Unexpected Connections Between the Jewish New Year and Pharaoh Akhenaten

The origin of Jewish New Year celebrations has long been shrouded in mystery. Families around the world celebrate it during autumn with sweet delicacies, joyous prayers, and the blasting of the shofar ram’s horn. Called Rosh Hashanah (“Head of the Year”), it is also Yom Hazikaron (“Day of Remembrance”). However, what exactly is being remembered? The Bible offers no clue. It is a day of ancient riddles and questions, and simply no one knows its raison d’être.

Searching for the Origins of the Jewish New Year

Scholars agree to its great antiquity, going back to the time of Moses. We first read of the holiday in Leviticus 23:24, where it is called zikhron teru’ah, “a memorial of shouting [or blowing of horns]”, a holy convocation, to be held on the first day of the seventh month. Meanwhile, Numbers 29:1 calls it Yom Teru’ah, or “Day of Shouting [or blowing of horns]”. The day’s three special prayers are for the kingship of God, remembering, and for blowing the shofar.

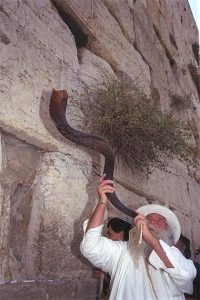

Blowing the shofar at Jerusalem’s Western Wall during the eve of Rosh Hashanah. (Government Press Office (Israel / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Something of great importance must have been memorialized during this celebration, now lost to antiquity. We know it required both shouting and the blasting of the shofar horns, which marked the coronation of monarchs in Israel. At least a dozen ideas have been put forward as to the reason behind the celebration, including remembering the binding of Isaac by Abraham, commemorating the future arrival of the Messiah and God’s final judgement.

During the times of the Talmud (3-6 th centuries BC), Rosh Hashanah was associated with the coronation of God: “Say before me on Rosh Hashanah the “sovereignty” service… so that you can make me king over you” (Rosh Hashanah 16a). This stems from the very ancient Song of the Sea in Exodus 15:18, which states: “Yahweh will reign forever and ever!”

It also evokes the Coronation Psalms which describe God as King, such as Psalms 45, 47, 93, 95, and 97. In Psalms 98:6 we read: “with trumpets and the blast of the ram’s horn – shout for joy before the Lord, the King!” I wonder, however, why it isn’t mentioned in the Torah, if this really was the reason? If Moses meant to celebrate the crowning of God, why didn’t he explicitly say so? I still sense a secret.

What are Jewish families celebrating each year during Rosh Hashanah? What secret event are they so joyously commemorating? I have a radical proposal: They are remembering the coronation of Akhenaten, the monotheistic sun king of the Amarna Age, and, I believe, the secret “King Moses” at the heart of Judaism. I believe we can make the most sense of this puzzle if we connect the Pharaoh Akhenaten to the Hebrew prophet Moses.

The most well-known tradition of Rosh Hashanah is the blowing of the shofar. (rudall30 / Adobe Stock)

Coronation of the Sun King: Linking Akhenaten to the Jewish New Year

The coronation of Akhenaten, then called Amenhotep IV, has been extensively studied and debated by scholars. This is because no explicit text describing the event exists. We know he succeeded his wealthy father Amenhotep III sometime in 1354 BC. We also know the priest Manetho, who lived during the 3 rd century BCE, recorded that Amenhotep III spent seven months of his final year on the throne, and thus his son came to power after seven months of his father’s yearly rule.

This took me by surprise, because the same relationship exists between the start of the religious year, Rosh Hashanah, which falls seven months after the first of the Jewish civic year in spring. Could Rosh Hashanah have been set for the first of the seventh month because that is when Akhenaten came to the throne, exactly seven months after the beginning of his father’s rule?

Several scholars have indirectly researched the accession date of Akhenaten by calculating that of his father. For example, Charles Cornell Van Siclen III carefully analyzed all inscriptions associated with Amenhotep III’s accession, and deduced that it most likely occurred on the first day of the second month of the Shemu, or season of harvest (the “tenth” Egyptian month).

