Past the Aztecs: The Ignored and Magnificent Purépecha Empire

When talking about the major Mesoamerican civilizations, the Aztecs and Maya tend to dominate the conversation. But Mesoamerica refers to the region in the Americas that stretches from central Mexico to Honduras and Nicaragua, encompassing various indigenous cultures, a region which has historically been home to multiple thriving civilizations. One of these is the often-neglected Purépecha Empire, also known as the Tarascan civilization.

The Purépecha ruled over much of Western Mexico in modern-day Michoacán and their empire covered 75,000 square kilometers (29,000 sq mi). This made it second in size only to the Aztecs. Remembered for their impressive achievements in agriculture, architecture and metallurgy, the Purépecha were one of the greatest Mesoamerican cultures the region has ever seen.

The Purépecha Empire – A Civilization Rivalling the Aztecs

Today the Purépecha are an indigenous people that mainly live in the highlands of central Michoacá, west of Mexico City, but they once controlled one of Mesoamerica’s greatest empires. Their long and impressive cultural history stretches back more than 2,000 years.

Tracing their history hasn’t always been easy thanks to the fact they had no system of writing (unlike the Maya and Aztecs) and has mostly been done so through piecing together the archaeological record as well as using local oral tradition. The Relación de Michoacán by Heronimo de Alca, a 17th-century friar, is also particularly useful.

In its earliest days, the Purépecha civilization started out in central and northern Michoacán and was based around the Zacapu, Cuitzeo and Pátzcuaro which can be found in Western Mexico today. The civilization quickly grew and between 150 BC and 350 AD—a period known as the Late Pre-Classical period—it became quite sophisticated, developing a centralized political structure. By the Middle Post-classic period (1000-1350 AD) it had developed social stratification, like a class system where different tribes held distinct levels of importance.

The Pyramids of Tzintzuntzan: Vestiges of the Purépecha Empire

Hernan Cortes: The Conquistador Who Beat the Aztecs

Towards the end of this period the Wakúsecha were the most powerful and it was one of their chiefs, Taríakuri, who founded the Purépecha Empire’s first (but not last) capital, Pátzcuari city. It was Taríakuri who laid much of the groundwork for the later empire. In 1300 he led the first conquests aimed at expanding his people’s borders and created a ruling dynasty by placing his sons Hiripan and Tangáxua as lords of the Purépecha’s next biggest cities, Ihuatzio and Tzintzuntzan. When he died in 1350 Hiripan took the lead and led conquests into surrounding territories, like Lake Cuitzeo.

Led by the Wakúsecha, the Purépecha civilization’s territory rapidly grew until it was almost double its original size. An administrative bureaucracy was created which split responsibilities and demanded tributes from each state and conquered region, these were ruled over by Purépecha lords and nobles. More land meant more maize, obsidian, basalt and pottery production, which in turn allowed the civilization to grow in power even more quickly.

This early growth turned out not to be sustainable, however. During this time, the waters of one of the lakes the civilization was based around, the Pátzcuaro, began to rise, flooding the lands surrounding it. As people fled, the population became more focused in other areas, leading to increased competition for resources.

Many of them fled to the higher lands of the Zacapu and soon 20,000 people were inhabiting just 13 sites. This is nothing by today’s standards, but it was a major problem back then. As the states that made up the Purépecha civilization vied for resources (and space) it led to instability among the ruling tribes.

The Purépecha that the Lake Pátzcuaro was the center of the cosmos. (memotlacuilo / Adobe Stock)

The Golden Years of the Purépecha Empire

Despite these hiccups the Purépecha empire wasn’t going anywhere for a while and would only grow on the foundation laid by Taríakuri. The Purépecha empire arguably peaked between 1350 and 1520 AD. During this golden era, also known as the Tariacuri phase, the capital moved from Pátzcuari city to Tzintzúntzan, which was located on the north-east part of the same lake.

This capital, and the 90 or so other cities that surrounded the lake, were controlled by the ruling elite via a highly centralized political system. The capital sat at the center of the empire and was its administrative, commercial and religious hub. At the very top sat the Kasonsi (a.k.a. king) along with the rest of the Purépecha nobility, to whom he delegated.

The nobility was split into three groups: the Royal family, the upper and lower nobility. The Royals mainly lived in the Royal Palace in the capital, but some lived in Ihuátzio. Control of the states was then split between the upper and lower nobility who managed the day-to-day running of the empire.

Under this system the Purépecha Empire’s population exploded. The basin of Lake Pátzcuaro was home to around 80,000 people with the capital alone holding somewhere close to 35,000. To keep this growing population fed and water the Purépecha became experts in irrigation to make sure local agriculture could keep up.

