Egypt Looks Back: Where Are the Historical Narratives of the Great Exodus?

The biblical story of the Israelites’ Descent and Great Exodus speaks about important events that took place in Egypt. We should, therefore, expect to find records of these events in Egyptian sources. These events include the seven years of famine predicted by Joseph, the arrival of his father Jacob with his Hebrew family from Canaan, the great plagues of Moses, the death of Egypt’s firstborn, including the Pharaoh’s first son, and the drowning of the Pharaoh himself in the Red Sea.

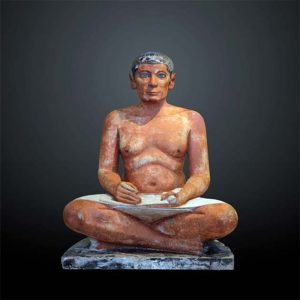

All of these significant events related to the Great Exodus should have been meticulously recorded by the scribes who maintained detailed records of daily life. However, it is noteworthy that no contemporary inscriptions from the relevant period can be found that document any of these events.

Even though Egyptian scribes were tasked with recording important events, there are no records of the biblical story of the Israelites’ Descent or the Great Exodus. The Seated Scribe on display at the Louvre. (Rama / CC BY-SA 3.0 FR)

Unspoken History: The Absence of the Great Exodus in Contemporary Records

In spite of this silence, the name of Israel has been found inscribed on one of the pharaonic stele, although with no connection either to Moses or the Exodus. However, although the Merneptah stele locates the Israelites in Canaan around 1219 BC, it makes no mention of them previously living in Egypt or departing from it in a Great Exodus under Moses.

The complete silence of official Egyptian records regarding Moses and his Great Exodus was eventually broken by Egyptian historians, who appeared to possess numerous details about Moses and the events of the Exodus. It seems that contemporary pharaonic authorities deliberately suppressed any mention of Moses and his followers in their official records.

Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele, is an ancient Egyptian inscription that mentions the Israelites and is housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. (Onceinawhile / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Breaking the Silence About the Great Exodus

Despite this suppression, popular traditions retained the story of Moses, whom Egyptians regarded as a divine figure, for more than ten centuries before it was finally recorded by Egyptian priests. Under the Macedonian Ptolemaic Dynasty, which ruled Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, Egyptian historians made sure to include the story of Moses and his Great Exodus in their historical accounts.

Manetho, the 3rd century BC Egyptian priest and historian who recorded the history of Egypt in Greek to be placed in the Library of Alexandria, included the story of Moses in his Aegyptiaca. According to Manetho, Moses was an Egyptian and not a Hebrew, who lived at the time of Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaten (1405 to 1367 BC). Manetho also indicated that the Israelites’ Exodus took place in the reign of a succeeding king whose name was Ramses.

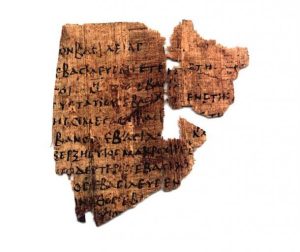

Papyrus from the fifth century AD, suspected partial copy of the Epitome. This was based on Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt by Manetho which includes the story of the Great Exodus. (Public domain)

The Great Exodus As Recorded by Flavius Josephus

Although Manetho’s original text was lost, some quotations from it have been preserved mainly by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in 1st century AD. Commenting on Manetho’s account of Moses, Josephus tells us that:

“Under the pretext of recording fables and current reports about the Jews, he (Manetho) took the liberty of introducing some incredible tales, wishing to represent us (the Jews) as mixed up with a crowd of Egyptian lepers and others, who for various maladies were condemned, as he asserts, to banishment from the country. Inventing a king named Amenophis, an imaginary person, the date of whose reign he consequently did not venture to fix… This king, he states, wishing to be granted… a vision of the gods, communicated his desire to his namesake, Amenophis, son of Paapis (Habu), whose wisdom and knowledge of the future were regarded as marks of divinity. This namesake replied that he would be able to see the gods if he purged the entire country of lepers and other polluted persons.

Delighted at hearing this, the king collected all the maimed people in Egypt, numbering 80,000, and sent them to work in the stone-quarries on the east of the Nile, segregated from the rest of the Egyptians. They included, he adds, some of the learned priests, who were afflicted with leprosy. Then this wise seer Amenophis was seized with a fear that he would draw down the wrath of the gods on himself and the king if the violence done to these men were detected; and he added a prediction that the polluted people would find certain allies who would become masters of Egypt for thirteen years. He did not venture to tell this himself to the king, but left a complete statement in writing, and then put an end to himself. The king greatly disheartened.” (Against Apion by Flavius Josephus)

Josephus was wrong in saying that Manetho invented a king named Amenophis who communicated his desire to his namesake, Amenophis, son of Paapis. This king has been identified as Amenhotep III, 9th king of the 18th Dynasty, while his namesake, Amenhotep son of Habu, is known to have started his career under Amenhotep III as an Inferior Royal Scribe. After being promoted to be a Superior Royal Scribe, he finally reached the position of Minister of all Public Works.