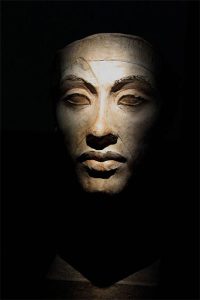

Could it be that Rosh Hashanah originated as a celebration of the coronation of Akhenaten? (HoremWeb / CC BY-SA 4.0)

If his son took the throne seven months after his father’s year began, he would have ascended during the first day of the first month of the season of growth, Peret (or the “fifth” Egyptian month). In other words, his accession day was very likely the first day of the seventh month after the year began (i.e. his father took the throne), or exactly when Rosh Hashanah takes place!

Remarkably, this is independently confirmed by Amarna-expert William J. Murnane, who has argued separately that Akhenaten very likely came to the throne some time during the first eight days of the first month of Peret. During this time, ~1354 BC, this specific date would have fallen sometime in early November, with his father assuming the throne during April.

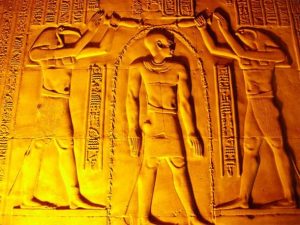

On a lintel from the tomb of the Royal Steward Kheruef (TT192), we see what may be a coronation scene of the young Amenhotep IV, before he changed his name to Akhenaten. The young monarch, depicted in traditional Egyptian proportions and poses, offers wine and incense to the traditional male and female deities Atum, Hathor, Ra-Horakhty, and Ma’at. In the center, over his new royal name we see the ram horns that will later come to typify Jewish shofar horns.

A shofar ritual ram’s horn. (Zachi Evenor / CC BY 3.0)

Shofars, Sheep, and Shouting: Following the Archaeological Evidence

The most well-known tradition of Rosh Hashanah is the blowing of the shofar. During this holy day, the ancient ram’s horn is blown one hundred times to celebrate God and commemorate the beginning of the New Year. However, no reason is given in the Torah. We know in other situations, the blasting of the shofar horns marked the coronation of monarchs in Israel.

Shofars can be made from the horns of many species of bovid, including cattle, sheep, ibex, pronghorn, and even the majestic kudu antelope. Amazingly, excavators working at Akhenaten’s city of Amarna during the 1920s discovered two antelope horns, so similar to modern day shofar horns that they could possibly be history’s first examples. We also see a large tomb scene at Amarna depicting a Nubian contingent offering tribute to Akhenaten: gold, ivory, cheetahs, and most relevant to our study, antelope with long horns. Music was an integral part of life at Amarna under Akhenaten, and these antelope horns would have certainly contributed to the musical milieu.

As Lyn Green comments: “In fact, music in some form or other seems to have surrounded Akhenaten and his family at almost all times when they were in public. It should be seen as the essential element of the cultural revolution that has mystified and intrigued us for well over a century.” We also know from the Amarna Letters (correspondence between Akhenaten and other regional kings) that the King of Mitanni, Tushratta, sent many horns to Egypt for the king: “I set their …. ram-horn … strung on a wire of gold” (EA 25; William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters, 1992).

There were two main types of sheep in ancient Egypt. During the Old Kingdom, the main species was the Ovis longipes palaeoagytiaca. They had long, straight, wavy horns, and were dominant in art for many centuries. For example, the ancient ram-headed god Khnum sported these original wavy horns. This species however became extinct and another species of sheep, the Ovis aries platyra aegyptiaca, became popular past 2000 BC in Egypt. They were characterized by a curved horn, and were most commonly associated with Amun, god of Thebes.

