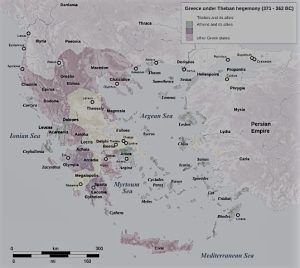

The Background of Ancient Greek History, 460 B.C.

The Historical Background of Ancient Greece 460 B.C.

Ancient Greece made significant contributions to the development of what is now known as contemporary European culture. She is located in the southeast of Europe, and the Aegean Sea divides her from Asia Minor.

Islands may be seen on the main peninsula’s three sides. Crete is one of the larger islands that can be seen directly beneath the peninsula. The Aegean culture, a significant civilization that predates the Ancient Greeks, was founded here.

Other names for the Aegean culture are Cretan and Minoan. The Aegeans or Cretans prospered as traders and established an empire long before the Phoenicians arrived as sailors and traders in this area.

On the Greek mainland, on the Aegean islands, and in Asia Minor, they constructed cities. The city of Troy served as their principal foothold in Asia Minor.

Ancient Greece 460 B.C

Between 2500 and 1400 B.C., the Aegean empire was at its height, with Cnossus most likely serving as its capital. King Minos’ magnificent mansion was discovered near Cnossus.

Probably as a result of the devastating eruption of the volcanic island of Thera, the Aegean civilisation on the island of Crete was devastated. Later on, the Mycenaeans from the mainland invaded Crete and overthrew the Minoans.

Greece’s ancient geography’s influence

Greece’s mainland is covered in rough mountains. The mainland is divided into numerous valleys by its crisscrossing hills. Tribes from Greece moved into these valleys. On the few farms, the vast majority of people worked as farmers, while the remainder took care of their cattle.

They greatly absorbed Minoan civilization and replaced the destroyed towns with new ones. The geographical obstacles prevented the Greek tribes from uniting as one nation. As a result, a number of little Greek city-states grew.

Development of City-states: The development of city-states was mostly caused by or aided by geographic circumstances and the early Greeks’ tribal nature. The valleys that each tribe lived in were divided from one another by mountains and rivers. And tribal devotion was strong enough to keep them apart on top of that.

The unification of all the Greeks was barely feasible under such conditions. Each city-state also fiercely defended its independence and frequently harboured jealousies of its neighbours.

A city-state with its own countryside established its own monarch and council-based government. Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Antigone were among the most significant city-states.

Ancient Greece Government Structures

All of the states had monarchies at first. With the aid of a council made up of nobles, each monarch started to rule his city-state. But for a variety of reasons, monarchy did not continue to be a widely accepted form of government. Particularly with relation to Sparta and Athens, there were alterations.

Probably the largest city-state was Sparta. Peers, freemen, and helots were the three social classes in this civilization. Only the peers received full citizenship; the others were left without rights. The peers acquired military training and maintained their readiness to put down the helots’ uprisings because the helots were constantly in uprising.

Athenian Democracy: Athens made significant advancements in politics, laws, literature, art, science, and philosophy in contrast to Sparta. Political experimentation was a favourite pastime in Athens. They rejected monarchy and oligarchy because they did not fit with their character. Democracy was finally ushered in.

It was the result of the efforts of Draco, Solon, and Cleisthenes, three enlightened law-givers. A clever aristocrat named Draco (621 B.C.) took the first step toward democracy by providing the Athenians with a written system of laws.

Cleisthenes: The lack of voting rights and access to public posts, however, made the situation of the average person worse. The tyrants took advantage of this circumstance and governed Athens for roughly fifty years. Despite their improvements, they lost favour and were forced to go. By awarding citizenship rights to male adults based on residence in a certain area, Cleisthenes, a member of the powerful Alcmaeonidae family, undermined the authority of the four original tribes’ governing clans.

The Persian Threat: The Persians established a sizable empire under the direction of Emperor Cyrus, whose boundaries extended from the Aegean coast in the west to the border of Afghanistan in the east. The Persians under Cyrus destroyed Croesus, the richest king in history and ruler of Lydia, in 546 B.C., opening the door for further development. The Persian emperors took control of the Greek cities in Asia Minor.

Revolt of Ionian Greeks: The Ionian Greek inhabitants of the towns of Asia Minor were enraged by the loss of their freedom and rose up in revolt (499–494 B.C.) against their Persian overlords, turning to the Greek cities on the mainland for support. A few other states, including Athens, offered aid. However, Darius the Great, the new Persian emperor, put an end to these uprisings and moved his focus to Greece. He sent aid to his disobedient Greek subjects in order to teach Athens a lesson.

Boxer Athlete Throwing a Discus an Ancient Greece

Persian Wars: The Persian ruler dispatched a sizable army to assault Athens, outnumbering the Athenian troops. At Marathon (490 B.C. ), the gallant Athenians engaged the Persians in combat, and they fought so valiantly that the Persians were forced to retreat. The Athenians lost 200 of their valiant men while the Persians sustained significant losses (6400 dead). The jubilant Athenian leader immediately despatched a runner home to tell his people about the magnificent triumph.

Battle of Thermopylae and Others (480 B.C.): The Marathon fight did not put an end to the Persian war. Darius’s successor, Xerxes, made the decision to exact revenge on the Persians ten years later. Taking the initiative himself, he planned land and marine missions to overthrow the Greeks. In Sicily and Italy, he encouraged the Phoenicians to assault Greek settlements. The threat to their survival became clear to the Spartans. Leonidas, her king, and 300 valiant men defended the Thermopylae pass for over three days until being betrayed. They were defeated by the last valiantly battling man. The Persian army invaded the fields of Athens after getting through this barrier. They advanced on Athens and set the city on fire.