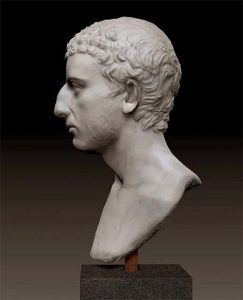

Ancient Roman bust thought to be of Flavius Josephus, dating back to the first century AD. (Public domain)

Understanding Manetho’s Record of the Great Exodus

On the other hand, Manetho’s description of the rebels as being “lepers and polluted people” should not be taken literary to mean that they were suffering from some form of physical maladies. The sense was that they were seen as impure because of their denial of Egyptian religious beliefs.

Josephus goes on to say that for the rebel leader’s first law, he ordained that his followers should not worship the Egyptian gods nor abstain from the flesh of any of the animals held in special reverence in Egypt, but should kill and consume them all. They also should have no connection with any, save members of their own confederacy. After laying down these and a multitude of other laws, which were absolutely opposed to Egyptian customs, he ordered all hands to repair the walls of Avaris and make ready for war with King Amenophis.

As we can see, although contemporary Egyptian official records kept their silence about the account of Moses and the Israelite Exodus, popular memory within Egypt preserved these events and they were transmitted orally for many centuries before being put down in writing. These traditions told about Moses and Joseph, and also told about the shepherds who lived at the borders and were not allowed to enter the Nile valley.

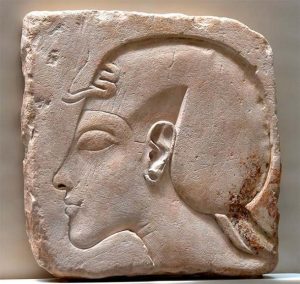

Relief of Akhenaten discovered at Amarna, Egypt, dating back to circa 1340 BC. Could Moses be modelled on his life story? (Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Is Moses Modelled on the Story of Akhenaten?

Manetho could not have invented this information, as he could only rely on the records he found in the temple scrolls. Neither could he have been influenced by the stories of the Bible, as the Torah was only translated from Hebrew to Greek some time after he had composed his Aegyptiaca. As Donald B. Redford, the Canadian Egyptologist, has remarked:

“What he (Manetho) found in the temple library in the form of a duly authorized text he incorporated in his history; and, conversely, we may with confidence postulate for the material in his history a written source found in the temple library, and nothing more.” (Pharaonic King Lists, Annals and Day Books by Donald B. Redford)

On the other hand, Monatho’s dating of the religious rebellion in the time of Amenhotep III, assures us that he was giving a real historical account. For it was during this reign that Amenhotep’s son and co-regent, Akhenaten, abandoned traditional Egyptian polytheism and introduced a monotheistic worship centered on the Aten.

Akhenaten, like the rebel leader, also erected his new temples open to the air facing eastwards; in the same way as the orientation of Heliopolis. This similarity between Akhenaten and the rebel leader persuaded Donald Redford to recognize Manetho’s Osarseph story as the events of the Amarna religious revolution, first remembered orally and later set down in writing:

“…a number of later independent historians, including Manetho, date Moses and the bondage to the Amarna period? Surely it is self-evident that the monotheistic preaching at Mount Sinai is to be traced back ultimately to the teachings of Akhenaten.” (Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times by Donald B. Redford)

In his Pharaonic King-Lists, Redford also confirms that: “The figure of Osarseph/Moses is clearly modelled on the historic memory of Akhenaten. He is credited with interdicting the worship of all the gods, and in Apion, of championing a form of worship which used open-air temples oriented east, exactly like the Aten temples of Amarna.”

As for the starting point of the Great Exodus, while the biblical account gives the city’s name as Rameses, Manetho gives the name of another location: Avaris. Avaris was a fortified city at the borders of the Nile Delta and Sinai. It was the starting point of the road to Canaan, which had been occupied by the Asiatic kings, known as Hyksos, who ruled Egypt from about 1783 to 1550 BC, when they were driven out by Ahmosis I.

As the period when Moses lived in Egypt was identified under Amenhotep III, the starting point of the Great Exodus located at Avaris, and the Pharaoh of the Exodus identified as Ramses I, it seemed like the road opened to start looking for historical and archaeological evidence to confirm this account.

Scholars, however, did not follow this route of investigation, and went on looking for evidence in other times and different locations. Thanks to Flavius Josephus, who wrongly identified the Hebrew tribe—not with the shepherds who were already living in Egypt, but with the Hyksos rulers who had left the country more than a century earlier—modern scholars dismissed Manetho’s account as unhistorical.