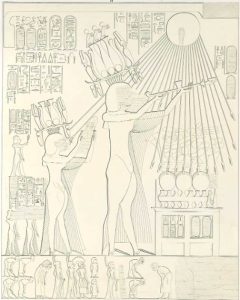

Image of Akhenaten and Nefertiti making an offering to the Aten, taken from the tomb of Panehsy in Amarna. Akhenaten and Nefertiti both wear elaborate new plumed crowns featuring sun disks, protective cobras, and ram horns. These hemhem crowns, or “Crowns of Shouting”, were associated with the joyous rising sun and rebirth, and their ram’s horns are reminiscent of modern Jewish shofar horns. (Lepsius / Public domain)

We know from inscriptions that Akhenaten favored the older, long, wavy horn of the Ovis longipes palaeoagytiaca species, associated since the Old Kingdom with the Pharaoh, the gods, creation, and most importantly, the sun. The horns were associated with the Atef crown, first worn by the Old Kingdom sun pharaohs Sahure and Nyuserre during their Sed festivals – coronation-esque ceremonies of the king’s renewal and rebirth as a solar divinity. These powerful pharaohs inspired the young king, who re-imagined their ancient headpiece as a new crown, the triple Atef, or hemhem.

The new hemhem crown incorporated ostrich feathers, sun disks, cobras, and twisted ram horns, and it memorialized the rising sun and rebirth, both common New Year’s themes. Its name even translates to “shouting out”, nearly identical to the Biblical name of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Teru’ah, or “Day of Shouting”.

Why shout on Rosh Hashanah? Well, “mighty shouts of joy” always accompanied a king’s coronation in ancient Egypt and Israel. For example: “they blew the shofar and shouted, “Jehu is king!” (2 Kings 9:13). Also, we read from the Coronation Inscription of Pharaoh Horemheb (translated by Sir Alan Gardiner) that: “the entire people were in joy and they cried aloud to heaven. Great and small seized upon gladness, the whole earth rejoiced.” Keep in mind that Horemheb helped restore Egyptian religion after the Amarna regime.

May Your Name Be Written: The Importance of a Name

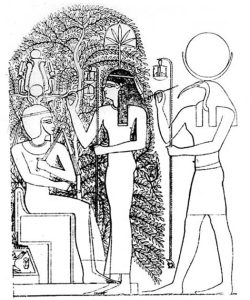

During the coronation, the new names of Pharaoh were written on the leaves of the Tree of Life in Heliopolis. They were also inscribed in the Book of Life, a scroll known as the Book of the Dead, that was written to magically help the monarch achieve eternal life: “I shall not die, but live!” (Psalms 118:17). Names in ancient Egypt were of utmost magical importance, and, as Matthew Militza notes, “the knowledge of the name of a god or of a man gave the magician complete power over him.” From an Amarna tomb scene, we see Akhenaten and Nefertiti offering the royal name of the Aten, in cartouches, to the eponymous sun disk, emphasizing the importance of the royal name of God.

Now, thousands of years later, these themes of kingship and name-power still resound during the New Year. For example, the famous Rosh Hashanah prayer Avinu Malkeinu calls God “Our Father, Our King.” Also, the most important greeting during Rosh Hashanah is l’shana tova tikateyvu, or “may your name be written for a good year”. Where is your name written? Both in God’s Book of Life ( Sefer HaChaim) and on his Tree of Life ( Etz Chaim). This is immortalized in Psalms 72:17: “May the king’s name endure forever; may it continue as long as the sun shines.”

The name of the new Pharaoh is written on the leaves of the sacred Ished tree of Heliopolis by the gods Seshat and Thoth during the coronation. From the Ramasseum, mortuary temple of Ramses II. (Public domain)

A person’s name is very important during the holiday, with the hope that through confession and repentance of sins, their name can be salvaged and restored by being written both in the Book of Life and on the Tree of Life. This is an echo of the sacred Ished tree of life in Heliopolis on which Pharaoh’s names were symbolically written during his coronation. Heliopolis was the ancient city of the sun, revered by Akhenaten, and even appears in the Torah as the adopted home of Joseph, who married the daughter of a High Priest of Ra.

