Alexander the Great’s Destruction of the Great City at the Battle of Thebes

Thebes, a city-state rich in mythology and history, was the only Greek city that was entirely destroyed by Alexander the Great in his military campaigns.

Alexander III of Macedonia, more commonly known as Alexander the Great, is one of the most famous military leaders of ancient history for his conquest of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. However, before his campaign in the Persian Empire was fully underway, Alexander had to put down rebellions against Macedonian rule in the Greek city-states his father previously controlled. One of these city-states was Thebes, but Alexander did more than put down a rebellion here.

Background to the Battle of Thebes: Philip II’s Campaign in Greece

Silver tetradrachm of Philip II, artist unknown, 359-355 BCE. Source: the MET, New York

To understand why the destruction of Thebes took place in 335 BCE, it’s important to look back to the campaigns of Alexander’s father, Philip II of Macedon. Most of Philip’s reign was spent expanding his territory and solidifying his power in the Mediterranean, which included bringing areas in the east and north of Macedonia under his control, campaigning in Thessaly and Thrace, and extending his influence into Greece. As Philip began to get more involved in wars in Greece (such as the Sacred Wars), certain city-states opposed his interventions and attempts at gaining military power in Greece.

Lion monument for the Battle of Chaeronea, constructed 338 BCE, image by Jona Lendering. Source: livius.org

Athens and Thebes allied and faced Philip at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338, and it is said that teenage Alexander fought alongside his father’s army during this battle. Philip won this battle and went to Thebes, where he expelled leaders who opposed him and installed a garrison. This would lead to a strained relationship between Thebes and Macedonia that would get worse by 335.

It is worth noting that Philip’s goal in Greece was less about conquering and more about creating a military alliance he could call upon for his planned invasion of the Persian Empire or what would be known as the League of Corinth.

Alexander the Great’s Succession

Alexander Cuts the Gordian Knot by Jean-Simon Berthélemy, 1767. Source: the Louvre, Paris

After his father’s assassination in 336, Alexander, the newly-crowned king of Macedonia, began to amass his power in Macedonia and Greece before continuing with his father’s campaign to conquer the Persian Empire. The process of Alexander consolidating his power included a series of assassinations of potential threats to his reign, handling border skirmishes in Macedonia, and suppressing revolts with his Balkan campaign.

Philip’s death was seen as an opening by many city-states in Greece to break away from Macedonian influence. Athens and Thebes revolted twice within a short time span, once when the news of Philip’s death first spread and again when Alexander was suppressing revolts in the Balkans. The second time led to Alexander pausing in his campaign to return to Greece and face the revolts himself. Many cities, including Athens, were reluctant to engage in battle. However, Thebes decided to confront the new Macedonian ruler.

The Battle of Thebes

Sketch of Thebes by Sir William Gell, 1800-1813. Source: the British Museum, London

The two more detailed accounts of the battle of Thebes can be found in the histories of Arrian, a Roman military author who wrote extensively on Alexander in the 1st and 2nd CE, and Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian of the 1st BCE. Both authors wrote their histories quite a bit after Alexander’s campaign. Nevertheless and despite their limitations, they remain the best sources on the battle of Thebes.

Diodorus Siculus begins by describing the siege on Thebes, which Alexander prepared in only three days. Although the Thebans were greatly outnumbered, they held their own against the Macedonian forces for some time. Diodorus highlights the bravery of the Thebans and how, even when they began to tire, they never considered surrendering. However, Alexander eventually was able to enter the city through an abandoned gate, leading to a mass slaughter of Theban civilians as they tried to retreat further into the city.

Arrian’s account focuses more on strategy and military maneuvers and spends more time explaining how Alexander eventually entered the city. Although he mentions that the entrance of the Macedonian troops resulted in many deaths, Arrian is less concerned with the bravery of the Thebans or the cruelty of Alexander’s men. As Arrian is known to be a great admirer of Alexander, this narrative fits. Interestingly, Arrian highlights how the Greeks and not the Macedonians in Alexander’s army were particularly zealous in killing Thebans. Diodorus made a similar statement about how Greeks were killing other Greeks, but he didn’t suggest that the Macedonians were not involved.

Thebes had requested aid from one of the few city-states opposing Alexander, Athens, but the Athenians were unable to make it on time. Arrian adds that upon seeing what happened to Thebes, the Athenians became fearful of facing a similar fate and decided to halt their resistance.

