Unknown Links Between Pharaoh Akhenaten and Yom Kippur

As Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar approaches, this article delves into the religious traditions that are followed by millions at this time of year. But it goes further, noticing that some of the traditions seem to correlate very neatly with some more ancient customs of Egypt. What rituals and traditions found in the time of Pharaoh Akhenaten could have fed into the books of the Jewish faith?

A lone Memorial candle is lit. The sun finally sinks below the horizon. Food and drink are put away, and all the past year’s mistakes, sins, and transgressions weigh heavily on the hearts of the Jewish people. The holiest day of the Jewish year, Yom Kippur, has officially begun.

The name means “Day of Atonement”, and it is a somber day of confession, repentance, and ultimately forgiveness. It occurs ten days after Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and millions of Jews around the world celebrate it each year by praying in synagogues, fasting, confessing their sins, and asking for forgiveness from God.

More Jews attend synagogue on this day than any other, confirming their connection to a long distant, and in most cases mysterious past. The focus of the day is on spiritual renewal and well-being, during which physical pleasures are denied – the five main ones being: eating and drinking, wearing leather, bathing and shaving, anointing with oils, and having intimate relations.

“Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Yom Kippur”, by Maurycy Gottlieb, 1878; oil on canvas. (Public Domain)

The first instance of Yom Kippur comes from the Torah, in Leviticus 16:29-31. Moses commands the Israelite priests and citizens concerning the Day of Atonement:

29 “This is to be a lasting ordinance for you: On the tenth day of the seventh month you must deny yourselves and not do any work—whether native-born or a foreigner residing among you— 30 because on this day atonement will be made for you, to cleanse you. Then, before the Lord, you will be clean from all your sins. 31 It is a day of Sabbath rest, and you must deny yourselves; it is a lasting ordinance.”

Atonement was originally achieved through ceasing work, fasting, and animal sacrifices in the Tabernacle of Moses, and later the Jerusalem Temple. Once the Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD, the Jewish community was forced to shift their focus onto non-sacrificial means of atonement, principally: repentance, prayer, and charity.

The sacred day is also cloaked in mystery, especially concerning its origins. Scholars point to it emerging very early, perhaps as early as the 8th-7th centuries BC. However, I believe that it, along with Rosh Hashanah, connects all the way back to ancient Egypt, specifically the period of religious heresy under the pharaoh Akhenaten in the 14th century BC, whom I have argued was also the Hebrew prophet Moses. If true, then so many mysterious Yom Kippur traditions may be explained. Let us examine several of them to better understand.

A Jew participates in the Kol Nidre prayer on the Eve of Yom Kippur; “Kol Nidre”, by Wilhelm Wachtel, circa 1900. (Public Domain)

The Book, the Balance, and the Beating of the Heart

A common Jewish belief is that a person is inscribed into God’s “Book of Life” on Rosh Hashanah, the New Year, and then sealed in that book ten days later on Yom Kippur. For the ten days in between, a person is supposed to ask for repentance, to “tip the scales towards righteousness”.

This is accomplished through three ways: teshuvah, tefilah, and tezedakah (repentance, prayer, and charity). A common expression during these days is therefore: G’mar chatimah tovah, meaning “May you be sealed (in the Book of Life) for a good year ahead.”

This idea of a Book of Life goes back to ancient Egypt, whose people were avowed resurrectionists. They believed the soul and body would be eternally preserved in the afterlife, and that wrong actions and thoughts during life would interfere with this process, potentially damning a person. The Egyptian Book of Life was actually a manual for the deceased, what we call the Book of the Dead, but they called the Book of Coming Forth by Day. It contained spells to help a person achieve eternal life.

During the New Kingdom period, every citizen of Egypt hoped to be buried with some version of this important papyrus, which would have contained the supplicant’s name along with instructions for making it through to the eternal realm. It was of utmost importance that every Egyptian had his name literally inscribed on this magical papyrus to ensure his eternal life, a true Book of Life.

This idea was modified slightly in Judaism, which depicted God as having a heavenly Book of Life. For example, after Moses discovered his people sinning before the Golden Calf, he convinced them that he could atone for them, pleading with God:

“So Moses went back to the Lord and said, “Oh, what a great sin these people have committed! They have made themselves gods of gold. 32 But now, please forgive their sin—but if not, then blot me out of the book you have written.” (Exodus 32:31-32).