A Mystery Celebration Three Millennia Later: The Conflation of Two Icons?

Stephen D. Ricks and John J. Sroka describe twenty-seven elements of ancient coronation rituals in ancient Egypt. Remarkably, most of them correspond toh the celebrations of Rosh Hashanah. First, ceremonial washings were believed to avert evil, give life, and symbolize rebirth of the king. We see this ritual in many temple scenes which depict the Pharaoh being covered by the gods in the “waters of life”.

We know similar washing rituals were very common at Amarna. Remains of lime-plastered washing basins have been excavated, and tomb inscriptions depict ritual washing pools with twin sets of stairs. These are strikingly similar to both ancient and modern Jewish mikva’ot (stepped ritual baths), which often have different entry/exit routes so as not to mix washed from unwashed people. Washing in the mikveh, meanwhile, remains an important custom just before Rosh Hashanah.

The gods Thoth and Horus pour life giving waters over the head of Pharaoh Ptolemy VI to purify him before he takes the throne of Egypt; in a scene from the Kom Ombo Temple, southern Egypt. This is similar to the purifying ablutions that Jews perform before Rosh Hashanah. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another element discussed by Ricks and Sroka is that the king is symbolically reborn during his coronation, while Rosh Hashanah celebrates the rebirth of nature, the year, and our souls. Other connections include: feasts, secrecy, pure white garments, and the placing of the crown, which is today called the keter torah and is placed onto the “head” of the Torah scroll itself.

Ricks and Sroka finally draw attention to larger themes that underlie coronation rituals, and which also connect to modern Judaism. They were generally connected to the priesthood, they took place in a sacred space, such as a Temple, and the monarch was generally a priest as well, or “endowed with priestly power.” These all echo modern themes of Rosh Hashanah, where the services occur in the synagogue, the holiest place of Jewish prayer and the successor institution of the Jewish Temple, where the priests administered the sacrifices and other rites according to the Torah of Moses.

A silver Torah scroll crown, or keter. I believe the focus on the “crown of the Torah” and the “crown of God” during Rosh Hashanah hint at a secret ancient coronation that occurred during this day – that of Akhenaten. (Metropolitan Museum of Art / CC0)

During the Old Kingdom, regnal years of Egyptian kings were determined by the founding of temples, and also country-wide censuses (i.e. the “Year of the Nth Counting”), while during the Middle Kingdom, they were subsumed into the civic calendar. By the New Kingdom however, the regnal years of kings were reckoned from their accession days. In other words, “each new year began on the anniversary of their accession without regard to the beginning of the civil calendar.”

This eventually became an established part of the later Israelite monarchy, and is still, I believe, preserved in Rosh Hashanah, or the “New Year that began on the anniversary of the accession of Akhenaten.” Since there is no logical reason why the first of the seventh month should be regarded as a holy New Year, I submit it is because it recalls the accession of Akhenaten on the first of the seventh month of his father’s reign, marking the beginning of a new reign and a New Year.

Could Jews still be secretly celebrating the coronation of Moses, the secret king at the heart of their religion? An ancient passage from the Torah may hold a clue. Called the Blessing of Moses, it concerns the eponymous leader blessing each Israelite tribe in turn. However, one verse stands out: “He (Moses) was king over Jeshurun, when the leaders of the people assembled, along with the tribes of Israel” (Deuteronomy 33:5). If Moses was once, long-ago, conceived of as a king, then it makes all the more sense that Rosh Hashanah is secretly celebrating his coronation.

Every fall during the New Year’s celebration, the shofar is sounded to remind Jews to remember a forgotten event, and to commemorate it with shouting and joy. If this momentous yet thoroughly mysterious celebration really hides the seeds of a Pharaonic coronation somehow lost over the course of three thousand years, then it would strongly suggest that Akhenaten did indeed live on to become Moses, thereby preserving his revolutionary monotheism for untold countless future generations.