The Golden Age: Pericles was Cleisthenes’ great-grandson. He led his forces to victory in the battles of Salamis and Mycale. He was educated by the most esteemed professors of the day because he was raised like an aristocracy. The Athenians were so confident in him that they elected him to the highest office (Strategos) for the ensuing thirty years. He was the one who completed putting the democratic system in place. As a radical politician, he favoured changes. The political power once held by the Arcopagus was transferred to the Council of Five Hundred.

Athens Rebuilt as the Most Beautiful City: Athens was completely wiped out during the Persian War. Rebuilding the city was the task that Pericles undertook. Large public buildings were built with the help of hundreds of artists and architects. The Parthenon on the Acropolis was the new city’s most alluring feature. The Parthenon was the most exquisite temple made of coloured marble ever constructed. The large marble statue of Athena, the city’s patron goddess, stood inside the temple.

Greek Philosophers of the Age of Pericles

The great Greek philosophers were interested in discovering or seeking the truth “about man and the universe.” They weren’t willing to accept anything that couldn’t stand up to the test of logic. The Era of Pericles was often referred to as “the age of reason.”

The greatest of them all was the Athenian philosopher Socrates (469–399 B.C. ), who advised his students to rigorously test any belief before accepting it. He made an effort to dispel his students’ various preconceptions through probing questioning and lively debates.

The Athenian authority saw his thoughts about Greek religion as subversive and corrupting the youth, finding him guilty, putting him to death. Plato, a brilliant philosopher, was one of Socrates’ students (427-347 B.C.). The lessons from his mentor are contained in his dialogues.

The Republic, Plato’s best book, envisions an ideal state ruled by a philosopher-king. Aristotle attended the academy that Plato established to instruct students. The latter is regarded by many as being among the greatest philosophers in history.

Greek Education in Antiquity

Sophists, or wise men or teachers, attracted a lot of attention from the younger generation who were more educated. Grammar, literature, astronomy, algebra, and oratory were all subjects they taught. All schools must now provide military training.

Literature from Ancient Greece

Greek dramas were at their peak during the Periclean era. The tragic plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were popular among the ancient Greeks. The best dramatist received an annual award from the Attic government following a public competition.

The three plays mentioned above that drew in all of Athens’ residents were among the most popular. It was well known that Aristophanes wrote comedic plays. Greeks have long been inspired by Homer’s epic writings.

Myths, stories, and folklore helped to popularise historical knowledge. But people have long questioned its veracity. Herodotus, who lived from 484 to 425 B.C., elevated history to its current prominence as “the father of History.”

He is renowned for giving a fascinating description of both his travels in the Near East and the Persian Wars. Thucydides, an additional Athenean who lived from 471 to 400 B.C., published the earliest history of science. His study of the Peloponnesian War, or the major conflict between Sparta and Athens, was his most significant contribution.

Ancient Greek Science Reframed

The Periclean era gave rise to brilliant scientists like Hippocrates and Anaxagoras. Hippocrates (460–377 B.C.) set the groundwork for modern medicine’s scientific approach.

In contrast to popular belief at the time, he “explained that ailments are of natural origin” and not brought on by evil spirits. He became a role model for other doctors in his era.

He created an oath that would require new medical professionals to uphold a set of moral standards (even now administered at the graduation ceremony). Great philosopher and geometrician Anaxagoras lectured in Athens between the years of 503 and 428 B.C. In 460 B.C., Democritus presented his atomic theory.

The world is very grateful to the Greek scientists for their significant contributions to science. In light of this, it is not surprising that historians have referred to Athens as “the School of Hellas.”

Greek City-States are Vanishing

The Delian League’s chief architect, Athens, amassed an empire at the cost of its other members. A few members of the Delian League wanted to leave when the Persian threat appeared to be over. However, Athens asked them to remain paying tribute to her and forbade them from leaving. People started arguing among themselves.

The Peloponnesian War—a conflict between Sparta and Athens that was inevitably brought about by Sparta’s intense jealousy of Athens’ rising dominance. Persia, which was constantly looking for ways to split up the Greek city-states, was helpful to Sparta.

After the infamous Battle of Aegospotami in 404 B.C., the conflict came to a close with Sparta ruling and Athens being defeated. For a while, the Greek city-states were in charge, but by the middle of the 4th century B.C., they were all still utterly divided.

Philip, king of Macedonia

King Philip of Macedonia invaded by using the division among the Greek city-states as an excuse. All of the Greek city-states, with the exception of Sparta, were subjugated by him. He came up with a strategy to confront the Persian empire as one Greek nation. He was slain before he could put this plan into action.

Ancient Greece’s legendary ruler Alexander

In the year 336 B.C., he was replaced by his 20-year-old son, Alexander the Great. Alexander was fortunate to inherit an extremely disciplined and skilled Greek army from his father. He had received instruction from none other than Aristotle the philosopher. Like his father, Alexander cherished Greek culture. Soon after he ascended to the throne, his own realm saw a mutiny.

Alexander brutally destroyed it. The Greeks were threatened and revolted since they believed Alexander was just a young kid, but he ruthlessly put an end to the uprising and completely destroyed Thebes.

Because Alexander respected the outstanding writings of the renowned poet Pindar, he spared his home. Greece was led by Alexander, who established himself as its unquestioned ruler, as they prepared to take on the Persian Empire.

In three separate engagements at Granicus (334 B.C. ), Issus (333 n.C.), and Arabela, he led a sizable Greek force of 35,000 warriors against the Persian Empire (331 B.c.). He ruled over the Phoenician cities as well as Egypt