This implies that Moses, already at this early time, believed God to have a heavenly book in which he recorded everything.

Amazingly, Akhenaten revered writing and language perhaps more than any other Pharaoh, stressing the connection between writing and life that was an already familiar Egyptian motif. From the earliest days, scribes and priests read and wrote in the Per Ankh, or “House of Life”, and scrolls were kept on all topics of magic, religion, medicine, science, math, and astronomy. When excavating at Amarna in the early 20th century, John Pendlebury and his team discovered many mud bricks stamped with different city locations. Many were for the “House of Life”.

According to tradition, God decides each person’s fate for the coming year on Yom Kippur. This was exactly what the Egyptian Book of the Dead was designed for: to ensure a positive judgement. Even more amazingly, the heart of the supplicant was the focus of his confession and repentance. The heart was the most important organ of the body to the ancient Egyptians. It represented the seat of consciousness and good versus evil. When a deceased person asked to be admitted into eternal life, his or her heart would be weighed against a feather of truth.

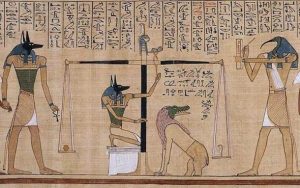

Perhaps the most famous scene in the Book of the Dead, the “Weighing of the Heart” ritual, performed by Anubis and recorded by Thoth, on the right. The heart of the supplicant (red) is placed on the Scales of Ma’at, or the “Scales of Justice” to be weighed against a feather of truth. If a person’s heart was “heavy” with unrighteousness, it was devoured by Ammit, the crocodile-headed hybrid monster. If “light” with purity, then the individual would live forever. This connection between the heart and righteousness was an ancient Egyptian feature and remains a modern Jewish one. From the Papyrus of Hunefer , now in the British Museum. (Public Domain)

Modern Jews practice confession and repentance as part of their daily prayers, but only on Yom Kippur does it form a central part of the services. Confession in Judaism is called viddui, and it is an ancient practice. On Yom Kippur, the High Priest was to confess the sins of the entire land, sending the “scapegoat” away into the desert. The Viddui prayer involves Jews reciting their sins aloud, all while rapping their chests with their fists for each transgression. This is to symbolize punishment for their hearts, the seat of compassion and wrongdoing. An elongated confession, the Al Cheyt, is performed only on Yom Kippur, in which Jews confess to forty-four mistakes they have committed. This recalls the famous list of 42 negative confessions from Spell 125 of the Book of the Dead.

The Jewish concept of the heart is identical to the ancient Egyptian’s (i.e. their “innermost being”) – which is why it was “weighed” to determine a person’s sins. A heavy heart was a sinful heart, while a pure heart was lighter than a feather. Consider the types of sins the Akhenaten’s Chamberlain Tutu connects with the heart, or his “innermost being”:

“My voice is not loud … I do not swagger … I do not receive the reward of wrongdoing in order to repress truth falsely, but I do what is righteous … I do not set wrongdoing in my innermost being …” From the tomb of Ay: “I was straightforward and true, devoid of rapacity … My greatness was in being close-mouthed … a possessor of character, fortunate, joyous, patient … my abomination is lying.”

We can therefore see in the Egyptian Book of Coming Forth by Day many important Yom Kippur themes: the focus on writing in general and more specifically the writing in a “book of life” of a person’s name to ensure a blissful eternity. Other motifs include God’s divine judgement using the heavenly scales, the multiple confessions of lying, loudness, rapaciousness, and haughtiness by the supplicant, and the focus on the heart as the seat of both sin and salvation.

A hand-written Sefer Torah, or Torah Scroll, with a yad pointer stick before it. Now in the State Library of Victoria. (Azoma, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Kippur and the Cake

Many connections back to Akhenaten can be found in the symbolic foods associated with Yom Kippur, including fish, honey cakes, and fowl. While the day of Yom Kippur itself requires total fasting (in order to focus on spiritual healing), before and after the fast are marked by traditional foods, many of which have secret ties back to Akhenaten and Egypt.