The ruins of Tzintzúntzan in Mexico, once the center of the Purépecha empire. (Marcos / Adobe Stock)

Top-Down Economy and Trade in the Purépecha Empire

The empire’s tribute system mostly made sure there was enough food and water to go around with a network of markets and foreign imports filling in the gaps. These markets also made sure there were enough basic materials (like pottery shells and metal) as well as labor to go around. Everything from basic produce like vegetables and flowers to tobacco, fast food and crafts could be procured at markets as well as raw metals like obsidian, copper and bronze.

The most valuable materials, like gold and silver, on the other hand, were strictly regulated by the ruling elite. The Purépecha state owned and controlled all the gold and silver mines, mainly in the Balsas Basin and Jalisco. Few people got to work with these materials and those who did, extremely skilled craftsmen, were most likely kept in Tzintzúntzan’s palace complex where a close eye could be kept on them. Purépecha royal tombs have been found absolutely stuffed with fabulous bronze, silver and gold jewelry.

The Purépecha were some of the foremost metallurgists of pre-Conquest Mexico and exported much of what they produced to other parts of Mesoamerica. Purépecha artisans were responsible for making and exporting the copper bells that played a significant role in many Mesoamerican religious rituals between 650 and 1250 AD.

All industry in the empire, whether it be mining, smelting, forestry, fishing or manufacturing was state controlled to some extent or another. To what extent is a matter of debate and likely changed depending on who was king. It seems that much of the time, as long as the rulers got their tributes on time local communities were largely left to their own devices. The empire was made up of many different ethnic groups and each was allowed to keep its own language and cultural traditions.

Copper bell similar to those discovered at the Purépecha site of Tzintzúntzan. (Public domain)

Purépecha Worship: Understanding the Purépecha Pantheon

As was the case with the vast majority of Mesoamerican civilizations, the Purépecha religion was polytheistic and they worshipped a large pantheon of deities. Their prime deity, however, was their sun-god known as Curicaveri/Kurikaweri.

Worship of these gods was coordinated by another social class; priests. These were led by a Supreme High Priest, an immensely powerful figure, and could be pointed out by the tobacco gourd they traditionally wore hung around their necks.

The Purépecha literally believed their empire was the center of the universe. To them the Pátzcuaro basin they had centered their empire around was the center of the cosmos. Their cosmos was made up of three parts: the sky (where most of the gods lived), the earth (mortal realm) and the underworld (self-explanatory).

In Purépecha mythology, Curicaveri/Kurikawer ruled over the sky realm alongside his wife, Kwerawáperi who was an earth-mother goddess. They had numerous children but the most important was their daughter, Xarátenga- goddess of both the moon and sea.

As mentioned earlier, the Purépecha empire was made up of numerous ethnic groups especially as it swallowed up more and more regions over time. It’s believed their religion took the Roman approach, appropriating the deities of conquered peoples and adding them to their pantheon.

Rather than diluting their own religion, this process (known as syncretism) came with several upsides. This cultural blending helped to maintain social cohesion and contributed to a sense of unity and stability, vitally important when ruling over an empire made up of such a diverse group. This symbolic integration through the inclusion of foreign deities may also have been a way for the Purépecha to signal a shared identity among diverse communities and foster a sense of unity.

Worship of the Purépecha was similar in form to the religions of other Mesoamerican cultures. Curicaveri/Kurikawer was usually worshipped in rituals that included burning wood, bloodletting and even human sacrifices. To honor the gods, five pyramids were built at Tzintzúntzan and five at Ihuátzio.

The most impressive of these are found at Tzintzúntzan. These rather unique structures don’t use the traditional stepped-pyramid design, like those of the Aztecs and Maya. Instead, the main ceremonial center at Tzintzúntzan includes five rounded platforms arranged in a Y-shaped configuration.

These platforms are known as yácatas. Each yácata is a pyramidal structure with a flat, circular or oval summit. These structures served various ceremonial and religious purposes, including the performance of rituals and the display of religious symbols. Excavations inside them have revealed they were used as tombs and have been found to hide a treasure trove of artifacts.

And it wasn’t just their pyramids which made the Purépecha stand out from their other Mesoamerican rivals. Unlike most religions in the area, the Purépecha didn’t have a rain god (like the Aztec’s Tlaloc), nor did they have a feathered serpent god (like the Aztec’s Quetzalcoatl). Similarly, they had their own distinctive calendar, which included an 18-month solar year in which each month was 20 days long, opposed to the 260-day calendar used by their neighbors.

Were the Purépecha and the Aztecs Frenemies?

The Purépecha Empire’s biggest rivals were the Aztecs, their neighbors to the southeast. As both empires grew, they began to compete for both resources and territory. Amazingly however there is shockingly little evidence to indicate the two ever engaged in all-out war. Why?

It may well have been a case of an unstoppable force meeting an immoveable object – neither empire was willing to take on such a potentially powerful enemy. We know a meeting of the two powers at Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) in the 1470s led to a treaty in which both sides agreed on a north-south border between the Lerma and Balsad Rivers.

