Was Bread the True Cause of an Ancient Egyptian Plague?

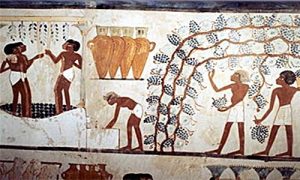

In the shadowy corridors of ancient Egyptian history, an unexpected peril lay hidden within their daily sustenance: bread. At Exeter University, UK, plant pathologist Sarah Gurr unravels the mystery of an ancient plague, pointing to a silent menace known as ergot—a fungus clandestinely infiltrating the grains of rye and wheat. Camouflaged within the very essence of the grain, this fungus found its way into the granaries of the ancient Egyptians, tainting their life-giving bread with a deadly touch.

The contaminated bread, an unwitting harbinger of doom, triggered a cascade of symptoms from sickness and muscle relaxation to convulsions and hallucinations. Yet, the tragedy deepened as the firstborn, cherished and traditionally offered the inaugural morsel at mealtimes, bore the brunt. The very act of safeguarding these precious heirs inadvertently sowed the seeds of their demise. Tales of this calamity, echoing the Biblical account in Exodus of the 10th plague that befell Ancient Egypt, became woven into the fabric of collective memory—a narrative seeking order in chaos, attributing the inexplicable to the divine. The bread that sustained life became an unwitting accomplice in a tale of unforeseen consequences.