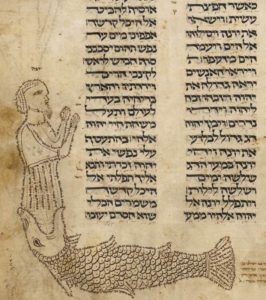

For example, fish is customarily served on Rosh Hashanah and when the Yom Kippur fast is finished, for the big break-fast meal. Smoked salmon, whitefish, and herring are staples (along with bagels and cream cheese). One store in New York, Russ and Daughters, are busiest during the High Holy days, and hand-slice over 8,000 pounds of smoked fish each year. The story of Jonah is also read during Yom Kippur. Its message of rejection of God followed by eventual repentance by the prophet Jonah echo the holiday’s themes, and the tool of God’s teaching was a giant fish!

“Jonah and the Fish”, micrography of Jonah being swallowed by the fish, at the text of Jonah, the ~haftarah~ for the afternoon service of Yom Kippur. British Library / Public Domain)

Fish represents fecundity, rebirth, and regeneration, and are the most common symbol in Jewish folk art. They were the first living creatures mentioned in Genesis as created by God:

“So God created the great creatures of the sea and every living thing with which the water teems…” (Gen 1:21). Compare this to Akhenaten’s Great Hymn to the Aten: “Fish upon the river leap up in front of you, and your rays are within the Great Green Sea (i.e. the Mediterranean).”

Beautiful polychrome glass fish-form vessels have been recovered from Amarna, as have inscribed building blocks that depict fish being skewered in ponds. There are other scenes of Akhenaten and his entire family enjoying sumptuous meals of fish and fowl, looking exactly like a modern Jewish Yom Kippur break-fast meal.

A polychrome glass fish-form vessel recovered from Amarna, now in the British Museum. (British Museum)

Another traditional Yom Kippur food item is the Lekach honey cake (which comes from the German word lecke, meaning “lick”). On the eve of Yom Kippur, before the fast officially begins at sundown, it is customary for children to ask their Rabbi for a piece of honey cake, to symbolize the sweet new year of purity and renewal ahead. These sweet treats are also handed out during the evening to Jewish communities, a tradition begun by the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

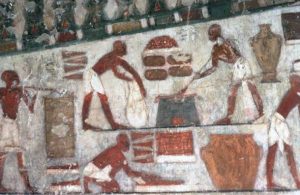

Amazingly, if we go back to ancient Egypt, we find honey cakes were a famous dessert treat for royalty and commoners alike. From the tomb chapel of the Vizier Rekhmi-Ra, we see inscriptions showing men preparing and baking these cakes, using honey, tiger nuts, dates and fat. We read about honey pastries from the tomb of Huya, Chief Steward to Queen Tiye, Akhenaten’s mother. Honey itself was a royal food, for Pharaoh was called He of the Sedge and the Bee.

A painted scene from the Theban tomb chapel of the vizier Rekhmire (15 th century BC), showing, among other activities, the production of honey cakes from tiger nuts for the treasury of the god Amun. From: the Logitudinal Hall, Eastern Wall, Zone 1, Tomb Chapel of TT100, Thebes. (Thierry Benderitter, www.osirisnet.net)

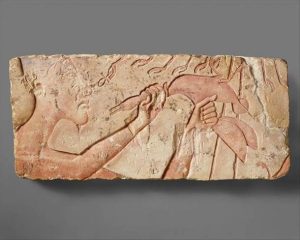

Finally, a third connection concerns birds. A common tradition on the eve of Yom Kippur is the kapparot ritual. It derives from the Hebrew root word k-p-r, meaning ‘to atone’, which is the same root used in Yom Kippur. It is an atonement ritual in which a Jewish person waves a chicken over their head before sacrificing it, symbolically substituting the bird’s life for their own.

Its origins are obscure and controversial, but likely date back very early, since bird sacrifice is mentioned in the Torah of Moses. We read in Leviticus 1:14: “‘If the offering to the Lord is a burnt offering of birds, you are to offer a dove or a young pigeon…” I believe the seeds of this ritual were planted by Akhenaten, who can be seen in an inscription waving a duck before sacrificing it, in exactly the same posture as modern Jews performing the ritual (chickens were not introduced into Egypt until the Roman times, so ducks were the fowl of choice).