Both the Aztecs and Purépecha seem to have lined this region with fortifications to ensure neither side reneged on the agreement. One of these fortresses, Acambarao, has proven to be our best source of information on Purépecha military power.

While likely not as big as the Aztec’s army, we know that the Purépecha maintained a standing, professional army with soldiers who were trained and dedicated to military service. They were also well-equipped, carrying a variety of weapons, including macuahuitls (wooden swords embedded with obsidian blades), atlatls (spear-throwing devices), slingshots and copper or bronze axes. This impressive standing army was bolstered by soldiers tributed to the Purépecha by regions they had conquered.

This all helps to explain how the Purépecha managed to dissuade the mighty Aztecs from trying too hard to conquer them. In fact, there’s some evidence to suggest the two empires sometimes traded, even if they weren’t exactly on friendly terms. Along the border local tribes acted as intermediaries between the two powers, especially at the frontier trade city of Taximoroa. The archaeological record also indicates that there was at least some cultural exchange and some Purépecha pottery has been found in Aztec held lands and vice versa.

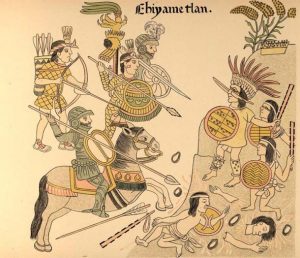

When the Spanish discovered they had been duped by Tangáxuan II, they sent the ruthless conquistador Nuño de Guzmán who had the Purépecha leader overthrown and assassinated in 1530. Nuño de Guzmán is depicted in the prehispanic manuscript known as the History of Tlaxcala. (Manuel de Ylláñez / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Fall of the Purépecha Empire

The two were on good enough terms that when the Aztecs were attacked by the Spanish in 1519 the Aztecs sent word to the Purépecha asking for help. They were ignored. The Purépecha wanted to wait and see who would come out on top. As the old saying goes – the enemy of my enemy is my friend. At least for a while.

After hearing about the Aztec’s defeat, the Purépecha tried to play nice and their ruler, Tangáxuan II, sent emissaries to the Spaniards. They soon returned to Tzintzuntzan with Spanish guests and the two sides exchanged gifts. Unfortunately, some of the gifts given by the Purépecha were gold and it’s easy to guess what happened next.

In 1522 the Spanish army, led by Cristóbal de Olid, arrived at Tangáxuan II’s doorstep. At this point, the Purépecha’s army was likely around 100,000 strong, more than powerful to give the Spanish trouble, but their leader made a surprising decision.

Rather than fight, he submitted to the Spanish, avoiding massive bloodshed. In return he was given a surprising level of autonomy and the Purépecha empire became a vassal state that paid tribute to the Spanish.

The Fall of Tenochtitlan – Truly the End of the Aztec Empire?

Will Pope Apologize to Mexico for Church Complicity during Spanish Conquest?

In truth, Tangáxuan II was trying to have his cake and eat it at the same time. While appearing to concede control of Michoacán to the Spanish, he covertly maintained his position as the true ruler. Despite allowing the Spanish to believe they held sway, he cleverly retained the lion’s share of tributes from his followers, forwarding only a fraction of these resources to the Spanish.

When the Spanish found out they’d essentially been tricked they were livid and sent the ruthless conquistador Nuño de Guzmán to set things straight. He found a Purépecha noble he could work with, Don Pedro Panza Cuinierángari, and the king was overthrown and executed on February 14, 1530. The next few decades saw much bloodshed as puppet leaders were repeatedly installed by the Spanish to try and keep the Purépecha under control.

Eventually under the softer approach of Bishop Vasco de Quiroga, Guzman’s replacement, things calmed down and the locals eventually stopped resisting Spanish occupation. This was largely thanks to the way Bishop Vasco de Quiroga earned the respect of many locals by advocating for the rights of the indigenous population and implementing policies aimed at improving their living conditions.

The Fuente de Las Tarascas, or the Tarascan Fountain, in Morelia, represents three of the most important princesses of the Purepecha culture: Atzimba, Tzetzangari and Erendira. “Tarascan” is a term referring to the Purépecha often considered derogatory. (Salvador Cervantes H / Adobe Stock)

The Legacy of the Purépecha Empire

The Purépecha empire, with its capital at Tzintzuntzan, was a significant Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in Michoacán. The empire, known for its distinctive architecture and advanced social organization, faced a transformative and ultimately tragic end with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the early 16th century.

Led by figures like Nuño de Guzmán and Antonio de Mendoza, the Spanish conquest dismantled the indigenous political structures. Despite the empire’s demise, the legacy of the Purépecha endures in archaeological wonders like Tzintzuntzan. Sadly, while they initially succeeded in resisting Spanish colonialism eventually the Purépecha empire fell, just like its powerful neighbors. While the historical record fondly remembers Bishop Vasco de Quiroga as a benevolent colonizer, the modern-day treatment of the Purépecha indigenous group reminds us of colonialisms dark legacy