The Destruction of Thebes by Alexander the Great

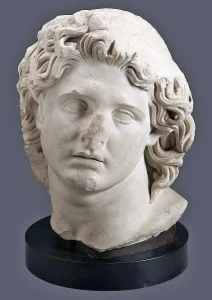

Head of Alexander the Great or Helios, artist unknown, 2nd century CE or 19th century. Source: the MFA, Boston

Alexander and his forces defeated the Theban resistance, killing around six thousand Thebans (according to Diodorus). In many parts of his campaign, Alexander would move on after defeating his opponent, perhaps leaving behind some forces or installing a local leader as ruler. This was not the case in Thebes. Alexander decided to enslave almost all of the survivors, which amounted to over 30,000 Thebans. Some Thebans did escape and tried to receive aid from Athens or local city-states, but their fates are largely unknown. In addition to enslaving and killing most of the population of Thebes, Alexander also decided to raze the city to the ground. There is an anecdote in Arrian that Alexander chose to leave the house of Pindar, one of the most famous Greek poets, but the rest of Thebes was destroyed.

The motive behind the destruction of Thebes and the enslavement of its population has been debated by both ancient and modern scholars. Some, like Diodorus, focus on Alexander’s cruelty rather than the reasons behind it. Arrian suggested that Alexander’s actions at Thebes were meant as revenge for Thebes’ stance during the Battle of Thermopylae, where the Theban forces retreated once the Persian military had gained the upper hand, permanently marring Thebes’ reputation in the minds of other Greeks. Thebes was often suspected of sympathizing with the Persian Empire, which is why Arrian suggests that the Greeks fighting with Alexander were particularly cruel.

Coin of Alexander with eagle on thunderbolt, artist unknown, 336-323 BCE. Source: the British Museum, London

The revenge narrative is also rooted in the public image that Alexander cultivated about himself. Alexander saw himself as the son of Zeus an idea that was reinforced after his visit to the Oracle of Siwa in Egypt later in his campaign. However, even before that, he certainly saw himself as “Greek” (as much as a Pan-Hellenic identity could be given to the collection of city-states at this time). Many Athenians and Thebans rejected this idea, with Demosthenes being a famous example of an Athenian orator who opposed Philip and Alexander, whom he saw as “barbaric.”

Despite some of this push-back, Alexander had a habit of appeasing those he conquered by respecting their religion, maintaining their local leadership, and even dressing in similar clothing. Therefore, Alexander’s decision to destroy Thebes as revenge for their part in not fighting back against the Persian Empire in the Greco-Persian Wars may have appeased some of the Greeks who still saw Thebes in a negative light and promoted a certain narrative in anticipation of his Persian campaign.

Whether this revenge narrative is true or not, it is also likely that Thebes was meant to serve as an example to the rest of the Greek city-states. If Alexander’s military could destroy and enslave an entire city, what would stop them from moving on Athens or Sparta? It seems like his example worked, as any plans Athens had of mobilizing to assist Thebes or revolt against Alexander halted.

The Aftermath of the Battle of Thebes

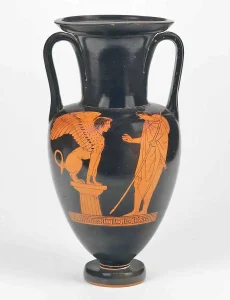

Oedipus and sphinx jar from Theban mythology by the Achilles Painter, 450-440 BCE. Source: the MFA, Boston

Alexander’s destruction of Thebes obscured our knowledge of the ancient city-state. Although Thebes has featured prominently in mythology and other written ancient sources, Alexander’s destruction of the city was so thorough that it hardly left a trace in the archaeological record. Some general information about Thebes can be extracted through archaeology, such as the size of the walls and gates, but as the city was eventually rebuilt following Alexander’s siege, it is now difficult to get a feel for how the city looked like before its destruction.

Although Cassander, one of Alexander’s generals who ruled Macedonia after his death, rebuilt Thebes in 316, the city-state never reached its past glory. Furthermore, the Roman general Sulla conquered the city in 86 BCE, leading to further territorial changes and destruction.

The Founding of Thebes by Salvator Rosa, 1661. Source: the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Whether Alexander’s decision to destroy Thebes and enslave its population was strategic, a chance to get revenge for the Greco-Persian Wars, an outburst of anger, or a combination of multiple reasons, is something that we cannot know for sure. The fact, however remains that the sack of Thebes was a violent event that solidified Alexander’s control over the Greek world leaving him ready to move against the great empire of the East, Persia.