Inscription on limestone talatat block showing Akhenaten offering a duck before the rays of the Aten; now in the MET, Ascension #: 1985.328.2. Please see this site for further images depicting how this scene would have originally appeared. (Met Museum)

Your Name Will Be Remembered Forever

A central feature of the Yom Kippur liturgy involves the Yizkor, or Remembrance Service. It involves lighting a special 26-hour candle to burn as a memorial for the deceased members of Jewish families, so that God will remember the souls of family and friends that have passed on. It is meant to renew and strengthen the connections between the living and the dead, in order that we may never forget those who have gone before us.

Interestingly, these were all common concepts in ancient Egypt: remembering the dead, reciting their names, lighting lamps and incense, and offering them spiritual sustenance to help their souls. Ancestors were provided food and drink and prayers at their tomb chapels by their offspring, so that their souls could continue in the afterlife in peace and bliss. Perhaps the most important quality of life to an ancient Egyptian was to be remembered. To be forgotten was to “die again”.

Listen to some Amarna texts:

“May you grant that my spirit may belong to me, lasting and enduring in the fashion of when I was on earth,” and “May you be united with your place of eternity, and may your mansion of eternity receive you,”, and “May the Aten grant the permanence of your resting in your tomb, and that one may pronounce your name continually forever.” How similar this sounds to 2 Samuel 7:26: “And may your name be honored forever.”

The Hebrew letter samekh, the “circle letter” and symbol of the eternity of God; superimposed on the Aten sun disk (author provided). Based on: (Plate XXXI, from Davies, N. de G., The Rock Tombs of El Amarna: Part IV, Tombs of Penthu, Mahu, and Others. (London, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1906).

The Circle of Life

The three main themes of the Yom Kippur liturgy are: forgiveness, pardoning, and atonement. In Hebrew, this acronym spells samekh, the Hebrew letter called “the circle letter”. Curiously, the circle symbolizes many themes of Yom Kippur: the “circling back” to God of repentance and atonement, the return to purity, the unity of the past with the future, the crown of God, and even the endless joy of Yom Kippur. It also echoes the circle of the ankh symbol for life, as well as the Aten sun disk at Amarna, a city replete with themes of light and joy. The Aten even circles the Earth, according to the Amarna text: “Great Living Aten … lord of everything the Aten encircles …”

Jewish girls dance in white linen gowns. Although this is during a Shavuot festival (at Kibbutz Gan-Shmuel), similar joyous religious dancing occurs throughout the year and also on Yom Kippur, the most joyous day of the Jewish year. Many features connect back to Akhenaten: pure white linen gowns, joyous dancing and rejoicing in God, and including everyone, even the children (Amos Gil / CC BY 2.5).

Dancing in ancient times was often done in circles, to represent the complete circle people made during the year, ultimately coming back to God. Mishnah Ta’anit 4:8 recalls how young singles would don white garments and dance, hopefully meeting that special someone with which they could begin a family. Therefore, Yom Kippur was never originally a day of suffering, but of joy.

Rabbi David Evan Markus explains:

“That’s why Yom Kippur—even in solemnity—also is for light, joy and circle dancing. It’s why my synagogue will observe Yom Kippur in traditional ways, and also with dancing. On this Yom Kippur, may we all join the ancient circle dance of light, joy and atonement for a truly good and sweet new year!”

Incredibly, we find evidence for this motif buried within the very name of the holiday itself. The Torah calls the day Yom Ha-Kippurim. While this is usually translated as “Day of the Atonements”, it can also mean “Day like Purim”, which has long been regarded as Judaism’s most joyous holiday.

This was yet another theme of Akhenaten at Amarna: joy. The Egyptian word for joy or rejoicing was hai, and the king had areas of his temples called Per Hai, or “Houses of Joy”. They were filled with musicians and singers extoling God, just like the courts of later Israelite kings.

Yom Kippur officially ends with the blowing of the shofar horn, marking an end to prayers, penance, and the proscription on all food and drink. The final lone blast stretches out across the people of the synagogue, illuminated by the last rays of the setting sun, marking the end of the day. “You set beautifully, O Living Aten, lord of lords, ruler of Egypt” (Ahmose tomb inscription).

We will delve deeper into the many fascinating connections between Akhenaten and Yom Kippur in part II.