launch the conquest of the Persian Empire. Philip V and Perseus had their faults but they were competent kings and leaders. The wars with Rome were close contests, and it is possible that both decisive battles, Cynoscephalae and Pydna, could have gone differently.

They did not for several reasons. First, by the late third century, Rome’s control of Italy was more complete and effective than Macedonia’s rule of Greece. Hannibal was in Italy for several years and won over some states but never broke Roman control. In contrast, various Greek states sided with the Romans and invited them across the sea. Second, and more decisive, was the difference in the two military systems. The Macedonian phalanx of pikeman was still a powerful weapon, but it had severe weaknesses. The phalanx needed to stay united, fight on level ground, and could only face an enemy to its front. Therefore it lacked flexibility. This was not a problem until the Macedonians met a people who fought differently. The Roman army was just as well organized and disciplined but more flexible (Polybius,18.32). Its individual soldiers were more autonomous and its officers could take initiative. During the key moments at Cynoscephalae and Pydna this made the difference and wrested rule of the eastern Mediterranean from the Macedonians.