A Look Back at the Magical Grimoires’ Ancient History: Spells, Invocations, and Divination

Grimoires are books containing magic spells and instructions for the making of amulets and talismans, but some of them also contained directions on how to summon and control demons. Grimoires have gained great popularity in recent years through movies and television shows, but their origins date back to ancient times, and their full purpose still remains under much speculation. The Oxford dictionary defines a grimoire simply as a book of magic spells and invocations, and these books are usually attributed to famous figures such as Moses and King Solomon.

Owen Davies is perhaps one of the most prominent scholars in the field of magic studies. His book, “Grimoires: A History of Magic Books”(2009), compiles extensive research on the history of grimoires as well as magic. For Davies, grimoires are books of conjurations and charms, believed to have stored knowledge that could protect people against evil spirits, witches, heal illnesses, and alter destiny, to name just a few uses.

The word ‘grimoire’ is believed to derive from the French word for ‘grammar’, the act of combining symbols to create sentences. Grimoires are not magical diaries but a compiled set of instructions intended to produce a specific desirable outcome. Although grimoires are books of magic, not all books of magic are grimoires. Some magic texts were concerned with discovering and using secrets of the natural world instead of focusing on the conjuration of spirits, the powers carried by words, or the rituals involving the creating of magical objects.

Papyrus Scrolls and Magical Practices: Unearthing Ancient Wisdom

Grimoires existed to manifest the desire to create physical records of magical or secret knowledge, and to secure information which could be lost with the oral transmission of valuable information. In addition, the very act of writing was associated with occult or hidden powers. This urge of creating tangible sources to record magical information dates back to the ancient civilization of Babylonia in the second millennium BC, and Egypt also provide us with records of this nature. Large numbers of papyri containing information about magic practices and ceremonial magic have been discovered. Writing on papyrus required the use of ink and it led to a new magical notion based on their constituent. In order to create ink, ingredients such as myrrh, which was also used for some charms, and blood were often used.

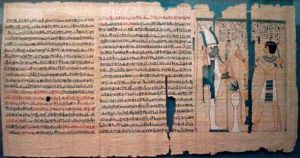

Part of the Book of the Dead of Pinedjem II. (British Museum/CC BY-SA 3.0)

But what exactly constituted a grimoire still remains under debate. Taking, for example, the “Egyptian Book of the Dead”: is it a guided instruction to the soul’s successful path to the afterlife, or is it a collection of spells to be recited at the moment of death when the soul begins the journey to the afterlife to ensure its control over the supernatural entities in which it would come into contact during the journey? Or could it be both? The earliest papyri record of the “Book of Dead” dates back to the fifteenth century BC, but ritual utterances can be traced back even a thousand years earlier. Some of the spells in the “Book of the Dead” originated in the “Pyramid Texts”, which first appeared carved in hieroglyphs on the walls of the burial chamber and anteroom of the pyramid of the last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty, King Wenis, from around 2345 BC.

Magic in the Early Years of Christianity: A Shared Tradition

Although not actually a grimoire, the words in the Bible were believed to contain power, making it one of the widest magical resources across society and culture for a thousand years. Passages from the Bible were used as healing charms and psalms were read for magical effects. By the early years of Christianity, many magic books were in circulation in the eastern Mediterranean among Jews, pagans, and Christians. There is archaeological evidence for such, represented in Graeco-Egyptian and Coptic papyri. While the Church defeated much of the pagan worship during those early years, it never managed to make a clear distinction between magic and religious devotional practices, and medical manuals are an example of this. The so-called leech books contained not only classical medicine but also spells for healing and protection. Some of the charms were Christianized versions of pagan healing verses, and while most of the spells were enacted orally, with the written form only serving as a record, textual amulets were an integral part of the tenth and eleventh century medicine as practiced by clergy and literate lay folk.

The so-called ‘Gospel of Jesus’ Wife’. (Karen L. King/Harvard Divinity School)

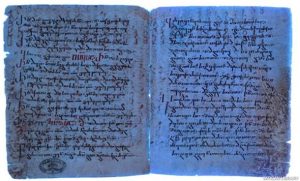

In 2023, Grigory Kessel, utilizing ultraviolet photography, identified a small manuscript fragment in the Vatican Library as the fourth textual witness. This fragment, revealing a double palimpsest as the third layer of text, stands as the sole existing remnant of the fourth manuscript, providing valuable insight into the early transmission of the Gospels within the Old Syriac version’s history.

The hidden texts of the Gospel of St. Matthew are revealed under ultraviolet photography. (© Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana/Cambridge University Press

Grimoires as Cultural Clues: Unraveling Historical Beliefs

During the European Medieval era, the main interest in grimoires resided in the practice of astral magic, which was influenced by Arabic knowledge and based in the idea that the powers from planets and stars could be channeled into talismans and images through the intervention of named spirits and angels, at precise astrological moments. Owen Davies states that “the idea that divine and astral spirit forces could be harnessed by magical means dates right back to the beginning of recorded magic. It was practiced in ancient Babylonia, and Jewish and Indian influences can also be found in the Arabic works”. Medieval grimoires displayed their intentions more clearly, providing the magician with directions towards how and what could be accomplished with the knowledge contained within the words written.

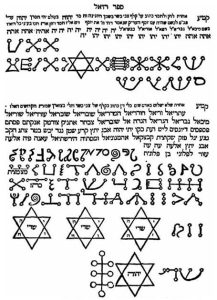

An excerpt from Sefer Raziel HaMalakh, featuring magical sigils. (Public Domain)

It is important to keep in mind that magic, spells, demons and spirits meant something very different for people in the past, who lived in a world surrounded by the unknown. When studying ancient magic and magical practices, one needs to be sensible about those differences and approach the subject with a nonjudgmental mind.

Even nowadays, magic is not easily defined as it means different things to different people at different times and places in the world. In addition, distinction between religion and magic has never being clear in the past eras, and it changed over time and in relation to the various religious systems.

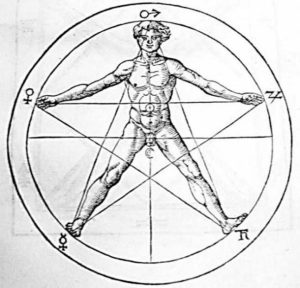

Man inscribed in a pentagram, from Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia (Public Domain)

As Owen Davies beautifully stated, “the history of grimoires is not only about the significance of the book in human intellectual development, but also about the desire for knowledge and the enduring impulse to restrict and control it”. Current scholars acknowledge the importance of studying magic, not only as historical and cultural subject, but also in relation to its connections with medicine and healing. Grimoires can serve as clues to understand the beliefs held by individuals at different points in our history.